Moderation in Infrastructure

Courtesy of Ben Thompson, Stratechery

It was Patrick Collison, Stripe’s CEO, who pointed out to me that one of the animating principles of early 20th-century Progressivism was guaranteeing freedom of expression from corporations:

It was Patrick Collison, Stripe’s CEO, who pointed out to me that one of the animating principles of early 20th-century Progressivism was guaranteeing freedom of expression from corporations:

If you go back to 1900, part of the fear of the Progressive Era was that privately owned infrastructure wouldn’t be sufficiently neutral and that this could pose problems for society. These fears led to lots of common carrier and public utilities law covering various industries — railways, the telegraph, etc. In a speech given 99 years ago next week, Bertrand Russell said that various economic impediments to the exercise of free speech were a bigger obstacle than legal penalties.

Russell’s speech, entitled Free Thought and Official Propaganda, acknowledges “the most obvious” point that laws against certain opinions were an obvious imposition on freedom, but says of the power of big companies:

Exactly the same kind of restraints upon freedom of thought are bound to occur in every country where economic organization has been carried to the point of practical monopoly. Therefore the safeguarding of liberty in the world which is growing up is far more difficult than it was in the nineteenth century, when free competition was still a reality. Whoever cares about the freedom of the mind must face this situation fully and frankly, realizing the inapplicability of methods which answered well enough while industrialism was in its infancy.

It’s fascinating to look back on this speech now. On one hand, the sort of beliefs that Russell was standing up for — “dissents from Christianity, or belie[f]s in a relaxation of marriage laws, or object[ion]s to the power of great corporations” — are freely shared online or elsewhere; if anything, those Russell objected to are more likely today to insist on their oppression by the powers that be. What is certainly true is that those powers, at least in terms of social media, feel more centralized than ever.

This power came to the fore in early January 2021, when first Facebook, and then Twitter, suspended/banned the sitting President of the United States from their respective platforms. It was a decision I argued for; from Trump and Twitter:

My highest priority, even beyond respect for democracy, is the inviolability of liberalism, because it is the foundation of said democracy. That includes the right for private individuals and companies to think and act for themselves, particularly when they believe they have a moral responsibility to do so, and the belief that no one else will. Yes, respecting democracy is a reason to not act over policy disagreements, no matter how horrible those policies may be, but preserving democracy is, by definition, even higher on the priority stack.

This is, to be sure, a very American sort of priority stack; political leaders across the world objected to Twitter’s actions, not because they were opposed to moderation, but because it was unaccountable tech executives making the decision instead of government officials:

I do suspect that tech company actions will have international repercussions for years to come, but for the record, there is reason to be concerned from an American perspective as well: you can argue, as I did, that Facebook and Twitter have the right to police their platform, and, given their viral nature, even an obligation. The balance to that power, though, should be the openness of the Internet, which means the infrastructure companies that undergird the Internet have very different responsibilities and obligations.

A Framework for Moderation

I have made the case in A Framework for Moderation that moderation decisions should be based on where you are in the stack; with regards to Facebook and Twitter:

At the top of the stack are the service providers that people publish to directly; this includes Facebook, YouTube, Reddit, and other social networks. These platforms have absolute discretion in their moderation policies, and rightly so. First, because of Section 230, they can moderate anything they want. Second, none of these platforms have a monopoly on online expression; someone who is banned from Facebook can publish on Twitter, or set up their own website. Third, these platforms, particularly those with algorithmic timelines or recommendation engines, have an obligation to moderate more aggressively because they are not simply distributors but also amplifiers.

This is where much of the debate on moderation has centered; it is also not what this Article is about;

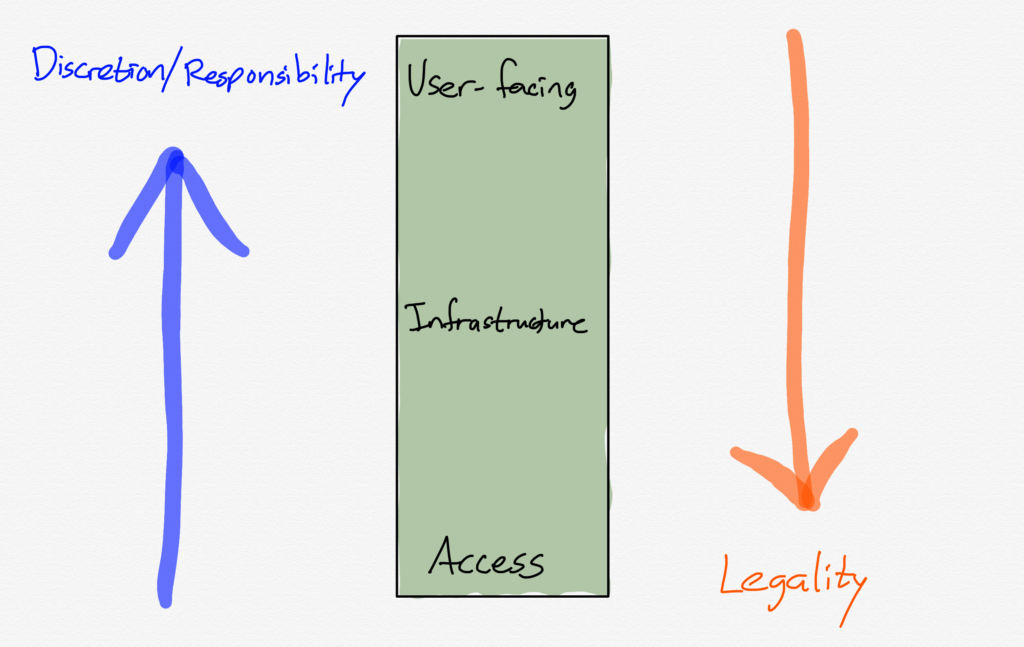

It makes sense to think about these positions of the stack very differently: the top of the stack is about broadcasting — reaching as many people as possible — and while you may have the right to say anything you want, there is no right to be heard. Internet service providers, though, are about access — having the opportunity to speak or hear in the first place. In other words, the further down the stack, the more legality should be the sole criteria for moderation; the further up, the more discretion and even responsibility there should be for content:

Note the implications for Facebook and YouTube in particular: their moderation decisions should not be viewed in the context of free speech, but rather as discretionary decisions made by managers seeking to attract the broadest customer base; the appropriate regulatory response, if one is appropriate, should be to push for more competition so that those dissatisfied with Facebook or Google’s moderation policies can go elsewhere.

The problem is that I skipped the part between broadcasting and access; today’s Article is about the big piece in the middle: infrastructure. As that simple illustration suggests, there is more room for action than the access layer, but more reticence is in order relative to broadcast platforms. To figure out how infrastructure companies should think about moderation, I talked to four CEOs at various layers of infrastructure:

- Patrick Collison, the CEO of Stripe, which provides payment services to both individual companies and to platforms. link to interview

- Brad Smith, the President of Microsoft, which owns and operates Azure, on which a host of websites, apps, and services are run. link to interview

- Thomas Kurian, the CEO of Google Cloud, on which a host of websites, apps, and services are run. link to interview

- Matthew Prince, the CEO of Cloudflare, which offers networking services, including free self-serve DDoS protection, without which many websites, apps, and services, particularly those not on the big public clouds, could not effectively operate. link to interview

What I found compelling about these interviews was the commonality in responses; to that end, instead of my making pronouncements on how infrastructure companies should think about issues of moderation, I thought it might be helpful to let these executives make their own case.