Why Job Numbers Are Always Revised — And Why We Can’t Know Them Instantly

By ChatGPT, prompted and edited by Ilene

Every month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) releases the headline jobs report, a key measure of how many jobs the U.S. economy has added or lost. These numbers drive news cycles, affect stock markets, and influence Federal Reserve policy. But what many people don’t realize is that these job numbers are estimates, and they are almost always revised in later months. Some find this confusing — even suspicious. Why can’t we just know the exact number of jobs immediately? And why do the numbers keep changing?

The answers lie in how job data is collected, why it takes time, and why revisions are a sign of accuracy rather than manipulation.

How Job Numbers Are Collected

The monthly jobs report is based primarily on two surveys:

-

The Establishment Survey (Payroll Survey)

This survey collects data from about 122,000 businesses and government agencies, covering around 666,000 worksites. It measures:-

The number of jobs (not workers)

-

Average hours worked

-

Average hourly earnings

This is where the “headline” number — for example, +73,000 jobs added in July — comes from.

-

-

The Household Survey

This smaller survey of about 60,000 households measures:-

Whether people are employed, unemployed, or out of the labor force

-

Demographic breakdowns (age, gender, race)

-

Part-time vs. full-time work

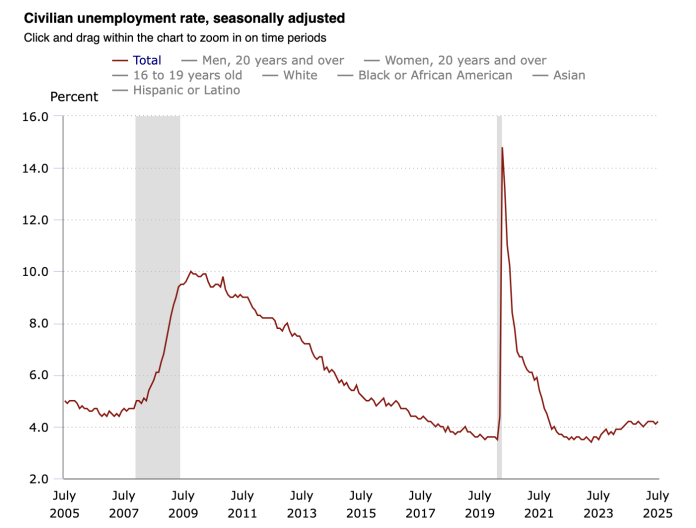

The unemployment rate (e.g., 4.2%) is derived from this household survey.

-

Why the First Report Is an Estimate

The challenge is time. The jobs report is released on the first Friday of each month, covering data from just a few weeks earlier. To meet this deadline, the BLS must publish its estimates before all survey responses are in. Usually:

- Only about 70–80% of businesses have responded when the first estimate is made.

- The BLS uses statistical models to fill in the gaps for non-responders.

- As more responses arrive in the following weeks, the BLS revises its numbers.

This is why initial reports sometimes show strong job growth, only to be revised up or down later.

Why Revisions Are Normal (Not Manipulation)

Revisions happen because:

-

Initial estimates are incomplete snapshots.

-

More responses arrive over time, leading to more accurate counts.

-

Statistical models used to fill in gaps get replaced with actual reported data.

Revision process:

-

First estimate: Released on the first Friday of the following month (e.g., July jobs reported in early August).

-

First revision: A month later, when more survey responses have been received.

-

Second revision: Two months later, after the response rate is close to complete.

These revisions can be significant, especially when economic conditions are changing quickly — as seen when recent estimates of 291,000 new jobs were revised down to just 33,000:

“This morning, the BLS released its monthly jobs report, showing that the economy added just 73,000 new jobs last month—well below the 104,000 that forecasters had expected—and that unemployment rose slightly, to 4.2 percent. More important, the new report showed that jobs numbers for the previous two months had been revised down considerably after the agency received a more complete set of responses from the businesses it surveys monthly. What had been reported as a strong two-month gain of 291,000 jobs was revised down to a paltry 33,000. What had once looked like a massive jobs boom ended up being a historically weak quarter of growth.” (The Mystery of the Strong Economy Has Finally Been Solved)

Why Not Use IRS Data to Speed Things Up?

At first glance, it seems reasonable: the IRS already has payroll data from employer tax filings, so why not just use that to count jobs? The reality is more complicated.

-

IRS Data Comes Too Late

Employers file payroll taxes (Form 941) quarterly, not monthly. W-2s, which list individual workers, are filed once a year. IRS systems are designed for tax collection, not real-time economic analysis. They process filings in batches, not in real time. By the time the IRS processes and verifies these forms, they are months old. -

IRS Forms Don’t Count “Jobs”

Payroll tax filings report total wages and taxes, not the number of employees on payroll in a specific month. A single person with two part-time jobs would show up twice, while a job lost mid-month might still appear as a full payroll entry. -

Legal Restrictions

IRS data is confidential under federal law. Even other government agencies, including the BLS, have limited access to raw IRS data. -

The BLS Does Use Tax Data — But Only Once a Year

The BLS performs an annual benchmark revision each February, comparing its survey results to state unemployment insurance tax records (which are based on employer filings, similar to IRS data). This ensures long-term accuracy, but it’s far too slow for monthly updates.

Why Revisions Are Not “Manipulation”

Some people see revisions as evidence that the numbers are being manipulated. In reality, revisions are the opposite: they reflect a commitment to accuracy.

Think of the monthly jobs report like a fast-moving snapshot — a best estimate based on partial data. As more information comes in, the snapshot becomes clearer. Revisions happen because:

- More businesses respond to the survey.

- Seasonal adjustments are refined.

- Late or corrected data replaces estimates.

This process is transparent and routine. Without it, the government would be relying on less accurate data.

Why We Can’t Have Instant Numbers

Even with modern technology, there is no way to get a real-time count of jobs because:

- Not all businesses report payroll data instantly.

- Employment isn’t static — people are hired and fired daily.

- Data must be verified to avoid double-counting or errors.

- The U.S. labor force is huge (around 160 million workers), spread across millions of employers. No single database can capture this in real time with 100% accuracy.

Real-time data would require:

-

Monthly or weekly tax filings from all employers.

-

A massive overhaul of IRS and BLS systems.

-

Legal and privacy changes to allow cross-agency data sharing.

While private payroll processors like ADP produce real-time job estimates based on their clients’ payrolls, these cover only a fraction of total employment and don’t fully capture government jobs, small businesses, or the self-employed.

The Tradeoff: Speed vs. Accuracy

The monthly jobs report is designed to give policymakers and the public a timely snapshot, even if it isn’t perfect. Over time, the annual benchmark revisions ensure that the jobs data aligns closely with tax and payroll records.

The Bottom Line

- We don’t get “instant” job numbers because payroll and tax data are delayed and not designed to measure employment in real-time.

- Revisions are not manipulation but rather a normal part of ensuring accuracy as more data arrives. (Sorry, Trump, firing the commissioner of the BLS, Erika McEntarfer, won’t change the numbers.)

- The BLS survey system, while imperfect, strikes a balance between speed, detail, and reliability.

Understanding these realities helps prevent overreactions to initial numbers and underlines why monthly reports are best viewed as part of a trend rather than a single definitive measure.