Courtesy of Gonzalo Lira

So today, two bits of news came out: Unemployment declined to 8.9% last February, as the U.S. economy added 192,000 jobs; and the Federal Reserve signalled that it is definitely-definitely-definitely ending Quantitative Easing 2 (QE-2) in June, as originally scheduled, on the assumption that the economy is improving, and therefore no further extension of QE-2 will be necessary.

|

| Portrait of the author, chewing over what it all means. |

On its face, this would seem to be . . . not good news, but at the leastencouraging news: The economy seems to be improving, albeit anæmically.

But is it?

Stepping on the heels of the Bureau of Labor Statistics release of the employment figures, Tyler Durden at Zero Hedge pointed out that, based on the 25 year average of employment participation of 66.1%, U-3 unemployment ought to be at 11.6%—quite a bit higher than the current 8.9% headline number.

This points to something that a lot of commentators of the BLS’s numbers have been saying for a while: The number of individuals in the labor market as defined by the BLS has been steadily dropping. But it hasn’t been because of some sudden demographic shock—it’s been because more people have been unemployed for more than two years.

So-called “Ninety-Niners”—people who have been unemployed for more than 99 weeks, and have therefore run out of unemployment insurance—are dropping out of the BLS accounting for unemployment.

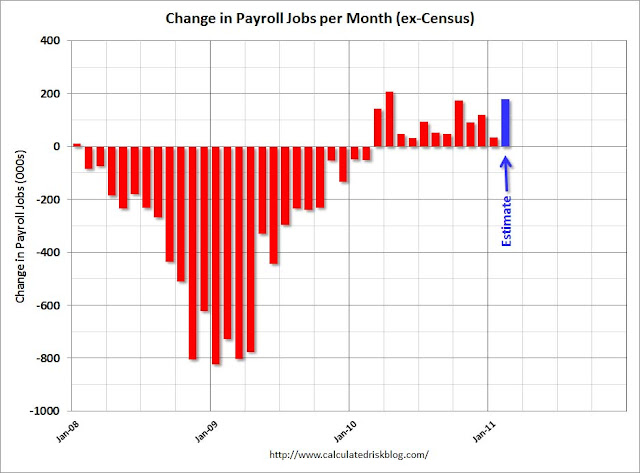

Calculated Risk pointed to the peak of job losses—the first quarter of 2009—and how those individuals would be running out of unemployment benefits right about, well, now. The money-quote from CR:

This graph shows the change in payroll jobs each month. The peak job losses were in early 2009—and 99 weeks is just under two years—so many of those people will be exhausting their benefits over the next few months.

Continue here >