Courtesy of Yves Smith of Naked Capitalism

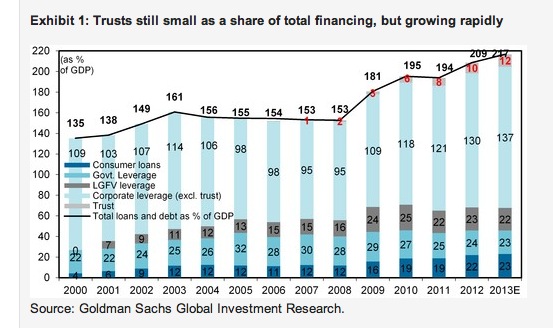

The government does have the luxury of a known drop-dead date to decide what to do about an imminent large default in its shadow banking system. We’ve written off and on about how important it has become to providing new loans in the last year, rising from 20% to 30% of the total (and experts think it’s really more like 50%), and lending has in recent years been the driver of growth, but each yuan of new borrowing now produces 1/4 the amount of GDP increase that it did five years ago.

One bit of good fortune for the officialdom is that its first major test of the shadow banking system is known in advance, giving them time to decide what to do and take any needed precautionary measures. China Credit Trust Co. has told investors it may not make a January 31 principal repayment on a 3 billion remnimbi trust product. Various financial sites, including this blog, have taken note of the concerns about default in China’s so-called wealth management products, an important source of funding for provincial real estate projects. WMP are somewhat cleaned-up cousins of structured investment vehicles. Both funded short and lent long in supposed off balance sheet vehicles. But the maturity mismatch is less with wealth management products, and the authorities apparently believe that investors will not be able to pressure banks into supporting these investments.

The China Credit Trust product isn’t considered to be a WMP; it’s a different structure, a trust, which is sold to particularly well-heeled investors. And the maturity mismatch is even lower than for a WMP, in theory reducing the market risk even further. A Goldman report, excerpted at MacroBusiness, explains:

A trust is essentially a private placement of debt. Investors in the trust must meet certain wealth requirements (several million RMB in assets would not be unusual, so the investors are either high net worth individuals or corporates) and investments have a minimum size (e.g. RMB 1mn)…Trusts invest in a variety of sectors, including various industrial and commercial enterprises, local government infrastructure projects (via LGFVs), and real estate…

A trust is not to be confused with a “wealth management product” (WMP). WMPs are available to a broader group of individuals, with much smaller minimum investments…Funds from WMPs may be invested in a range of products including corporate bonds, trust loans, interbank assets, securitized loans, and discounted bills—so WMPs are best thought of as a “money market fund” or pool for other financial products.

The real problem is that trusts aren’t that large in terms of total outstandings but they’ve become important sources of new lending in recent years:

With a large volume of trust products scheduled to mature this year, who bears the losses in the event of a default could set an important precedent. In our detailed research on the China credit outlook last year (see “The China credit conundrum: risks, paths, and implications”, July 26, 2013), we explicitly identified “removal of implicit guarantees” as one of four potential ‘risk triggers’ for a broader credit crisis. If the realization of significant losses by investors causes others to pull back from funding various forms of “shadow banking” credit, overall credit conditions could theoretically tighten sharply, with consequent damage to growth.

From the perspective of policymakers, the default of a trust under the current circumstances might be seen as having less risk of contagion than some other “shadow banking” products. First, the trust is explicitly not guaranteed by either the trust company or the distributor. Second, the investor base of a trust is typically a relatively small group of wealthy/sophisticated investors (the minimum investment in the CCT trust mentioned above was RMB 3mn). This contrasts with broadly offered wealth management products, which have many more individual investors with less investment experience and more modest personal finances. Third, the particular circumstances of this trust (lending to an overcapacity sector, failure to obtain key business licenses, arrest of the borrowing company’s owner) might make it easier for authorities to portray as a special case. Put another way, if the authorities felt obliged to provide official support to this product, it is not clear under what circumstances they would be comfortable letting any trust or wealth management product default.

So as much as the amounts involved are large, there’s good reason to think this default might be, to use that famous Bernanke expression, contained. But this likely default comes against a backdrop of increasingly difficult conditions. China’s manufacturing index registered contraction, putting more pressure on government officials to keep a credit contraction at bay. From Bloomberg:

The preliminary reading of 49.6 for January in a Purchasing Managers’ Index (SHCOMP) released today was below a final figure of 50.5 in December and all 19 estimates of analysts in a Bloomberg News survey. A number above 50 indicates expansion….

The PMI reading is “really dramatic,” Hu Yifan, chief economist at Haitong International Securities Co. in Hong Kong, said in a Bloomberg Television interview. Rising funding costs are adding difficulties and the official PMI will also show a “continued declining trend,” she said.

And for some time, Chinese officials have been gingerly trying to slow growth in order to tamp down inflation (rising inflation was starting to become divisive). Now, as Ambrose Evans-Pritchard writes, the Middle Kingdom is additionally trying to deleverage. But that’s contractionary. Will it stick with its own medicine? From his account:

China is walking a tightrope without a net. There is an acute cash crunch. Credit at a viable cost is being fiercely rationed. Foreign buyers with money in hand can – and are – buying up nearly completed buildings from distressed developers for a song…

“They are trying to deleverage without blowing the whole thing up,” said CITIC’s Zhang Yichen.

“The M2 money supply is 120 trillion RMB but that is still not enough cash because velocity of money is very slow, and interest rates are going up.”

“My guess is that they will manage it. The US couldn’t contain Lehman contagion but in China all contracts can be renegotiated, so it is very hard to have a domino effect. We’ll see a slow deflating of the bubble,” he said…

There was general agreement that there will be “no more stimulus” for now. President Xi Jinping is determined to tough it out…

Nothing said changes my mind that China is riding a $24 trillion credit tiger that it cannot really control. Loans have jumped from 120pc of GDP to around 220pc since the post-Lehman blitz (George Magnus from UBS says it may be 250pc by now).

As Fitch says, this is an unprecedented rise in the credit-GDP matrix in any large state in modern times. It will not end with a Western style banking crash because the financial system is an arm of the state. It will end in an entirely different way.

Japan had a grinding-down of market prices over a period of years, even as the government tried restoking the economy. And when it thought it had gotten a real recovery and withdrew support, it did get a series of financial collapses. Now the credit overhang in China isn’t believed to be as bad as Japan’s, so it has more room to navigate an exit. But the flip side is that Japan’s credit hangover took place when global growth was strong and the West tolerated Japan continuing to run large trade deficits.

To put this more simply, everyone, even the Chinese officials, seem to recognize that the old Herbert Stein saying, ‘If something cannot go on forever, it will stop,” is close to becoming operative for them, and they are trying to be pro-active. But no country has ever navigated from being export and investment dependent to being consumption-driven without undergoing significant upheaval. Given the lack of models for what the Chinese are trying to accomplish, I’m not sure that optimism, even of the muted sort, is well placed.

Picture credit: Tom Patterson, Cycle Editing