Courtesy of The Automatic Earth.

Arnold Genthe Long Beach, New York Summer 1927

Oh yay, US Q2 GDP supposedly rose by 4%. Aw, come on. That’s only 7% more than in Q1 (or 6.1% in the once again revised Q1 number). Wonder what made that happen? Don’t bother. It’s complete nonsense. New home sales and lending home sales went down – again – recently, wages are not going anywhere, the ADP jobs report was – again – low today. There’s nothing that adds up to a 6% or 7% difference between Q1 and Q2.

The real story of the American economy lies elsewhere. The economy is sinking away in a debt quagmire. If it were a body, the economy would be in up to its neck in debt by now, with the head tilted backwards so it can still breathe. Barely. But your government doesn’t want you to know. There are a lot of things that illustrate this.

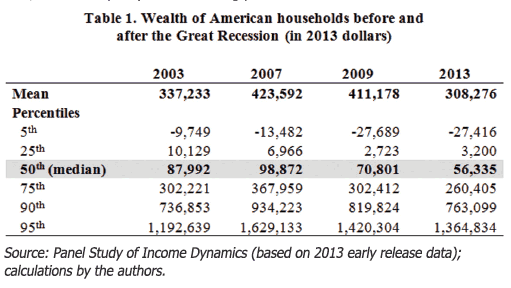

First , let’s go back a few days to the Russell Sage Foundation report, Wealth Levels, Wealth Inequality And The Great Recession, that I mentioned in Washington Thinks Americans Are Fools. I posted a pic from the report and said it “makes clear ‘recovery’ is about the worst possible and least applicable term to use to describe what is happening in the US economy”:

Households at the “median point in the wealth distribution – the level at which there are an equal number of households whose worth is higher and lower”, saw their wealth plummet -36% from 2003 to 2013. From the highest point, in 2007, to 2013 the number is -43%. Five years after 2008 and Lehman, five years into the alleged recovery, which raised US federal, Federal Reserve, and hence taxpayer, obligations by $10-$15 trillion or more, US median household wealth was down -36% from 2003. And that’s by no means the worst of it:

If you look at the 5th and 25th percentile ‘wealth’ numbers (much of it negative), you see that they went down from 2003 to 2007, while the median was still rising. For both, wealth in the 2003-2013 timeframe deteriorated by some -200% (or two-thirds, if you will). -$9,479 to -$27,416 for the poorest 5%, $10.219 to $3,2000 for the lowest 25%.

What I didn’t do was add up the numbers, and though when you’re using ‘median’ or ‘typical’, it’s hard to be sure about those numbers, we can derive some things from it that won’t be too far off. The -36% loss suffered between 2003 and 2013 by the ‘typical household’, which lowered the inflation-adjusted net worth from $87,992 to $56,335 (a loss of $31,657 per household), meant, assuming 120 million US households, that some $3.8 trillion in wealth went up in air. Because wealth (though partially virtual) went up from 2003 to 2007, the loss between 2007 and 2013 was larger: at $42.537 per household, the total loss came to $5.1 trillion. And don’t forget, that happened during the so-called ‘recovery’.

It should surprise no-one, therefore, that a report issued by the Urban Institute and the Consumer Credit Research Institute states that over a third of Americans in 2013 had debt in collection (i.e. reported to a major credit bureau). WaPo’s take:

A Third Of Americans With Credit Files Had Debts In Collections in 2013

About 77 million Americans have a debt in collections, a new report finds. That amounts to 35% of consumers with credit files or data reported to a major credit bureau, according to the study released Tuesday by the Urban Institute and Encore Capital Group’s Consumer Credit Research Institute. “It’s a stunning number,” said Caroline Ratcliffe, senior fellow at the Urban Institute and author of the report. “And it threads through nearly all communities.” The report analyzed 2013 credit data from TransUnion to calculate how many Americans were falling behind on their bills. It looked at how many people had non-mortgage bills, such as credit card bills, child support payments and medical bills, that are so past due that the account has since been closed and placed in collections.

Researchers relied on a random sample of 7 million people with data reported to the credit bureaus in 2013 to estimate what share of the 220 million Americans with credit files have debts in collection. About 22 million low-income adults who did not have credit files were not represented in the study. This is the first time the Urban Institute calculated the collection figure, but Americans may have been struggling with debt for a while: Researchers noted that the 35% is basically unchanged from when the Federal Reserve studied the issue in 2004 and found that 36.5% of people with credit reports had debt in collections. The debts sent to collections ranged from $25 on the low end and to more than $125,000 on the high end. [..]

… not all consumers get hassled: some people may not even learn they’ve been sent to collections until they check their credit reports, the study noted. That doesn’t mean the debts didn’t cause any setbacks. Bills that are sent to collections can stay on a person’s credit report for up to seven years, hurting a consumer’s credit score and in turn hindering their chances of accessing loans, credit cards and other forms of borrowing. A bad credit score can also hurt a person’s ability to land a job or their odds of getting approved for an apartment [..]

Note that not all debt is included, and perhaps quite a lot is not: in the gutters of America, there are for instance 22 million low-income Americans who don’t even have a credit file. They are most likely to use things like payday loans, which are also not included. But there is more slipping through the reporting cracks, as I noticed the end of the WaPo piece unveils, just like Tyler Durden did:

Deadbeat Nation: A Shocking 77 Million Americans Face Debt Collectors

But how is it possible that tens of millions of Americans are in such dire straits? After all, banks have been reporting better delinquency data for years. The answer: the study found that the share of people with debt past due, meaning they are at least 30 days late with payment on a non-mortgage debt, was much smaller: 1 in 20 people. That includes people who are late with credit card bills, student loan payments and auto loans. The majority of those people, 79%, also had debt in collections. However, because certain bills, such as medical bills and parking tickets, may not show up on a person’s credit score until they are sent to collections, the total share of people falling behind on their bills may actually be much higher.

… the stunner is that the share of Americans with debt in collections is 7 times greater than those with merely debt past due …

I’ll add something else: since only 220 million of the 320 million Americans have a credit file, it’s safe to assume that if you add dependents, children, close to 120 million Americans, perhaps even more (an average of one for every household), live in a household that has debt so far past due that debt collectors have been notified. In other words, not just debt, but bad debt.

AP points out the link to the jobs market and wages:

The Urban Institute’s Ratcliffe said that stagnant incomes are key to why some parts of the country are struggling to repay their debt. Wages have barely kept up with [rising prices] during the five-year recovery, according to Labor Department figures. And a separate measure by Wells Fargo found that after-tax income fell for the bottom 20% of earners during the same period.

But what I find more interesting is the positive twist USA Today manages to give to the story (just when you thought all was lost, here comes the cavalry):

A Third Of Americans Delinquent On Debt

When it comes to overall debt levels, most comes from mortgages, which make up 70%, on average, of Americans’ debt load. Wealthier states tend to have the highest amount of debt and percentage of debt held in mortgages, but the researchers point out that Americans with higher debt may also have higher incomes and better access to credit.

Isn’t that just a swell trick? The report the paper comments on is about the 77 million Americans who have debt in collection, but before you know it they switch to overall debt, and insinuate that because a lot of it is in mortgages, things are not that bad. And the trick gets better, even one of the report’s authors gets sucked in:

“Total debt really mimics mortgage debt,” says Caroline Ratcliffe, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute and one of the authors of the report. Ratcliffe classifies mortgage debt as what’s generally considered “productive debt.” “We talk about credit and access to credit as a good thing, but debt as a bad thing,” she says. “Access to credit can result in productive debt that moves us forward.”

I read somewhere the past week that credit is, in principal, good, and it’s the American way etc. And as we see here, mortgage debt is seen as productive, even by the report’s authors. But that’s not what the report was about!! (picture me shouting here).

I think that in today’s economy it’s a grave mistake to classify all mortgage debt as productive. I definitely see that as an idea of long lost times. After all, the same classification must have been used in 2007, but then right after a lot of that mortgage debt turned sour. It wasn’t so productive after all.

To see debt as productive, you have to have the expectation that it’s going to make money for the debtor. Or better yet, actually produce something of value. And to think that today’s mortgage debt will produce profits, you need the idea that home prices will rise.

But when you look at the wealth loss suffered by Americans as seen above, and you combine that with the huge rise in bad debt, where would you want to get that rise in home prices from? There’s only one place, isn’t there: more debt. And that trick won’t wash ad infinitum.

Classifying all of today’s mortgage debt as productive, de facto seeks not just to redefine the word productive, but to turn it on its head.

There’s one sector of the US economy that is going kind of strong: car sales. But why do you think that is? That’s right: debt. Is car debt classified as productive too, perhaps? Bloomberg:

Is Your Car an Underwater Time Bomb?

Even as job and wage growth have stagnated, auto sales have uncoupled themselves from those traditional economic drivers to become one of the few sources of strength in the macroeconomic picture. As the economists Amir Sufi and Atif Mian point out in their new book “House of Debt,” one of the big factors supporting overall retail spending in the U.S. since 2008 has been the expansion of auto credit. Sufi and Mian don’t celebrate this fact – they rightly see it as a symptom of broader secular stagnation in the U.S. economy. Indeed, a few recent statistics demonstrate the very precarious underpinnings of the auto industry’s prosperity:

- The average auto-loan term has increased every year since 2010, reaching 66 months in the first quarter of this year, according to Experian Automotive. In the same period, loans with terms of 73 to 84 months grew 28%, while loans with terms from 25 to 72 months actually fell.

- Equifax reports that U.S. auto loan volumes are at an all-time high, with some $902.2 billion outstanding at the end of the first half of 2014, up 10% year-over-year.

- The New York Times reports that subprime auto loans have grown by 130% in the last five years, with subprime lending penetration reaching 25% last year.

- Leases make up another quarter or so of auto “retail sales” according to Experian, another metric that is currently at all-time highs.

- 27% of trade-ins on new vehicle purchases in Q1 2014 had negative equity, according to the Power Information Network, another troubling indicator on the rise in recent years.

With half of new car sales supported either by leases or subprime credit, and ballooning loan terms leaving an increasing number of new car buyers underwater on their trade-ins, it’s clear that auto demand is hardly at a sustainable, organic level. Last year, 38.8% of dealer profits came from financing operations, according to the National Automobile Dealers Association, and General Motors has relied on some $30 billion in largely subprime receivables held by its GM Financial unit to show an increase in revenue in the first two quarters of this year.

The only thing that keeps the American economy from collapsing outright and face first in this debt crisis is more debt. And it’s not just America: China, Japan, UK, they’re all on the same path, while Europe, once deflation sets in, will have to follow suit or break into smithereens.

And what should make me believe that Putin has not already had his economic team figure out a sweet spot for gas delivery to Europe, where he can reduce volume and let the Europeans fight amongst themselves over what’s left, and at the same time still keep his profits rising?

With a 4% official GDP number, the Fed has no choice but to keep up the taper. And I don’t think it would even want to have that choice. In the current geopolitical environment, which the US has largely created all by itself, making fewer dollars available in global markets can work wonders for the American dreams of empire.

The amount of dollar-denominated debt emerging economies have ‘engaged’ in will in short order devastate many of them, Europe will have a very hard time, and Japan will sink into oblivion (and perhaps try to shoot its way out). The BRICS’ plans to start their own bank will only hasten US determination.

Yellen doesn’t have to make a decision to raise rates, all she has to do is taper and rates will rise by themselves. If she raises rates on top of that, it’ll be a matter of weeks or months for many nations, companies and individuals.

Higher rates will stab the global economy in the heart, including US citizens, but they will boost the – dreams of – empire. For a while. But then, as the sanctions on Russia, based on at best paper thin and at worst entirely fabricated allegations, make abundantly clear, we’ve entered a new age. The pie is shrinking, and ever more people are clamoring for the ever fewer pieces of that pie.

Debt can only carry us so far, and that’s not a huge distance either; the game stops when the combination of principal and interest payments grows over debtors’ heads, as many of you can attest to. The taper alone will cause many to reach that point of no return; it will push a billion people, or two, over the brink. Argentina’s default is but the first of many.

What’s more important now is that fossil fuels, too, have a limited ‘carrying capacity’. And the planet. It’s going to be all cats in a sack from here on in, with everyone jockeying for a handful of rotting, dwindling and crumbling musical chairs. A 4% US GDP print is but a sidenote in that; it merely serves to avert people’s eyes away from their real futures. But then, Americans are no longer used to looking at those anyway. They’re not exactly a people with a strong link to reality.