By Jacob Wolinsky. Originally published at ValueWalk.

MPE Capital letter to investors for the year ended December 31, 2020.

Q3 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

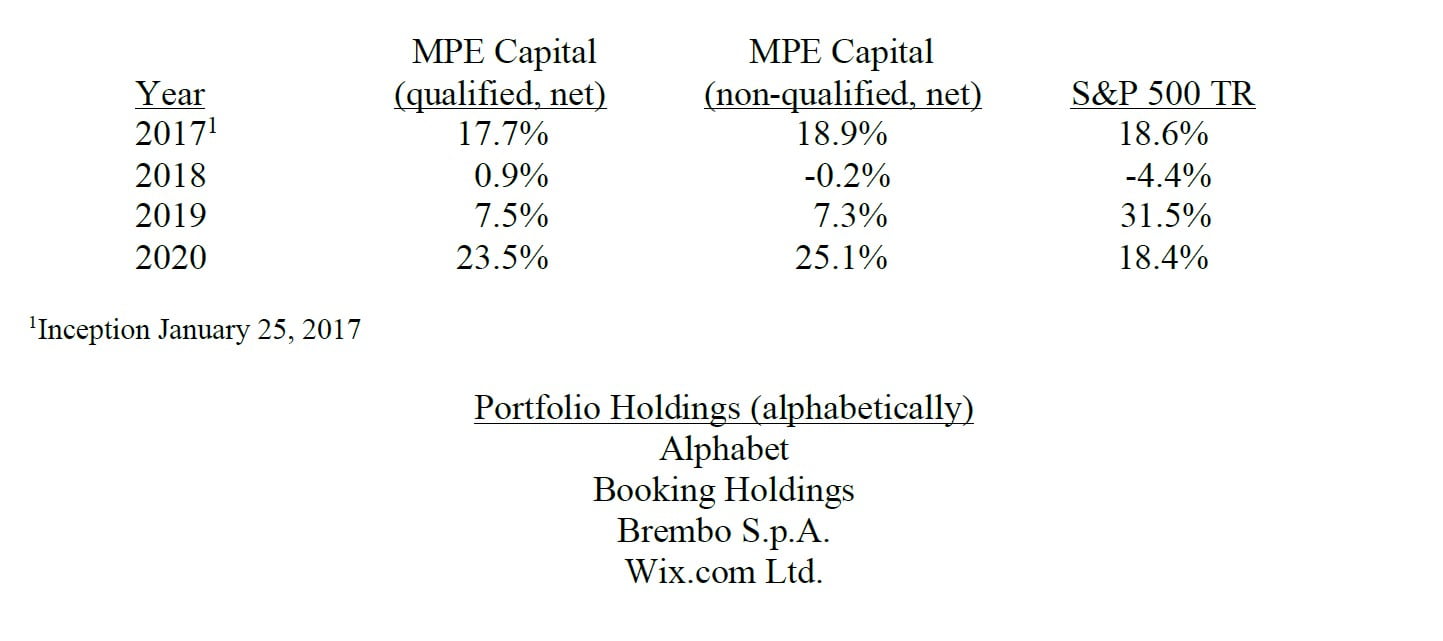

MPE Capital Performance

For the year ended December 31st, 2020, MPE Capital generated net returns of 25.1% for nonqualified clients and 23.5% for qualified clients. For comparison, the S&P 500 TR gained 18.4% during that same time period.

2020 marks the first recession MPE Capital has endured during its existence. Recessions are guaranteed to happen from time to time, and it may very well be that the next one will last much longer than this one did. Many investors are looking for investments that just go up in a straight consistent fashion. I think this is a fallacy and such line of thinking is harmful to expectational long-term results. Over the long run stock prices will follow business performance, but over the short run anything goes. To benefit from some of the best investments in history, you would have had to endure many periods of greater than 50% declines (peak-to-trough).

Using Amazon as an example, let’s say you knew that from day one it would be a terrific investment (extremely unlikely). Had you invested $10,000 in 1997 when they completed their initial public offering (IPO), today you would have about $18 million (over 37% per annum). During that twenty-three year or so period, you would have experienced some serious short-term declines along the way. In the early 2000’s, the stock price fell about 95% peak-to-trough. It also fell about 65% peak-to-trough during the global financial crisis in 2008. You also would have experienced numerous 30% plus declines, with the most recent one being in 2018.

The above example is a great reason why short-term investment performance really means nothing. Day to day, quarter to quarter, and even yearly results are generally just noise. However, over the long run (say five years plus), as long as the businesses we own continue to prosper, their stock prices and our investments, if purchased at reasonable valuations, will do just fine.

Recap Of 2020

Nobody went into 2020 anticipating what was going to unfold. The S&P 500 declined by over 35% peak-to-trough, the unemployment rate hit nearly 15%, and a projected one in six restaurants will face permanent closure. The list can go on and on, and I’m not even going to mention the tragic loss of nearly two million lives due to this terrible virus. I hope you and your loved ones are all doing well and staying safe.

Despite all the bad news, our portfolio holdings are doing fine. All of them have ample liquidity and will make it through this recession just fine. We were also fortunate to have substantial cash holdings going into the recession, giving us the ability to purchase a few new investments at bargain prices.

Contrary to popular belief, recessions are actually good things. They rid the economy of fragile businesses that probably shouldn’t be allowed to get too large. They result in new innovations that otherwise wouldn’t have occurred (think Airbnb during the global financial crisis). In a way, a recession is like a fast or a reset button for the economy. It purges away all the weak businesses (autophagy) and creates a more stable base going forward.

The most common mistake investors make during these economic resets is to panic. They panic and sell to cash, fearing the situation will only get worse. Sometimes they just want to wait for things to look more optimistic before they repurchase shares. Unfortunately, most investors tend to sell at the absolute worst time, generally at market bottoms. They then chase the market on the way up, missing out on sizeable gains due to emotional decision making.

I’m very fortunate that not a single client of MPE Capital panicked during the market declines of this year, most notably during March. Stock market prices don’t give us any information about the value of our holdings. I perform deep due diligence in order to estimate a fair price for every investment we own and will make. The only time the stock market price is important is if we are looking to buy or sell. If the market price is far below any conservative level-headed estimate of fair business value, we can take advantage by purchasing more shares. Conversely, if the market price is far above, we may sell some of our shares.

During March of this year, the market served up some serious bargains. When talking to one of my close friends and client, I compared the situation to a poker game. Imagine sitting at a poker table playing against some very tough opponents, at best over the course of a few hours you will win a few chips. However, when March rolled around, it was akin to a group of very wealthy heavily intoxicated businessmen (whales) sitting down at your table. As a more seasoned poker player at the table—you will begin to salivate (hopefully not so much so that you scare off the whales).

Sell Discipline

I’ve spent a lot of time recently thinking deeply about when to sell an investment. The more obvious reasons are (1) deteriorating business fundamentals, (2) value destructive behavior by management, (3) realizing the investment was a mistake, and (4) identifying a relatively superior investment opportunity. However, what if none of the above criteria are met? What if the business is still maintaining its competitive advantage and management is competent? What if the only factor is that the stock price is in excess of a fair estimate of intrinsic value?

Thinking about those questions, led me to consider this scenario: Imagine selling Berkshire Hathaway or Wal-Mart in the early days and missing out on the subsequent multi-decade compounding of business value. That would be a terrible mistake of omission.

However, I also want to avoid the Coca-Colas of the late 1990s, where an investment including the reinvestment of dividends returned just 0.37% per annum from July 1998 to December 2007 (peak-to-peak over a period of about ten years). Even fast forwarding to 2020, you would have earned only about 5% per annum from July 1998 (a holding period of over twenty years).

So, what’s the solution? How to avoid the Coca-Colas of 1998 but not miss out on the Wal-Marts of the 1980s? I think something critical to take into consideration is the size of a business relative to its total addressable market. In the case of Coca-Cola, the most important question was how many servings per day will they sell once mature, compared to how many servings per day they were selling at the time.

In general, I think it’s a mistake to sell a business with lots of future growth prospects just because the current market price is slightly ahead of its fundamentals. Conversely, I think it’s also a mistake not to sell a mature or nearly mature business if the market is pricing in earlystage high-tech company growth rates.

For the full year 1998, Coca-Cola sold about 200 billion servings or about 0.55 billion servings per day. In the ten years prior to 1998, servings grew about 6% annually and revenues grew about 8.5% annually. Once mature, servings should grow in line with population growth and revenues a little higher due to pricing power, let’s say about a 3% revenue growth per annum upon maturity. Taking into account they had already expanded internationally; it would be hard to imagine the business growing faster in the ten years following 1998 as compared to the prior ten years.

Taking the above into consideration—with the enormous benefits of twenty-twenty hindsight— we could forecast something along the lines of mid-single digit growth for Coca-Cola in 1998. This would be a sign that the business is far closer to maturity and its high-growth phase is probably coming to an end. Had we compared our estimates of intrinsic value in 1998 with the market price, we probably would have seen a huge disconnect. The market was pricing in far more optimistic prospects for Coke at the time; however, had our forecasts been correct, the future returns were bound to be subpar at best.

Now, let’s take a look at Wal-Mart in 1982, ten years after their initial public offering. They were generating net sales of about $2.4 billion across 491 stores in thirteen states. It wasn’t unfathomable to assume that their everyday low pricing business model (EDLP) was a huge success, and that they could easily expand across all fifty states. Fast forward to today and they have 11,500 stores across the globe and generate over $0.5 trillion in sales (up over 200x from 1982 or about 15% per annum).

In addition to the total addressable market mental model mentioned above, I also find it helpful to estimate forward five or ten year returns relative to the current market prices of our holdings. For example, if we purchase a business that I think we can sell for 6x in ten years, we will earn about 20% per annum. If that same business after year one increases in price to 4x, we will earn only about 4.6% per annum over the next nine years. If I think over the next nine years I can find an idea that will do better than 4.6% per annum, I should theoretically sell and redeploy that capital into a more favorable investment opportunity.

One inherent flaw with the above approach is that the future is always going to be uncertain. Some businesses will inadvertently stumble upon an AWS-esque1 idea that will end up boosting their future intrinsic value by a decent magnitude. Therefore, I think it only makes sense to pursue the above approach if I can be reasonably certain that the future business model and operating segments will look quite similar to the present (e.g. Coca-Cola in 2007 versus 1998). Even in the case of Wal-Mart, if the market price in 1982 reflected 20x the net sales at the time, it might make sense to sell and wait to redeploy that capital into a more favorable investment opportunity.

In conclusion, if I were to offer a heuristic or rule of thumb (everybody loves a heuristic), I would say in general it is a mistake to sell to cash, assuming none of the original four criteria are met. Ideally, I will always be selling one investment to purchase another of higher relative quality, larger relative discount to intrinsic value, or a combination of the two.

Portfolio Updates

As I mentioned in the first-half letter, we made a few new investments during the year. I discussed two of those new holdings in the previous letter (Wix and Brembo). I also made some sizeable additions to previous holdings as the market offered us deep discounts to my estimates of fair value.

One notable example being Booking Holdings. During the depths of the market panic of March, the market price reflected a half-off deal (very conservatively valued) for a well-capitalized leading accommodation travel platform run by a talented CEO. Booking Holdings had and continues to have plenty of cash on their balance sheet, a highly variable cost structure where they can shut-off advertising spend to save tons of cash (advertising was 33% of revenues in 2019), and a leading accommodations platform with deep network effects predominantly amongst independent hotel operators in Europe. There are risks that business travel may never recover to pre-covid peaks, but I don’t think leisure travel will follow that same lead—Google Images is a poor replacement for seeing the Palace of Versailles in person.

We ended up selling two large holdings throughout the year for decent gains. This unfortunately leaves us with a sizeable cash position. As I’ve stated in previous letters, I detest holding cash. Cash is a guaranteed losing investment with short-term interest rates near zero percent and inflation at two percent. Hopefully with some good old-fashioned elbow grease, I hope to uncover a few undervalued businesses to put our cash to good use.

Concluding Thoughts

It has been a wild year, and I am very grateful to have such wonderful investors who are longterm oriented and allow me to manage MPE Capital the same way as if I was just managing my own capital. I am pleased with our outperformance this year, but I am more so focused on our five and ten-year results (both absolute and relative to the averages).

I have learned a lot over the last few years, and I hope with my newfound knowledge we will enjoy very favorable returns going forward. Unfortunately, I haven’t uncovered any attractively priced opportunities recently, but I will continue going into work every day with the objective of allocating our cash into some mouthwatering investment opportunities.

I wish you all a terrific and safe 2021. Hopefully we can put this pandemic behind us soon enough and return back to a modicum of a normal life.

Sincerely,

Michael P. Ershaghi

The post MPE Capital 2020 Full-Year Letter: The Importance Of Sell Discipline appeared first on ValueWalk.

Sign up for ValueWalk’s free newsletter here.