Courtesy of The Automatic Earth.

Detroit Publishing Co. Japanese Rolling Balls, Coney Island, Cincinnati 1910

We’ve carried a lot of news on Japan’s deteriorating economic and financial situation so far this year (and before), but perhaps it’s now time to wonder how much longer until the rising sun comes apart at the seams. To date, the worst fears over a trend of deflationary pressures, diminishing wages and enormously bloated government debt were somewhat cooled by the assumption that the Japanese people were still avid savers, and so they would be able to withstand quite a bit of turmoil. But that may now have come to an end. And what happens after is very hard to tell, David Stockman calls it a financial no man’s land. What seems certain is that yields on government bonds will soar. Putting pressure on both government and households that will feel like suffocation. Japan has printed its way into survival for decades, and that escape route, the only one they had, looks to be blocked soon. Stockman:

How Japan Blew Its Savings Surplus: What A Keynesian Dystopia Looks Like

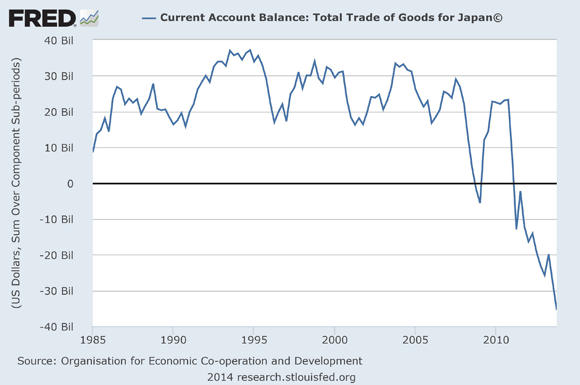

Financially speaking, Japan is fast becoming a Keynesian dystopia. Its entire economy is now hostage to a fiscal time bomb. Namely, government debt which already exceeds 240% of GDP and which is growing rapidly because even the recent traumatic increase in the sales tax from 5% to 8% does not come close to filling the fiscal gap. Moreover, even at today’s absurdly low and BOJ rigged bond rate of 0.6% nearly 25% of government revenue is absorbed by interest payments. Now comes the coup de grace. Japan’s savings rate has collapsed (see below) and its vaunted current account surplus is about ready to disappear.

This means Japan’s accounts with the rest of the world will cross-over into a “financial no man’s land”; it will be forced to steadily liquidate its overseas investments to pay its current bills—an investment surplus built up over the course of 50 years. But this will also reduce foreign earnings and thereby expand Japan’s growing deficit on current account. Accordingly, to finance its “twin deficits” it will have to attract massive amounts of foreign capital for decades to come—an imperative which will require a devastating rise in interest rates, perhaps as high as 4% according to one expert :

The yield on Japan’s benchmark 10-year government bond, now around 0.6%, could rise to 4% – a level unseen since March 1995 — should the current-account balance drop into deficit as public debt eclipses the nation’s savings, said Toshihiro Nagahama, chief economist at Dai-ichi Life Research Institute.

Needless to say, were the carry-cost of Japan’s towering fiscal debts to rise by even half that much it would be game over. Interest expense would absorb virtually 100% of current policy revenue, forcing the government to raise taxes over and over. One expert quoted in the Bloomberg article below says that a sales tax of 20% – nearly triple the recently enacted level – would be required to wrestle down the fiscal monster that would result from interest rate normalization.

Unless the government raises the sales tax to 20% or makes drastic reform on social welfare spending, this scenario is highly likely,” said Ogawa. “Higher interest rates will discourage domestic capital investment and spur the shift of production abroad, increasing the number of people unemployed.”

The above quote strongly hints why Keynesian dystopia is an apt description of what is emerging in Japan; and why that descriptor is also reflective of the financial horror show that is coming to our own financial neighborhood a decade or two down the road. As indicated above, the alternative to an economy killing 20% sales tax is “drastic reform of social welfare spending”. But the latter is not even a remote possibility. Japan’s population is both shrinking and also aging so rapidly that it’s fast on its way to become an archipelago of old age homes.

Here is what happened to the Japanese rate:

Japan savings rate as shown below has dropped from in excess of 20% during its 1970s and 1980s heyday as a mercantilist export power to only 3% today. When Japan’s retired population reaches nearly 40% of the total in the years ahead, this rate will obviously go negative as households liquidate savings in order to survive.

On May 14, the Wall Street Journal ran a piece by Eleanor Warnock that had an updated and slightly different chart, and that suggested savings in the fiscal year through March may have already been below zero:

Are Japanese Eating into Their Savings?

Once some of the world’s biggest savers, Japanese likely dipped into their savings and spent more than they made in the fiscal year through March, the first time Japan’s households have been in the red on an annual basis since World War II. Economists say that gross domestic product data due Thursday will suggest Japan’s household savings rate – the ratio of savings to disposable income – turned negative in the last fiscal year.

That’s because household spending likely jumped 2.4% on year in the period, according to forecasters, largely due to rush demand ahead of a sales-tax increase that took effect April 1. That would be the biggest rise in household spending in a fiscal year since 1996. Since disposable income remained flat, economists say, it was likely enough to help push the household saving rate into the red.

Teizo Taya, an economist and former member of the Bank of Japan policy board who estimates a negative savings rate of between 0.2 and 0.4% in the last fiscal year, says consumer spending might be strong enough to withstand the sales-tax hike. “If the decline continues, the current recovery may be able to continue even in the face of the tax hike,” Mr. Taya said. But there are sizeable risks as consumers become more spendthrift. One is that wages don’t rise concomitantly. That could leave Japanese saddled with debt and crush the newfound optimism.

“It’s not a very good thing for the household savings rate to fall in the red, as it’s a sign that consumers aren’t making enough,” said NLI Research Institute economist Taro Saito, who expects a negative savings rate of 0.4% in the just-ended fiscal year. Another risk for Japan, where public debt is more than three times annual national output, is that a negative savings rate leaves the economy more dependent on foreign financing. Japan boosters have long argued the country can sustain its large debt, the biggest among industrialized nations, because it can borrow from a large pool of domestic savings. Any change in that is a risk.

That last point there is the money quote: the government had been able to continue borrowing because Japanese savers bought its bonds. with a negative savings rate, it no longer can. And foreign investors won’t pick up the slack at an 0.6% rate. I’d also like to note that suggestions that an economy can recover because its people get poorer, don’t fly with me. That’s just economics mumbo jumbo. And we’re not done yet. Stockman continues:

What happened to Japan’s huge savings surplus? The government borrowed it! And wasted it on massive Keynesian stimulus projects that kept the LDP in power for decades but produced bridges and highways to nowhere that will be of no use to Japan’s retirement colony as it ages. And the adverse demographic tide is indeed powerful as shown by the curve below on Japan’s working age population. In a few short years what was a working age population that peaked at 88 million has dropped to 79 million; and it will plunge to below 50 million persons in the next two decades.

What the Keynesian witch-doctors who advised Japan to bury itself in fiscal stimulation after its financial crisis of 1989-1990 did not explain was how this inexorably shrinking working population could possibly shoulder the tax burden needed to carry Japan’s massive public debt. Yet there is no other way out of the Keynesian debt trap in which Japan is now impaled. As the current account, also shown below, continues to worsen, the need to import capital to fund the gap will drive interest rates sharply higher. The burden on Japan’s remaining taxpayers will become crushing.

I don’t find that Stockman’s arguments become stronger when his every second word is Keynesian, quite the contrary, but that’s his hobby horse right now. Not that he’s wrong, but we already got it, and this is not a game of pick your ideology; it’s much more. Stockman then has a pair of devastating and illuminating graphs:

… the graph below should be pasted on every US Congressman’s forehead. When the debt spiral goes too far – it becomes a devastating financial trap. And it cannot ultimately be solved with money printing because if carried to an extreme – even for the so-called reserve currency – it will destroy the monetary system entirely.

It should also never be forgotten that the drastic degeneration of Japan’s public finances happened in real time – within less than two decades after its leadership was bludgeoned into one fiscal spasm after the next by Keynesian officialdom in the US Treasury, the IMF, the OECD and elsewhere. And this is clearly a case of bad ideas imported from abroad. The generation of officials who lead Japan’s post-war miracle may have been hopelessly addicted to unsustainable models of mercantilist export promotion and currency pegging, but they were not believers in Keynesian borrow and spend.

It’s not just US Congressman who should look at the graphs above and below, it’s European leaders and Chinese party members too, and everyone else. You cannot fight too much debt with more debt. You can perhaps fight some that way, but not too much of it. And while nobody has the government debt that Japan has – as of yet -, how is any major country going to keep itself from going the exact same way if current trends hold?

And we’re still not done. Because Shinzo Abe’s hand is diving and delving deeper into the pockets of the world’s largest pension fund, and ordering it to sell off Japanese bonds into a market that really has just one buyer, the Bank of Japan. As if Abenomics wasn’t scary enough yet, or enough of a failure. This is the Wall Street Journal’s same Eleanor Warnock’s take:

Giant Japanese Fund Set to Invest More in Stocks, Foreign Bonds

Japan’s $1.26 trillion public pension fund will likely announce a boost to stock and foreign-bond investments in early autumn, the head of its investment committee said Tuesday, potentially sending tens of billions of dollars into new markets. A shuffle at the world’s largest pension fund would achieve one of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s objectives and could help invigorate Japan’s economy, which is beginning to emerge from a decadeslong era in which investors mostly avoided risk. [..]

She tries the positive spin approach, but does include a warning too:

The changes could raise uncertainty for tens of millions of Japanese who count on steady pension payouts in retirement. With its traditional focus on Japanese sovereign debt, the fund has performed relatively well in recent years despite extremely low debt yields, in part because the country’s deflationary environment was good for bonds. “The [Government Pension Investment Fund] shouldn’t be used as a tool for short-term-oriented intervention in asset markets. It’s not a piggy bank for short-term policy purposes. Each penny of the GPIF is pension money,” said Nobusuke Tamaki, a former fund official who now teaches at Otsuma Women’s University.

While David Stockman has no intention of taking any prisoners:

• Japan Pension Fund Plans Masssive Bond Dump Into Dead Market (Stockman)

So this is how it works. Japan has the most massive public debt in the world relative to national income, but the implicit aim of Abenomics is to destroy the government bond market. After all, if inflation goes to 2% or higher, government bonds yielding 0.6% will experience thumbing losses. Even the robotic Japanese fund managers no longer want to hold the JGB—- as evidenced by another session when no future contracts on either the 10-year or 20-year bond changed hands. As Zero Hedge noted,

You know things have got a little too strange when the largest government bond market in the world saw no futures trades in the morning session last night.We may complain in the US of falling volumes but none, zero, zip, nada is about as low as it gets; and that is how many trades occurred in the 20Y futures contract in Japan (and 10Y cash bond market). This is not the first time as Mizuho warned in Nov 2013 that “to all intents and purposes, there is no JGB market.” And this lack of trading on a day when major macro data printed far worse than expected … well played Abe … you entirely broke your bond market.

In effect, the BOJ is the bond market—that is, the buyer of first, last and only resort. Yes, there are upwards of $12 trillion of Japanese government debt and other obligations outstanding. In normal times, a bond market that didn’t trade in the context of such a massive overhang would have produced sheer panic and bedlam among officialdom. But not in this Keynesian day and age. The implicit assumption is that the BOJ can ultimately buy all the bonds ever issued and the massive outpouring of new bonds yet to come.

After endless prodding by the Abe government, Japan’s pension system (GPIF) will now begin to massively dump hundreds of billion of JGBs. This is being done, of course, to stimulate the Japanese economy by putting pensioners in harm’s way. The cash to be derived from this program of bond dumping will used to purchase Japanese and international equities, along with real estate, private equity, hedge funds and other “alternative asset” classes. And who will buy negative return bonds to be dumped by the GPIF? Why, the BOJ. In Japan, all financial roads lead to the printing press.

Both Japan’s government and its central bank demonstrate in living color what the limits are for governments and central banks when it comes to manipulating economies and markets. And it would be a very good idea for all their peers worldwide to take note. And all of their underlings too. But I have a hunch we will need to see this through to its bitter end before that happens. When its economy crashed early 1990s Japan made one fatefully horrible decision: to not cleanse its banks of their debts, to do basically no defaults or restructuring. And this is the price they’re going to be paying for that decision: once there are no buyers for their cheap debt anymore, the fall will be deep, steep and fast. The rapidly ageing population will see their pension provisions plummet in value, and everyone will see taxes rise more than they can presently imagine just to keep a semblance of a government in place. If we keep up the same approach, in Europe and the US, our foreland too will be no man’s land and nowhere.