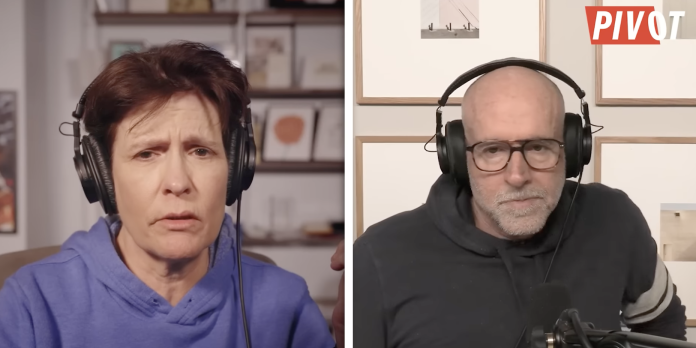

Kara Swisher & Scott Galloway’s 2026 Predictions on AI, Stocks, Trump, and… Lesbians?

Pivot with Kara Swisher and Scott Galloway, Pivot

Timeline

00:00 Intro and AI Predictions

6:32 Business Predictions

11:58 Politics Predictions

24:00 Media Predictions

33:00 Wildcard Predictions

Summary

In Kara Swisher and Scott Galloway’s annual predictions episode, Scott argues that 2026 is when the AI trade starts to look more fragile. His 2025 call that OpenAI and Nvidia would form a dominant duopoly largely played out, but he believes the next phase is about pressure, not dominance—especially pressure on OpenAI’s pricing power and on the broader AI investment thesis.

Scott argues that China, frustrated by tariff volatility and U.S. trade policy, could undercut U.S. AI economics by flooding the market with cheap, “good enough” AI models, particularly open-weight models. The goal wouldn’t be to beat the U.S. at frontier AI, but to make AI cheap enough that premium pricing and massive capital spending no longer look justified.

If that happens, the impact wouldn’t stop with AI companies. Scott believes it would ripple through the entire AI buildout trade—data centers, chips, power infrastructure—and force a rerating down of big tech valuations, which now make up an unusually large share of the S&P 500. In his view, faster AI commoditization is a key risk.

Kara Swisher’s counterpoint is that the real gains from AI won’t accrue to model makers, but to companies that combine AI with robotics and logistics—less humanoid robots, more embedded AI in manufacturing, warehousing, and mobility. Scott agrees, pointing to Amazon and Waymo as examples where AI shows up as operational leverage rather than a standalone product.

“AI Dumping”?

Scott is borrowing the concept of “dumping” from trade economics. Traditionally, dumping occurs when a country’s firms sell products into another market at very low prices, often supported by policy or subsidies, in order to take market share, weaken competitors, and create long-term dependence.

His argument is that China could apply this logic to AI. Not by shipping physical goods, but by releasing and promoting cheap, capable AI models—especially open-weight models—that companies can run themselves. This matters because most leading U.S. AI companies currently make money by selling access to their models through APIs.

An API (Application Programming Interface) is essentially a paid gateway. Instead of running AI themselves, companies send requests to a provider like OpenAI or Anthropic and are charged based on usage—primarily per token processed. This model functions like a utility: the more AI you use, the more you pay, and the more dependent you become on the provider’s pricing and terms.

Scott’s concern is that if firms discover they can get most of the AI capability they actually need without paying those ongoing API fees—by running open-weight models on their own servers or cloud infrastructure—the revenue foundation of the U.S. AI stack could start to look less secure. The technology still works, but the business model meant to pay for it weakens.

This matters because the market’s bullish AI story assumes that today’s massive spending on chips, data centers, electricity, and talent will eventually be justified by durable, high-margin rents from model access and enterprise lock-in. Scott’s concern is that if AI becomes abundant and inexpensive, those rents will become harder to sustain. Pricing power could erode, margins compress, and the return on enormous capital investment could become less certain—even if AI usage continues to grow rapidly.

The key here is open-weight models. Unlike closed systems where companies must pay every time they call an API, open-weight models let firms run AI on their own infrastructure, customize it for specific tasks, and switch providers more easily if better or cheaper options appear. That flexibility shifts bargaining power toward buyers. In software markets, it often takes only an alternative that’s “close enough” to force price competition. Scott captures this dynamic with a familiar rule of thumb: offer 80% of the leader at 50% of the price, and many customers will switch.

From an investment perspective, this doesn’t just threaten individual AI companies. Scott is worried about systemic exposure. AI-linked firms now make up a large share of major stock indices, and a significant amount of economic optimism rests on the assumption that AI will deliver sustained, high-margin profits. If investors begin to believe AI is becoming a commodity faster than expected, valuation multiples—not just earnings—would come under pressure.

Scott’s framing is strongest on the economic mechanism and weaker on coordination. Dumping usually implies a deliberate, sustained pricing attack. AI is more complex than manufactured goods: enterprises care about security, compliance, reliability, integration, and support, not just price. Running models at scale still costs money, and in sensitive or regulated industries, China-linked models may face adoption limits regardless of cost. There are also areas where top-tier performance materially changes outcomes, meaning “good enough” won’t replace everything.

Taken together, Scott’s thesis is less geopolitical than structural: open-weight models—including Chinese ones—could accelerate AI commoditization faster than markets expect, weakening pricing power for closed U.S. model vendors and making the returns on massive AI capital spending less predictable than current valuations assume.