Via Ryan Grim's newsletter (sign up here): "Elizabeth Warren grew up in Oklahoma hearing stories of the dust bowl and the Great Depression, but was married at the age of 19, a mother just a few years later, and did not take a serious turn toward politics until she was well into her 40s. I talked with her about her highly unusual political development. I think that even if you know an awful lot about Warren — a loyal newsletter reader — you’ll find something new in this article. Story is here" [and below]. ~ Ryan Grim

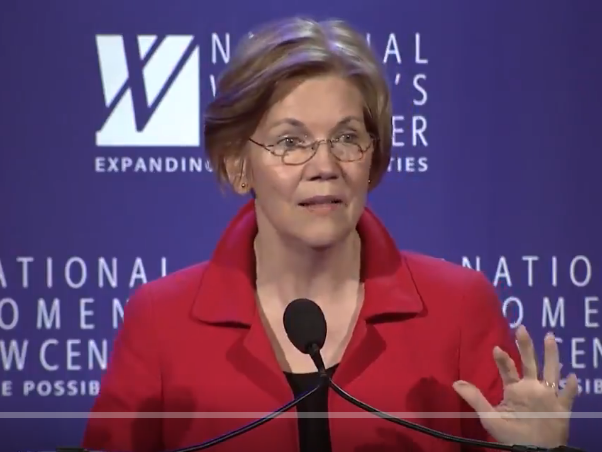

ELIZABETH WARREN ON HER JOURNEY FROM LOW-INFORMATION VOTER

Courtesy of Ryan Grim, The Intercept

ELIZABETH WARREN’S FIRST political memory is from around the time she was six years old, listening to stories about the Great Depression from her grandmother, Hannie Crawford Reed.

ELIZABETH WARREN’S FIRST political memory is from around the time she was six years old, listening to stories about the Great Depression from her grandmother, Hannie Crawford Reed.

“They lost money when those banks closed up,” she said of her grandparents and others in her extended family in Oklahoma. “They watched these little towns shrivel up when the bank was gone. There was no money, there were no jobs. So my grandmother used to say one thing that was political that I can remember. She’d say, ‘Franklin Roosevelt made it safe to put money in banks,’ and she would say, ‘and he did a lot of other things, too.’”

The Depression loomed especially large in her family lore. “I wasn’t born until long after the Depression, until after World War II, but I grew up as a child of the Depression, because my grandmother and grandfather, my aunts, my uncles, my mom and my dad, all my older cousins had lived through the Depression. And it was such a searing experience in Oklahoma, that the Depression hung around our family like a shroud. It was always there,” she said.

As a politician from Massachusetts, Warren has had little incentive to talk about her time growing up in Oklahoma or her early years as a young mom in Texas. But they were formative political experiences, which Warren spoke of at length in a recent interview with The Intercept. Oklahoma, when Warren was a child in the 1950s, was still home to a vibrant movement of populist, prairie Democrats.

“I grew up on the stories [about] my oldest brother,” she said, recalling the family’s harrowing survival of the 1930s, when the dust bowl laid waste to Oklahoma. “Mother used to tell this story about how she’d put Don Reed to sleep and she would wet a sheet — a big regular bed sheet — and she would drape it across his crib so that it went across the top and hung down on the sides to protect him from the dust. And she would come back a few hours later and the sheet would be dry and stiff and covered with caked mud. And that’s how they lived,” she said.

“Out on the farms, the ground was so dry for so long that the ground would crack open enough that a calf could fall in, so farmers took to walking the land to make sure they hadn’t hadn’t lost an animal.”

If she had to guess, she said, she would say that her parents were populist Democrats, fond of FDR, but they never discussed partisan politics. The subject was not a part of her 20s or 30s, either. Warren married young, at the age of 19, and two years later had her first daughter, Amelia, who’d later become her co-author. (The mother-daughter duo co-wrote the 2003 book “The Two-Income Trap” and 2005’s “All Your Worth.”) But at the time the responsibility of caring for her new daughter was an obstacle between Warren and her plans to go to law school. Amelia was two when Warren started at Rutgers and was along for the ride, eventually with younger brother Alexander, as Warren would grow to become a professor, author, researcher — and now senator and potential White House contender.

In early polling on the 2020 Democratic Party presidential primary, Warren and Bernie Sanders, representing the Democrats’ progressive flank, consistently garner at least 40 percent of the vote between them. The rest are scattered among other hopefuls, ranging all the way from Kirsten Gillibrand to Oprah Winfrey and The Rock.

But while Sanders and Warren may have wound up in similar spots on the ideological spectrum, at least in the public eye, they took very different routes to get there. Sanders took a traditional path, reading Marx and throwing himself into the civil rights, antiwar and environmental movements, followed by support of indigenous movements in Central America in the 1980s. He kept an arms-length relationship with the Democratic Party, willing to engage in electoral politics, but not on the party’s terms — caucusing with it while in the House and Senate but never formally joining.

Warren, by contrast, was for decades what a political consultant might refer to as an infrequent voter, often missing midterms and primaries. And, despite her formidable education and intellect, she was a low-information one at that.

Her first presidential vote, in 1972, was cast against a man she said she disliked passionately, Richard Nixon. But reflecting how little she was paying attention to day-to-day politics at the time, she couldn’t immediately recall who had been running against him. When told it was Democrat George McGovern, she said that yes, she would have voted for him, but didn’t have any specific memory of having done so. (She was living in New Jersey at the time.)

Going to the polls, she said, was nothing new for her. Warren’s mother had been a poll worker, and brought her young daughter to the polls each Election Day.

Nixon was re-elected that year, of course, but resigned, and was replaced by Gerald Ford. Warren said she voted for him in 1976, believing that “Ford was a decent man.”

But she was happy with Jimmy Carter, who beat him. “I thought he [also] was a decent man,” she said, transferring her then-standard for what she wanted in a politician from Ford to Carter. “He was a really good man.”

As the ‘80s wore on and her research on bankruptcy progressed, she started waking up politically. At the time, though, the two parties had yet to separate entirely along ideological lines, as some deeply conservative and racist Democrats still held office, as did some genuinely liberal Republicans.

In 1988, Warren voted for Michael Dukakis but in 1992, split her ticket, voting for Republican Arlen Specter for Senate and Democrat Bill Clinton for president. Specter is a good example of the one-time flexibility of the party system and the politicians within it: He began and ended his career as a Democrat, but was a Republican for much of the middle of it.

By the fall of 1987, she had moved to Pennsylvania and registered there as a Republican. Warren said she couldn’t quite remember why she did it but that she was a fan of Specter. “Again, I thought he was a decent man,” she said. She couldn’t recall whom he ran against. (His Democratic opponent was Lynn Yeakel.)

That GOP registration, though, has set off speculation over the years that one of the Senate’s most progressive champions may have at one time been a Ronald Reagan backer.

So we asked her: Is it true? Is it possible the champion of the regulatory cops on Wall Street voted for the man who made deregulation a hallmark of his presidency?

No.

In 1980, she said, she was a registered independent living in Missouri City, Texas, and cast her vote to reelect President Carter.

When Reagan won, she wasn’t happy, but not crushed the way she was on election night in 2016. “I was disappointed and didn’t like him, but I wasn’t deeply worried for the country, not anything like when Trump was elected,” she explained. If she could go back in time, she said, she would tell herself “this was a far more pivotal historical moment than you understand.”

Indeed, her most recent book divides the 20th century into two pivotals epochs, 1935 to 1980 and then 1980 to 2016.

As that history was unfolding before her, she was becoming increasingly aware of what was going wrong with the country. In 1978, Warren divorced, remarrying within two years. In 1981, she began working with Jay Westbrook and Terry Sullivan on what would become a lifelong project investigating the causes of bankruptcy, a study that continues up through today.

Warren said that when she went into her bankruptcy work, she was to the right of her collaborators. Westbrook confirmed that recollection. “I would have said when I first met her that that she was closer to being a moderate Republican. She never said that to me in so many words that I remember, but if somebody had said, hey, Jay, what are Liz’s politics, I’d have said, well, I don’t know, but I’d guess that she’s a moderate Republican,” Westbrook said.

“When we went into the whole consumer bankruptcy thing, I think her attitude was very much balanced between, on the one hand, no doubt there are people who have difficulties and they’re struggling and so forth, and on the other hand, by golly, you ought to pay your debts, and probably some of these people are not being very committed to doing what they ought to do.”

Warren said that doing the work changed her politics.

“Terry [Sullivan] and Jay went into that with a pretty sympathetic lens, that, these are people, let’s take a look, give them the benefit of the doubt that they had fallen on hard times,” she said. “I was the skeptic on the team.”

Her own experience shaped how she saw the families she was studying. Raised on what she has called “the ragged edge of the middle class,” she was the youngest of four, with three significantly older brothers. When she was 12, her father had a heart attack and lost his job, throwing the family into financial turmoil. The car was lost and the family house was on the line when her mother was able to get a minimum wage job at Sears, which paid enough at the time to keep the family afloat until her father could recover. She talks often about the experience today to make a variety of points — both to demonstrate that she knows what it means to struggle, but also to talk about how a fairer economy and a more robust minimum wage made it possible for her family to survive.

In the early 1980s, it shaped her worldview differently. “I had grown up in a family that had been turned upside down economically, a family that had run out of money more than once when there were still bills to pay and kids to feed — but my family had never filed for bankruptcy,” she said. “So I approached it from the angle that these are people who may just be taking advantage of the system. These are people who aren’t like my family. We pulled our belts tighter, why didn’t they pull their belts tighter?”

But then she dug into the stories of those who had. “Then we start digging into the data and reading the files and recording the numbers and analyzing what’s going on, and the world slowly starts to shift for me, and I start to see these families as like mine — hard working people who have built something, people who have done everything they were supposed to do the way they were supposed to do it,” she said. Now they “had been hit by a job loss, a serious medical problem, a divorce or death in the family and had hurtled over a financial cliff. And when I looked at the numbers, I began to understand the alternative for people in bankruptcy was not to work a little harder and pay off your debt. The alternative was to stay in debt and live with collection calls and repossessions until the day you die. And that’s when it began to change for me.”

Westbrook, who has spent years in bankruptcy courtrooms, said that the same phenomenon routinely happens with judges. Even a lawyer who spends his or her career before the bench as a lawyer for creditors gradually shifts, he said, under the weight of seeing, day after day, good families destroyed by bad luck.

From there, said Warren, she zoomed out from the particular stories of hardship she was encountering and began asking why she was seeing so much more of it in the 1980s than she had before.

“This happens over the space of a decade, I began to open up the questions I asked. I started with the question of the families who use bankruptcy. But over time it becomes, so why are bankruptcies going up in America?” she said. “The numbers just keep climbing every year to where we’re getting well over a million families each year filing for bankruptcy. Because people — this is the other half of it — people have lost jobs and gotten sick and been divorced for decades, but bankruptcy filings had stayed far lower. What was changing in the 1980s and 1990s? What difference was there in America?”

The answer to that question, she said, led her to become a Democrat. “I start to do the work on how incomes stay flat and core expenses go up, and families do everything they can to cope with the squeeze. They quit saving. They go deeper and deeper into debt, but the credit card companies and payday lenders and subprime mortgage outfits figure out there’s money to be made here and they come after these families and pick their bones clean. And that’s who ends up in bankruptcy. So that’s how it expands out. And by then I’m a Democrat,” she said.

By the mid-’90s, she had accepted a job at Harvard and by then was a full-fledged, registered Democrat, she said, a claim backed up by voter registration records.

Westbrook pinpointed her turn toward becoming a partisan Democrat to her appointment to the National Bankruptcy Review Commission. Being a part of that panel, he said, put her into contact with high-level politics in a way she’d never been before. Her work on that commission led to her subsequent lobbying around bankruptcy reform.

Becoming a partisan is difficult for a scholar, Westbrook said. Academic researchers start with a question, collect data, analyze it, and form a conclusion. Partisans start with a conclusion — say, taxes are too high or spending on infrastructure is too — and find data to back it up.

That could partially explain why Warren has not in fact proven to be a reliable partisan, willing to criticize President Obama for being too soft on Wall Street, or then-Sen. Hillary Clinton for voting the wrong way on bankruptcy reform.

After the financial crash, as she stepped her lobbying on behalf of her brainchild, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, she thought back to those moments at the knee of Grandma Hannie. Barney Frank, then the House Financial Services Committee chairman, told Warren he wanted to regulate the banks before turning to the consumer bureau.

“One of the earliest conversations we had about how to think about financial reform in the wake of the 2008 crash was, what goes first? What’s the first thing we need to think about? And Barney wanted to start with the nonbank financial institutions,” she said, “and stronger regulations over the largest too big to fail banks.”

Warren agreed that the argument made sense on a policy level, but politically, it was important to win people’s trust. “I argued back to Barney that we needed to start where the crash had started, and where families understood it and felt it and that was, family by family, mortgage by mortgage, how those giant banks had taken down the economy. He and I were kind of going back and forth and then I said, ‘Barney, let me tell you about my grandmother,’ and I told him that story,” she said. “Once he made it safe to put money in banks, my grandmother trusted Franklin Roosevelt. And so my argument to Barney was, start where people will understand what we’re trying to do. And that’s with the consumer agency. And Barney sat there for maybe — you know Barney, he has the quickest mind on earth — he cocked his head, it took about three seconds and he said, ‘You’re right. We’ll start with the consumer agency.'”

It was uncanny insight for a politician, and it was made possible, perhaps, by the decades she spent before becoming one. If Warren’s launch into politics is accurately pinpointed to 1995 with her commission appointment, that would mean that well into her 40s she was still living, voting and thinking, politically speaking, at least, like a regular person. That’s an unusual path for a politician.

****

I'm the Washington bureau chief at The Intercept, and I send this several times a week. If you want to contribute directly to help keep the thing running, you can do so here, though be warned a donation comes with no tote bags or extra premium content or anything. Or you can support it by buying a copy of Out of the Ooze: The Story of Dr. Tom Price or Wall Street's White House, the first two books put out by Strong Arm Press, a small progressive publishing house I cofounded.