A Touch Better

Courtesy of Scott Galloway, No Mercy/No Malice, @profgalloway

Of all media channels, I find writing books the most difficult — and rewarding. (A decent metaphor for anything.) I believe each of us has a camera in our brain that observes everything we do and registers if we’re adding value. Sweating, caring, concentrating all report to a central authority that secretes the right chemicals to extend, or end, our time on Earth based on how much/little value we’re adding. I work out a lot to fool my brain into believing I’m hunting or building housing and write to stay in mental shape. So I’ve committed to writing a book every 18 months until … I start the march to the next thing. The last sentence is disingenuous: I don’t believe there is a “next thing.”

Anyway, my next book, Adrift: America in 100 Charts, comes out September 20. It’s a narrative told through (wait for it) charts. The data presented in the charts isn’t neutral or infallible, but it can be clarifying and might even create common ground.

Between now and the release, I’ll share a few excerpts from Adrift, because they’re good, and I hope they’ll encourage you to buy a copy. Which you can do here. The first excerpt is from Chapter 2, “The World We Made.” In this section, I step back and recognize the extraordinary virtues of our age. I was on Michael Smerconish last week, following Steven Pinker. Professor Pinker believes, despite all the negative news, the trend line is upward. It’s unlikely we’ll ever see the headline: “Things a Touch Better Today, Globally.” This chapter takes an optimistic stance (not easy for me), as Steven does, and acknowledges that despite our myriad challenges, the world is becoming a better place.

The World We Made

The ascent of the American economy after World War II, coupled with the advances of technology, brought unprecedented prosperity not just to the U.S., but to the human race. It’s tempting to let the costs of that prosperity obscure it, but a sober accounting of America and the world today would be incomplete without recognizing our enormous gains.

The world is significantly wealthier, freer, healthier, and better educated than it was forty years ago. In 1980, over 40% of humanity lived in extreme poverty. Today, less than 10% does. In 1980, 44% of humanity had no democratic rights. Today, it is less than 25%. A child born in 1980 had a life expectancy of 63 years. A child born today should live a decade longer. In 1980, 30% of people fifteen years and older had no formal education. By 2015, that share had been cut in half.

These were global gains, but America lay at the heart of them. U.S. innovation in everything from transport to advertising supercharged the consumer culture of the postwar era into an upward dance between demand and manufacturing agility.

The billions lifted from poverty since 1980 were largely in Asia, and their means of ascent was making consumer goods for U.S. and European markets. Those same economies are today converting to knowledge work and middle-class lifestyles, in substantial part on the foundation of digital technologies developed in the former orange groves of the Bay Area.

We tend to focus on things that did occur, but we shouldn’t overlook crises that were averted. The demise of the Soviet Union posed an apocalyptic risk. By 1989, the Soviets commanded 39,000 nuclear warheads and the world’s largest standing army. Managing the sudden collapse of one of history’s largest empires could have gone very, very badly. At one point, the Soviet government sold twenty naval combat ships for cases of Pepsi. But postwar institutions crafted and nurtured by the Western nations held firm.

For better or worse (it’s both), the headline change is increased global connectivity. The term “globalization” has been loaded up with the anxieties of our era, but it represents a profound change in the human condition beyond the concerns of the moment. Never before has human knowledge been so widespread, nor have creators, from artists to manufacturers, had access to such a breadth of markets—and competitors.

Productivity Revolution

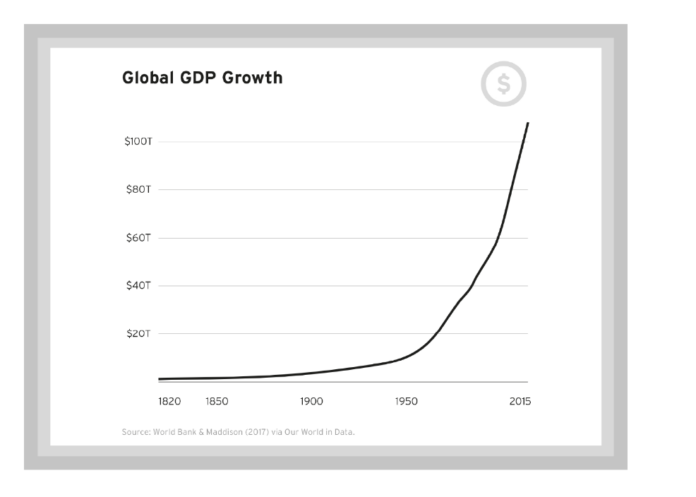

Modern civilization rests on a foundation of unprecedented, once even unimaginable productivity. The rebuilding of Western Europe and the conversion of the U.S. wartime economy after World War II doubled the globe’s annual economic output in less than a decade. By 1960, the world was producing twenty times as much as it had in the early nineteenth century.

Then, as the relatively easy gains from the postwar boom wound down, the real miracle happened. From 1980 to 2004, the world’s economic output doubled again, from $35 trillion to $70 trillion. In just twenty-four years, a single generation, as much economic potency had come online as had taken the human species its entire history to accumulate. Today, the world generates roughly as much output in a month as it did in the year 1950.

Billions of People Work Their Way Out of Poverty

In less than forty years, billions of people have improved their lot and escaped extreme poverty. That’s a low bar—$1.90 per day, which is subsistence living even in low-cost economies—but it’s still a change for the better unlike anything in history.

The rolling back of poverty has been particularly remarkable in China. In 1990, 750 million Chinese lived below the international poverty line. Today, it’s less than 10 million. Most of these people still have low incomes, but the economic engine they’re a part of continues to churn. In 2019, there were 100 million households in China with wealth of more than $110,000.

The modern world order has ample flaws, but sometimes the scale of our achievement is so vast, it becomes a static backdrop we lose sight of.

Health Is Wealth

Thanks to substantial improvements in health care, sanitation, education, and economic opportunity, people all over the world are living longer. Infant mortality has been cut by two-thirds since 1990; disease and war claim fewer lives. This is the ultimate measure of prosperity and human accomplishment: more life.

More life, I like that. Next week I’ll return to everything that’s wrong.

Half-full/empty is a matter of perspective. My night was ruined by my boys, who don’t listen and only speak to me when they need something. However, that also suggests we’ve raised confident boys who no longer need us, and indicates their parents are able to give them things our parents couldn’t for us. My evening’s ruin is a function of how wonderful the base line has become. People who need and love me, and let me need and love them back.

Life is so rich,

![]()

P.S. Sign up for a free Section4 account, and you can watch the first lesson of every single sprint we offer (including both of mine). You can end your day at least 2% smarter — sign up now.