Courtesy of ZeroHedge. View original post here.

We warned previously that when (not if) the market crashes next, The Fed is going to need a scapegoat (other than British traders living at home with their parents) and judging by The Fed's Lael Brainard's comments today, high-frequency-traders (HFT) are in the crosshairs.

We warned previously that when (not if) the market crashes next, The Fed is going to need a scapegoat (other than British traders living at home with their parents) and judging by The Fed's Lael Brainard's comments today, high-frequency-traders (HFT) are in the crosshairs.

Crucially, Brainard warns that HFT "may amplify market shocks," and the Fed is "studying possible changes in liquidity resilience." As Brainard hints, if liquidity is less resilient, that "could be significant" in times of stress if HFT "acted as an amplification mechanism, impeded price discovery, or interfered with market functioning."

Bloomberg reports,

Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard says central bank is closely watching for changes in the resilience of market liquidity, in prepared remarks Wed. at panel discussion about future of financial market intermediation.

- Brainard speaks in Salzburg, Austria, at global forum on finance

- “An upcoming study of the October 15 event will shine some light on the functioning of the U.S. Treasury market, but there is still much we need to learn,” Brainard says, referring to intraday gyrations in 10-year Treasury yields that day

- “Although anecdotes of diminished liquidity abound, statistical evidence is harder to come by,” Brainard says

- If liquidity is less resilient, that “could be significant” in times of stress if “it acted as an amplification mechanism, impeded price discovery, or interfered with market functioning”

- Regulation may be playing contributing role in reducing broker-dealer bond inventories, but other factors may also be contributing, Brainard says

- High frequency traders’ effect on market liquidity is a topic for further research, and markets increasingly dominated by HFTs “may be less able to absorb large shocks”

So given all that, why is HFT tolerated after all?

Could it indeed be that the only reason why HFT – which has constantly been in the background of broken market structure culprits but never really taken such a prominent role until last night, is because the market is being primed for a crash, and just like with the May 2010 "Flash Crash" it will all be the algos' fault?

This is precisely the angle that Rick Santelli took earlier today, during his earlier monolog asking "Why is HFT tolerated." We show it below, but here is Rick's punchline:

Are regulators stupid when it comes to high frequency trade? Well, i think that there was a time where they were a bit slow to the party. But i don't think it's stupidity or ignorance or not paying attention. So let's wipe that off. So the question i'm asking is, why do they let it continue?

Why is it that anybody would want HFT to be unchallenged or at least not challenge it now? My reason, this is just my reason, when i look at the stock market it's basically at historic highs. When i look at what the federal reserve is doing, it's mostly to put stocks on all-time highs. When i look at all the debt and all the programs that don't seem to be making a difference except for putting stocks on all-time highs, i see that you have this tower of power with regard to the stock market. And nobody wants to challenge or alter hft because it is good to go that many days without having a loss. So my guess is when the stock market eventually deals with reality and pricing, which will come at a time when there's not a zero interest rate policy and we're long past QE, I think they'll address it.

Rick's full clip:

Precisely: when reality reasserts itself – a reality which Rick accurately points out has been suspended due to 5 years and counting of Fed central-planning – HFT will be "addressed." How? As the scapegoat of course. Because since virtually nobody really understands what HFT does, it can just as easily be flipped from innocent market bystander which "provides liquidity" to the root of all evil.

In other words: the high freaks are about to become the most convenient, and "misunderstood" scapegoat, for when the market finally does crash. Which means that those HFT-associated terms which very few recognize now, especially those on either side of the pro/anti-HFT debate who have very strong opinions but zero factual grasp of the matter, such as the following…

- Frontrunning: needs no explanation

- Subpennying: providing a "better" bid or offer in a fraction of penny to force the underlying order to move up or down.

- Quote Stuffing: the HFT trader sends huge numbers of orders and cancels

- Layering: multiple, large orders are placed passively with the goal of “pushing” the book away

- Order Book Fade: lightning-fast reactions to news and order book pressure lead to disappearing liquidity

- Momentum ignition: an HFT trader detects a large order targeting a percentage of volume, and front-runs it.

… will become part of the daily jargon as the anti-HFT wave sweeps through the land.

Why? Well to redirect anger from the real culprit for the manipulated market of course: the Federal Reserve. Because while what HFT does is or should be illegal, in performing its daily duties, it actively facilitates and assists the Fed's underlying purpose: to boost asset prices to ever greater record highs in hopes that some of this paper wealth will eventually trickle down, contrary to five years of evidence that the wealth is merely being concentrated making the wealthiest even richer.

Amusingly some get it, such as the former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, Stephen Roach, who in the clip below laid it out perfectly in an interview with Bloomberg TV earlier today (he begins 1:30 into the linked clip), and explains precisely why HFT will be the next big Lehman-type fall guy, just after the next market crash happens. To wit: "flash traders are bit players compared to the biggest rigger of all which is the Fed." Because after the next crash, which is only a matter of time, everything will be done to deflect attention from the "biggest rigger of all."

* * *

So enjoy the ride for now but Brainard's comments (full speech below) appear to be pre-empting the blame game for when (not if) this bubble blows.

* * *

Recent Changes in the Resilience of Market Liquidity

Recent events and commentary raise concerns about a possible deterioration in liquidity at times of market stress, particularly in fixed income markets. These concerns are highlighted by several episodes of unusually large intraday price movements that are difficult to ascribe to any particular news event, which suggest a deterioration in the resilience of market liquidity. For example, on the morning of October 15, 2014, 10-year U.S. Treasury yields gyrated wildly, and the intraday movement in Treasury prices was 6 standard deviations above the mean. In addition, after 4 p.m. on March 18 EDT of this year, a meeting day for the Federal Open Market Committee, the U.S. dollar depreciated against the euro by 1.75 percent in less than three minutes, an unusually large drop in such a short interval. A few weeks later, markets experienced some very large intraday movements in the price of German bunds during times of little market news.

In contrast, there have been a few notable episodes where market volatility was clearly attributable to significant news but nonetheless appeared to evidence some deterioration in the resilience of liquidity. For example, on January 15 of this year, the announcement by the Swiss National Bank regarding the floor of the exchange rate between the euro and the Swiss franc led to severe disruptions in foreign exchange markets. Separately, the rise in bond yields in May and June 2013, the so-called taper tantrum, also appeared to many observers to have been out of proportion to the news that prompted it.

A reduction in the resilience of liquidity at times of stress could be significant if it acted as an amplification mechanism, impeded price discovery, or interfered with market functioning. For instance, during episodes of financial turmoil, reduced liquidity can lead to outsized liquidity premiums as well as an amplification of adverse shocks on financial markets, leading prices for financial assets to fall more than they otherwise would. The resulting reductions in asset values could then have second-round effects, as highly leveraged holders of financial assets may be forced to liquidate, pushing asset prices down further and threatening the stability of the financial system.

Although anecdotes of diminished liquidity abound, statistical evidence is harder to come by. Indeed, there is relatively little evidence of any deterioration in day-to-day liquidity. Traditional measures of liquidity, such as bid-asked spreads, are generally no higher than they were pre-crisis. Turnover, an alternative measure of day-to-day liquidity, is lower, but it is unclear whether this reflects changes in liquidity or perhaps changes in the composition of investors. The share of bonds owned by entities that tend to hold securities until maturity, such as mutual funds and insurance companies, has increased in recent years, which would lead turnover to decline even with no change in market liquidity. In some markets, the number of large trades has declined in frequency, which could signal reduced market depth and liquidity, but could also reflect a shift in market participants' preferences toward smaller trade sizes.

Finding a high-fidelity gauge of liquidity resilience is difficult, but there are a few measures that could be indicative, such as the frequency of spikes in bid-asked spreads, the one-month relative to the three-month swaption implied volatility, the volatility of volatility, and the size of the tails of price-change distributions for certain assets. We see some increases in the values of these indicators, which provide some evidence that liquidity may be less resilient than it had been previously. But this evidence is not particularly robust, and, given the limitations of the existing data, it is difficult to know the extent to which liquidity resilience may have declined.

As we continue to investigate quantitative evidence of the deterioration in the resilience of liquidity in some of the financial markets, we are also trying to tease out the various drivers of liquidity conditions, such as changes in regulation, trading strategies, and market structure. Regulatory changes are often cited as a contributing factor. Trading financial assets is a balance-sheet-intensive activity, and the Dodd-Frank Act, has created incentives for institutions to carefully assess the risks of such activity through stricter requirements on leverage, liquidity, and proprietary trading, raising the cost of market making and possibly affecting market liquidity. Indeed, there is evidence of reductions in broker-dealer bond inventories in recent years. Nonetheless, since not all broker-dealer inventories are used for market-making activities, the extent to which lower inventories are affecting liquidity is unclear. Moreover, reductions in broker-dealer inventories occurred prior to the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act, suggesting that factors other than regulation may also be contributing. In assessing the role of regulation as a possible contributor to reduced liquidity, it is important to recognize that those regulations were put in place to reduce the concentration of liquidity risk on the balance sheets of the large, highly interconnected institutions that proved to be a major amplifier of financial instability at the height of the crisis.

A second possible contributor may be the growing role of electronic execution of trades across equity, Treasury, and foreign exchange markets and the associated increasing role of high-frequency trading. Competition from high-frequency trading in a particular market may reduce the attractiveness of that market for traditional (manual) traders or slower automated traders, leading to a progressive shift in the composition of market participants toward high-frequency traders (HFTs) over time. This shift could be important to the extent that HFTs may have more limited capacity to support liquidity resilience since, on average, HFTs appear to trade with smaller inventories and lower capital than traditional traders. Although having less inventory and capital reduces the cost of trading, it also means that markets increasingly dominated by HFTs may be less able to absorb large shocks. Thus, liquidity may be sufficient and relatively cheap on normal trading days, but it may not be deep enough to prevent large price swings when demand for liquidity is significantly above the norm. This consideration would be most relevant in the markets that are amenable to high-frequency trading, and automated trading more generally, where assets are fairly standardized, such as equities and U.S. Treasury securities, and less relevant in markets where securities are more idiosyncratic, such as corporate bonds. It is also possible that markets that more readily lend themselves to high-speed trading may be characterized by relatively greater concentration over time. Achieving the speed necessary for high-frequency trading requires large technology investments that necessarily may support a relatively more limited number of market participants. Greater concentration in turn might be associated with lower resilience at times of stress. The possible effect of HFTs on the resilience of market liquidity is an important topic for future research.

Of course, other developments may be affecting liquidity in financial markets. For example, market participants have indicated that changes in participants' risk-management practices may be contributing to reduced market liquidity. In particular, the experience of the financial crisis may have led many participants to reevaluate the risk of their market-making activities and either reduce their exposure to that risk, become more selective, or charge more for it, thereby reducing liquidity.4

It is also worth noting the increased role of asset managers on the buy side of the fixed income markets. During normal market conditions, the demand for liquidity from this group of bond holders is likely relatively small, since asset managers acting on behalf of retail investors generally buy bonds to hold them for some period. Moreover, managers of open-end funds hold liquidity buffers that enable them to respond smoothly to normal redemption demands. However, because the large increase in bond fund holdings is relatively recent, little is known about how these funds will react to periods of market stress or to abrupt changes in financial conditions and the adequacy of their liquidity buffers for such situations. Because funds potentially allow daily redemptions even against illiquid assets, it is possible that redemptions could be magnified in stressed conditions as individuals try to redeem early, which in turn could lead to liquidations of relatively less liquid assets, thereby amplifying price volatility and reducing market liquidity.

If in fact liquidity resilience has declined recently, it may be a transitional development that will be corrected going forward as participants adjust their risk management practices, and the structure of these markets continues to evolve. For example, if traditional providers of liquidity scale back their activity in response to changes in regulation and market structure, over time, this shift may create incentives for other providers, which are not similarly constrained, to step in.

Stress tests, such as those announced by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) offer one way to help ensure that market participants are prepared for sharper spikes in market volatility. For instance, in the Federal Reserve Board's most recent stress test, the severely adverse scenario featured a large decrease in the prices of corporate bonds.

We are in the early stages of data-based analysis of possible recent changes in the resilience of market liquidity. An upcoming study of the October 15 event will shine some light on the functioning of the U.S. Treasury market, but there is still much we need to learn. More broadly, at the Board, we will closely monitor and investigate the extent of changes in the resilience of liquidity in important markets, while deepening our understanding of different contributors and how market participants are adapting.

* * *

Smells like scapegoating to us…

And India has already started:

- INDIA SAID TO CONSIDER ALGO TRADING CURBS TO CHECK MANIPULATION

Would that ever be allowed in America?

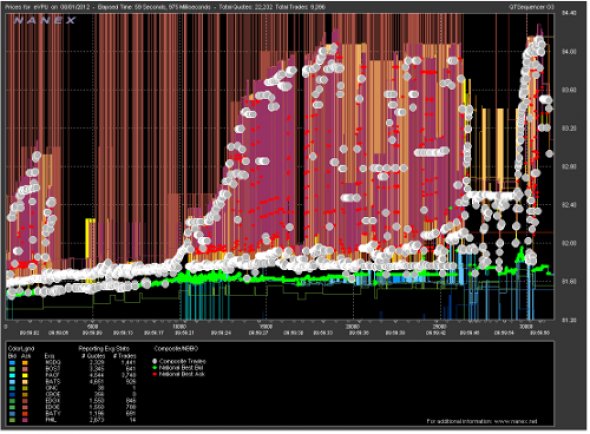

Picture by Nanex via PostMediaLab.org ("A Nanex chart from 08/01/12 showing the bid and the ask in one stock (a utilities ETF), and how at first the bid/ask are tight, but then just before 10:00 AM went totally wild.")