Can mirrors boost solar panel output – and help overcome Trump's tariffs?

Now that panel costs in U.S. will go up, will reflectors make a comeback? Joshua M. Pearce, CC BY-SA

By Joshua M. Pearce, Michigan Technological University

Falling costs for solar power have led to an explosive growth in residential, commercial and utility-scale solar use over the past decade. The levelized cost of solar electricity using imported solar panels – that is, the solar electricity cost measured over the life of the panels – has dropped in cost so much that it is lower than electricity from competing sources like coal in most of America.

However, the Trump administration on Jan. 22 announced a 30 percent tariff on solar panel imports into the U.S. This decision is expected to slow both the deployment of large-scale solar farms in the United States and the rate of American solar job growth (which is 12 times faster than the rest of the economy). The tariff increases the cost of solar panels by about 10 to 15 cents per watt. That could reduce utility-scale solar installations, which have come in under $1 per watt, by about 11 percent.

The tariffs may lead China and other countries to appeal the move with the World Trade Organization. But could innovations in solar power compensate for tariffs on panels?

In my research, I have found that one solar technology – previously largely ignored because of low-cost photovoltaics, or PV, panels – could make a comeback: the humble mirror, or booster reflector, as it is known in the technical literature.

Capturing lost energy

Most engineering efforts to lower solar power costs are aimed at increasing the efficiency of solar PV cells, which increases the number of watts produced by a given panel under standard test conditions. This is normally good, but the advantage is reduced with large tariffs that raise the price of solar panels.

Working with a team in Canada, my group has shown that using mirrors to shine more sun on the panels can significantly crank up their output. The reflectors are placed opposite the solar panels to send more light toward the modules in front of them. The light that hits them is reflected back toward the solar panels to produce more electricity.

In a paper published in the Journal of Photovoltaics, we showed through simulations that a maximum increase of 30 percent is achievable for an optimized system.

We focused our research on the system rather than individual panels mostly because the current setup for ground-mounted solar panel arrays is wasting space and losing precious sunshine. The iconic flat-faced solar panels installed in large-scale (utility-scale) solar farms are spaced apart to prevent shading of the next row of panels.

In large-scale solar farms like this one at the Air Force Academy, project developers need to leave space between panels to prevent shading – area that could be partially filled with reflectors. Air Force Academy, CC BY

As the sun shines on the typical solar farm, sending electricity into the grid, a fair amount of the sun’s energy is lost as the light hits the ground between rows of panels. Past efforts have attempted to grow crops in this area between panels, a promising practice called agrivoltaics. Reflectors capture some of that lost energy from the sun.

Using CGI for solar simulations

Such booster reflectors, also known as mirrors or planar concentrators, are not widely used because of concerns about warranties. Normally, solar panels are warranted for 20 to 30 years under strict circumstances based on accelerated testing done by the manufacturers.

However, when putting more sunlight on the panel with a reflector, there are greater temperature swings and non-uniform illumination. Older simple optical simulations wrongly predicted the effect, which scared manufacturers about module failures. Thus, because of the uncertainty with potential hot spots, using reflectors often currently voids warranties for solar farm operators.

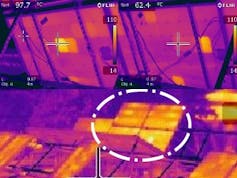

An infrared photo shows how reflectors send more light toward solar panels to produce more power. Joshua M. Pearce, CC BY-SA

We found a way to accurately predict the effects of reflectors on panels using bi-directional reflectance function, or BDRF, simulations. This phrase is a mouthful, but ironically most of us are used to seeing it used all the time. BDRF is regularly used in movies and video games to create more life-like computer generated imagery (CGI) characters and scenes.

This works for our purposes because BDRF equations describe how light bounces off irregular surfaces and predict how the light will scatter, creating indirect brightening and shadows. This is exactly what we needed to properly predict the impacts of non-perfect mirrors mounted in front of solar panels.

We created a BDRF model to predict how much sunlight would bounce off a reflector and where it would shine on the array. Real surfaces do not necessarily behave like perfect mirrors that perfectly reflect light, even if they look like it, so we applied BDRF models to these materials, which scatter the light instead.

The good news, we found, is that the ‘hot spot’ behavior was far less than predicted by simple optical models. By showing how the reflectors scatter light as a function of wavelength, we have started to take the risk out of using reflectors with solar panels, as well as show how the reflectors greatly increase solar system output.

Most importantly, we tested the model outside in a real array. We ran an experiment on Canada’s Open Solar Outdoors Testing Field in Kingston, Ontario.

The results were intriguing. We first tested reflectors with panels that were not titled in the optimal angle to capture solar energy for that location. With that placement and standard panels, the increase in generated solar electricity reached 45 percent. Even with a panel optimally tilted, the efficiency increased by 18 percent and simulations show it could be pushed to 30 percent with better reflectors.

Reflectors are not widely used by solar project developers now, in part because solar panels prices have come down so much. It has been typically cheaper and simpler to add more panels to an installation, rather than boost the output of panels by reflecting more light on them.

![]() But now with these tariffs, the solar industry may want to take a close look at reflectors again. A large increase of energy output at the system level by using mirrors could greatly change how solar panels are installed on solar farms, during this time of artificially inflated prices for panels coming from outside the U.S.

But now with these tariffs, the solar industry may want to take a close look at reflectors again. A large increase of energy output at the system level by using mirrors could greatly change how solar panels are installed on solar farms, during this time of artificially inflated prices for panels coming from outside the U.S.

Joshua M. Pearce, Professor, Michigan Technological University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.