Stocks prices are a proxy for our beliefs about the future

Courtesy of Joshua M Brown

One of the most aggravating things I’m forced to listen to from time to time is people citing widely available valuation ratios as though their very existence has some sort of meaning for the future price of a particular stock. Such and such company is selling for only 15x earnings, therefore it’s cheap and you should buy it.

One of the most aggravating things I’m forced to listen to from time to time is people citing widely available valuation ratios as though their very existence has some sort of meaning for the future price of a particular stock. Such and such company is selling for only 15x earnings, therefore it’s cheap and you should buy it.

This ignores the fact that any information available to the masses is already priced in and that markets, which are made up of hundreds of millions of participants, have settled on buying and selling a given security at its current price or valuation for a reason. Markets are very smart, which is not the same as saying they’re always right.

Such and such stock sells at 15 times earnings because, at the current moment, this is the equilibrium price at which sellers and buyers have reached a tacit agreement.

Citing a PE ratio is like remarking on the fact that it’s cold in Antarctica and hot in Africa.

What investors are really doing is attempting to divine the future prospects of a company and what they think it could someday be worth, and then placing their bets accordingly. Current valuations are useful in this endeavor only insofar as they present buyers and sellers with a an approximate baseline or a starting point.

And then from there, literally anything can happen.

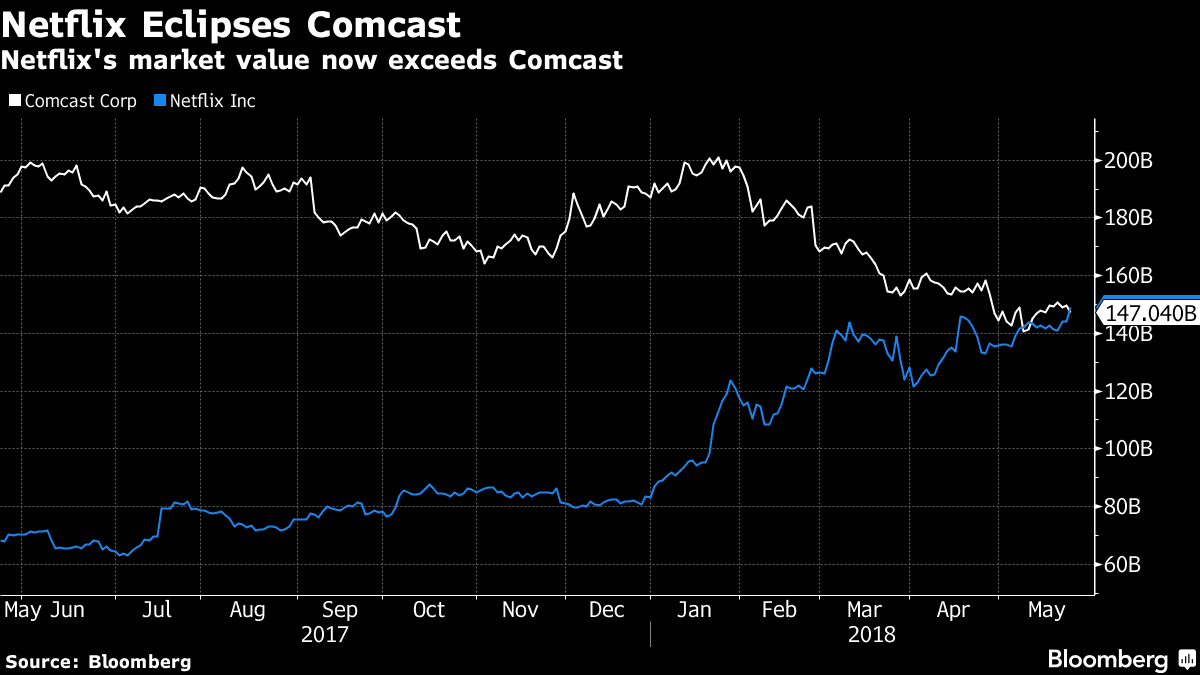

Netflix has just become the largest publicly traded media company in the country today, surpassing both content giant Disney and distribution giant Comcast in one shot. These securities are not being traded at their current levels because of ratio of price to current earnings. Rather investors and traders in both securities are making a bet on what the future looks like, incorporating possible risks to their forward-looking assessments and then either buying or selling depending on how far away prevailing prices are from their own individual guesses.

And then there are some other tangential considerations that go into this stew – optics (do I want to show my fund’s shareholders that I am in this name?), benchmarks (should I own more or less of these stocks than the index I am judged against), taxes (I have a huge gain, no sense in selling before it’s been at least a year), apathy (I hardly look at my stocks, just let them do what they do), short-termism (I’m up 10% this month, nobody ever went wrong taking a profit), peer pressure (everyone’s getting rich in that stock, I need some), exogenous reasons (I’ll sell here to pay for my daughter’s wedding), etc.

And this is before we add in all of the algorithmic buying and selling – activity that is utterly divorced from any sort of rhyme or reason and inhabits a digital realm of 1’s and 0’s. A game so completely impervious to your need for an explanatory narrative that no attempt to ascribe meaning to each day’s activity could ever, in a million years, bring you one iota of satisfaction.

If all this randomness, multiplied by all the guesses being made about the future, is too disorderly for you or its imprecision is offensive to your refined sensibilities, then this is not a game you ought to be playing. If the non-existence of a calculation or formula to slash through all of the considerations I’ve listed above is frustrating for you, then you should be aware that it has always been thus and it will never change. Surrender Dorothy.

The Netflix vs Comcast example is worth wrapping things up with…

Last year, Comcast did $85 billion in revenues and reported profits of $22 billion.

Last year, Netflix did $11.7 billion in revenues and reported profits of $550 million.

Both companies now have a market value of just under $150 billion dollars. Netflix has seen it’s market capitalization surpass Comcast, despite the fact that the latter company had roughly seven times higher sales last year and forty times profits.

And yet, here we are (chart via Bloomberg):

Both companies have announced big plans for 2018 and beyond, but investors have shown a clear and obvious proclivity to want to believe in Netflix’s future moreso than they do the future of Comcast. Whether investors are making a wise or a foolish bet is besides the point and entirely dependent on things that are beyond our ability to know in advance.

But what is not up for debate is whether or not the mere notice of a current valuation ratio is in any way determinant of what’s to happen with a given company’s share price.

Netflix has never been cheaper than Comcast. Comcast has never been more expensive than Netflix.

And yet the more expensive stock with substantially lower sales and earnings has gained over 30,000% since coming public over the last 16 years while the cheaper, more established company has gained merely 255% over the same period of time.

The recitation of a stock’s current valuation tells you absolutely nothing about its future price, but it tells you an awful lot about the prevailing sentiment around a company’s prospects. Stock prices are a proxy for our beliefs about the future.