The People’s Republic of Debt

By John Mauldin, Thoughts from the Frontline

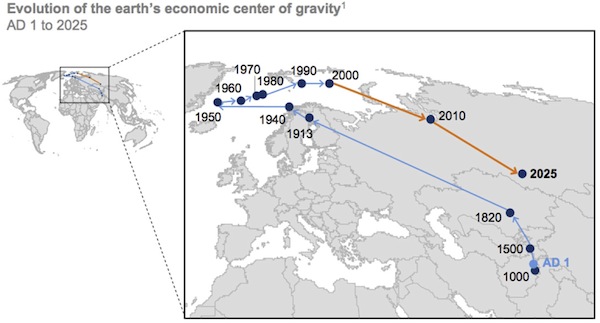

It wasn’t that many centuries ago that China was the absolute economic center of the world. That center gravitated to Europe and then towards North America and has now begun moving back to China. My colleague Jawad Mian provided this chart showing the evolution of Earth’s economic center of gravity from 2000 years ago to a few years and into the future:

Most investors are well aware of the enormous impact China has had on the modern world. Thirty-five years ago China’s was primarily an agrarian society, with much of the nation trapped in medieval technologies and living standards. Today 500 million people have moved from the country to the cities; and China’s urban infrastructure is, if not the best in the world, close to that standard.

The economic miracle that is China is unprecedented in human history. There has simply been nothing like it. Deng Xiaoping took control of the nation in the late ’70s and propelled it into the 21st century. But now the story is changing. Those who think that all progression is linear are in for a rude awakening if they are betting on China to unfold in the future as it has in the past.

Among the most important questions for all investors and businessmen is, how will China manage its future and the problems it faces? There are many problems, some of them monumental – and at the same time there is an amazing amount of opportunity and potential. Understanding the challenges and deciphering the likely outcomes is itself an immense challenge.

A Brand-New Book Available Online

My colleague Worth Wray and I have been investigating and writing about China for some time now. Today I’m announcing a book that we have written and edited in collaboration with 17 well-known experts on China. The book is called A Great Leap Forward? Making Sense of China’s Cooling Credit Boom, Technological Transformation, High Stakes Rebalancing, Geopolitical Rise, & Reserve Currency Dream, and we think it will help you to a solid understanding of both China’s problems and its opportunities. I know, the subtitle is a tad long, but the book does really cover all those aspects of today’s China.

Notice that there is a “?” after the title “A Great Leap Forward.” The first Great Leap Forward, initiated by Mao Tse-tung in the early ’60s, was an utter disaster. It devastated the nation, bankrupted the economy, and caused the deaths of tens of millions of people. Let’s review a little history from the introduction to the book:

When Chairman Mao decided in 1958 to transform China’s largely agrarian economy into a socialist paradise through rapid industrialization, collectivization, and a complete subjugation of the market to Chinese Communist Party (CCP) central planners, the widespread misallocation of resources led to the worst famine in recorded history and the outright collapse of China’s economy.

With very little capital at China’s disposal after its long civil war and even longer subjugation to foreign colonialists in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Mao decided the best way to fund the country’s rapid industrialization was for his government to monopolize agricultural production, use the nation’s bounty to support industrializing urban populations, and finance fixed-asset investments with crop exports.

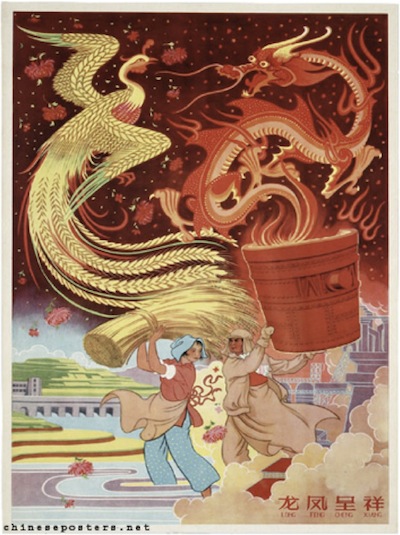

1959 –– “Prosperity brought by the dragon & the phoenix”

Seeing grain and steel production as the essential elements of China’s rapid development, Mao boasted in 1958 that China would produce more steel than the United Kingdom within fifteen years.

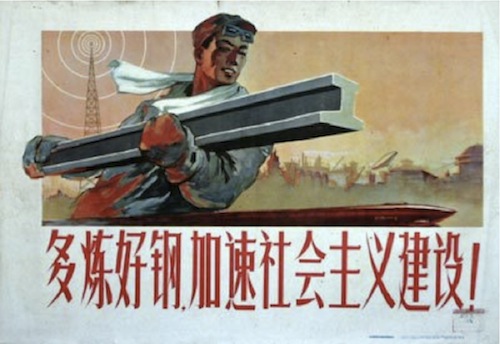

1959 –– “Smelt a lot of good steel and accelerate socialist construction.”

Mao had very limited knowledge of agriculture or industrial production, yet he ruled China with an iron fist and silenced even well-intentioned opposition. China’s rural peasants were forced into collectives; households were torn apart; and private property rights were completely abolished. Mao ordered agricultural collectives to produce more grain while forcing farmers to employ less productive methods; he mobilized farmers to kill off “pests” like mosquitos, rats, flies, and sparrows (a campaign that upset the ecological balance in China’s farmlands); and insisted on a doubling of steel production to be achieved by diverting farmers with no industrial skill into operating poorly supplied backyard furnaces (which could not burn hot enough to produce high-quality steel).

1959 – Unskilled workers smelt steel in China’s backyard furnaces.

Steel production surged, and the economy appeared to boom… but at least half of that new production was unusable. A proliferation of crop-eating locusts (after the sparrows had been killed off) and the diversion of farm workers to industrial and public works projects led to a collapse in crop yields. Still, local officials all over China falsified their production figures in an effort to win favor with Beijing (and to spare themselves Mao’s wrath), which led to larger and larger grain shipments to China’s cities… and smaller and smaller rations for those living in its agricultural collectives.

Instead of taking a Great Leap Forward to a harmonious industrial society…

1959 –– “The commune is like a gigantic dragon, production is noticeably awe-inspiring.”

Mao’s command-and-control system dismantled the Chinese economy, ruined millions of lives, and left an enormous share of China’s population disillusioned.

Industrialization failed. From 1958 to 1961, millions died of starvation and exhaustion across China’s countryside (independent estimates range from 30 million to 70 million, while the CCP still insists the death toll was only 17 million), and the People’s Republic remained a net exporter of grain. As Harvard economist Dwight Perkins remembers it, “Enormous amounts of investment produced only modest increases in production or none at all…. In short, the Great Leap was a very expensive disaster.

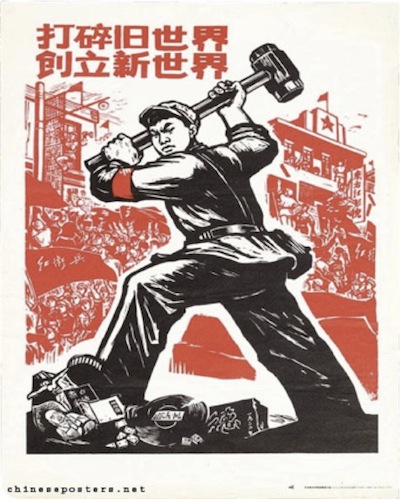

As production and productivity collapsed along with the CCP’s social contract, Mao struggled to retain power as a number of influential officials sought to implement more market-oriented policies in response to the Great Famine. Fearing that growing opposition could lead the Party to reject its Marxist spirit (as the Soviet Union had done under Nikita Khrushchev a decade earlier), in 1966 Mao and his Red Guards launched the Cultural Revolution – a decade-long series of purges intended to root out enemies of Communist thought lurking within the Party, cleanse Chinese society of many of its traditional values, eliminate elitist urban social structures, and renew the spirit of China’s Communist revolution.

1967 – “Scatter the old world, build a new world.”

Under Mao’s leadership, the Party destroyed cultural artifacts, banned the vast majority of books, dismantled the educational system, and silenced millions for thought crimes against the Party. In a devastating blow to China’s human capital, Mao ordered children of privileged urban families – including current President Xi Jinping, when his father, Xi Zhongxun, was purged – to relocate far away from their families to be re-educated through manual labor in China’s countryside. What may have been the most promising youth of that “Lost Generation” were deprived of their educations and forced into hardship.

1972 –– President Xi Jinping during the Cultural Revolution

Considering the legacy of the Great Leap Forward, the Great Chinese Famine, and the Cultural Revolution, it is an understatement to say that Mao’s hardline policies devastated the economy and left deep scars at all levels of Chinese society. After Mao’s death in 1976, it didn’t take long for the pragmatic Deng Xiaoping to win control of the Party and take China in a new economic direction –– though with essentially the same repressive political system.

And now young XI Jinping has come from experiencing the Cultural Revolution, getting ready to embark upon what we believe is something as equally as revolutionary as the first Great Leap Forward. The question mark is whether it will be another disaster or a decisive leap into a new future, perhaps even a new world order.

My friend Woody Brock reminds us in his latest PROFILE that the theory of growth in emerging markets dates from 1960, with the publication of Walt Whitman Rostow’s book The Stages of Economic Growth. Rostow gave us a description of five different stages that “mark the transformation of traditional, agricultural societies and modern, mass-consumption societies.”

The first three stages can be accomplished just as readily in a top-down economy as in a bottom-up economy, and there are historical reasons to believe a command economy might have some advantages. The tricky part is in the evolution from a society that is industrializing and building infrastructure into an economy that is consumer-driven and thus by definition must be bottom-up and entrepreneurial.

Command economies, with their crony capitalism and unequal rule of law, simply will not develop into full-fledged, economically successful nations. Further, there has to be both explicit and implicit permission for entrepreneurial achievements. Crony capitalism, which is a false capitalism, seeks to keep the profits from an economy in the hands of a small group. And that dynamic limits the growth of the overall economy. To achieve a full consumer society there must be open admission for everyone into the halls of business and private property ownership.

What Xi Jinping is attempting in China is no less revolutionary than what Deng Xiaoping did in 1980. In many ways it will be harder, because Deng was embarking on a phase in which a top-down economy might thrive. Xi has to change the very nature of the current system in spite of entrenched forces that do not want to give up their privileges.

There is reason to believe that Xi understands exactly what needs to be done. The question is, can he pull it off? If he does, China will for a time grow at a much slower rate, and the nature of its economic progress will shift. He understands that he cannot continue to grow the economy on debt forever. Or at least it appears that he does. One way to look at the current anticorruption effort is to see it as a way to demonstrate to deep-rooted crony capitalists that their time is at an end and that it’s time to figure out how to work in the new China that Xi is trying forcefully to pull the nation towards.

A number of our contributors to the book are optimistic about the potential for China to succeed. Others – the clear majority – see little hope. What we have tried to do in the book is give you a sense of all sides of the argument. For the optimists to be right we will need to see certain events unfold in a reasonably timely fashion. If they don’t, it will be time to take a more pessimistic view. We have tried to be evenhanded and open-minded in our selection of authors and topics. And while we have our own views, we have let our contributors present theirs as forcefully as possible.

I’m immensely proud of this book and believe it will become one of the definitive expositions on modern China. And it should be, considering the breadth and depth of the contributing authors, many of whom you will recognize and others whom you will be glad to have met. Take a glance at the list of contributing authors (in alphabetical order), all first-rate experts in their fields:

Andrew Batson, Ian Bremmer, Ernan Cui, Jason Daw, Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, Louis-Vincent Gave, David Goldman, Mark Hart, Neil Howe, Simon Hunt, George Magnus, Jawad Mian, Leland Miller, Raoul Pal, Michael Pettis, Sam Rines, Jack Rivkin, Nouriel Roubini, Gillem Tulloch, Logan Wright, and Wei Yao. Plus an introduction and editing by Worth Wray and your humble analyst.

The book is available (for now) only in an e-book format. You can get it on Amazon Kindle,iTunes Books, and Barnes & Noble Nook. If you want to know more about the book and the authors, you can go to this page on my website.

Amazingly, and thankfully, there have been a number of very positive reviews before we’ve even announced the book. (It has been live for a few days just to make sure that all the technology was working right.)

And one last detail. We have set the price of the book at $8.99. That is not a typo. If we tried to do the book in a print format, we would have to set the price closer to $50. There are at least 100 full-color graphs and charts in the entire book, and it would just not be the same to publish them in a black and white format. At the end of the letter, in my personal section, I will comment on the process of self-publishing an e-book and how one goes about marketing in this brave new Internet world. Some of you might find those thoughts interesting, but for now let’s look at a key section from the introduction to the book:

It’s no secret that China has a massive debt problem. Raoul Pal (Chapter 1: “There’s Something Wrong in Paradise”) warned back in 2003 that there was something amiss in China’s success story. Since that time, foreign capital chasing a bullish growth story and nervous central planners in Beijing acting to maintain rapid GDP growth post-2008 have conjoined to enable one of the largest credit booms in history.

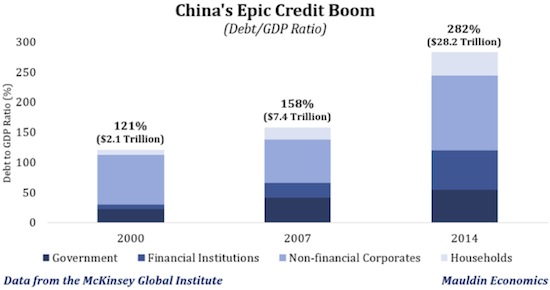

According a recent report from the McKinsey Global Institute, China’s total debt stock more than tripled between 2000 and 2007 and nearly quadrupled from 2007 to 2014 as private-sector and local-government borrowers added more than $26 trillion in new debt. That explosion in domestic credit lifted the country’s total debt-to-GDP ratio from 121% in 2000 to 158% in 2007 and to 282% by the end of 2014; and China’s $21 trillion in net new debt incurred between 2007 and 2014 accounted for more than 36% of the $57 trillion in cumulative global debt growth following the global financial crisis.

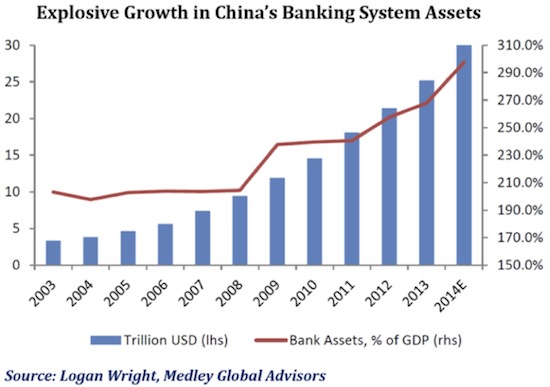

By another measure, the explosive growth in China’s financial system is literally unprecedented, with total assets (outstanding loans) standing around $27 trillion – or roughly one third of global GDP. According to Medley Global Advisors’ Logan Wright, China’s banking assets have grown by roughly $17 trillion since 2008, while nominal GDP has grown to $4 trillion. As Wright explains in Chapter 3 (“‘Deliquification’ & China’s Deflationary Adjustment”), “There are no available comparisons for a country adding around 20% of global GDP in new bank assets over such a short period; the Japanese banking system peaked at around 20% of global GDP in total assets.” And we know what happened in Japan.

Not only is this kind of credit boom unsustainable, it’s also inherently destabilizing. The harder and faster that credit growth runs, the higher the chance of broad-based misallocation, which eventually exerts a drag on economic activity just as powerful as the boost it provided in previous years, and sometimes moreso. As GMT Research’s Gillem Tulloch explains in Chapter 2 (“The Tyranny of Numbers”), “Bubbles start on the back of vast quantities of cheap credit, are fed by the creation of ever greater quantities of it, and collapse when the taps are turned off.”

To continue reading this article from Thoughts from the Frontline – a free weekly publication by John Mauldin, renowned financial expert, best-selling author, and Chairman of Mauldin Economics – please click here.