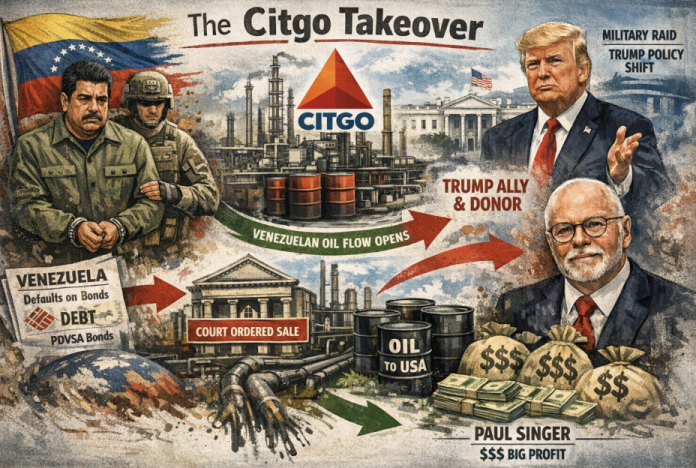

Venezuela raid enriches MAGA billionaire

The ouster of Maduro is a financial windfall for a prominent Trump-supporting billionaire, investor Paul Singer.

By Judd Legum, Popular Information

In a Saturday morning military raid ordered by President Trump, U.S. forces captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. After Maduro was apprehended and transported to New York to face criminal charges, Trump announced that the U.S. would “run” Venezuela for the indefinite future.

The extraordinary attack, which legal experts said violated U.S. and international law, created a financial windfall for a prominent Trump-supporting billionaire, investor Paul Singer.

How? Read more here >

UPDATE: Trump relaxes Venezuelan oil embargo, benefiting MAGA billionaire

By Judd Legum, Popular Information

On Monday, Popular Information reported [above] that the U.S. military raid that removed Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro from power could be a financial windfall for Paul Singer, a Trump-supporting billionaire.

Singer, through a company called Amber Energy, purchased Citgo, the U.S. subsidiary of Venezuela’s state-run oil company. The sale of Citgo was forced by creditors, including Singer, after Venezuela defaulted on billions in government-issued bonds.

Citgo owns significant oil refining capacity on the Gulf Coast of the United States and other assets. An advisor to the court that oversaw the sale estimated that Citgo was worth about $13 billion. But Singer was able to purchase Citgo for a substantial discount, $5.9 billion, because those refineries are purpose-built for Venezuelan heavy crude…

Summary

1. Big picture

The core claim is straightforward: Trump’s military removal of Venezuela’s president did not merely have geopolitical consequences—it unlocked enormous financial gains for a billionaire Trump ally who had just acquired Citgo at a distressed price.

2. Who Paul Singer is — and why his Trump ties matter

Paul Singer is the founder and controlling force behind Elliott Investment Management, a hedge fund with tens of billions of dollars under management and Singer’s personal net worth estimated at roughly $6–7 billion. Elliott is widely known for distressed-debt investing—buying defaulted or deeply discounted sovereign and corporate debt, then using litigation, arbitration, and aggressive legal enforcement to extract recoveries far exceeding the purchase price, often pursuing full face value plus interest and penalties. This approach has earned Elliott a reputation as a “vulture fund.”

Elliott’s strategy depends heavily on the power of U.S. and international courts. In past disputes involving countries such as Argentina, Congo, and Peru, the firm pursued governments for years, leveraging court judgments, asset seizures, and settlement pressure until payment was secured. Singer is not a passive participant in this model; he is closely involved in strategy and has long favored hard-line legal tactics over negotiated debt restructurings.

That legal leverage is what connects Singer’s financial interests to U.S. foreign policy. Elliott’s ability to enforce claims, seize assets, or unlock value from distressed investments is directly affected by sanctions regimes, Treasury licensing decisions, regulatory approvals, and executive enforcement priorities—areas where presidential authority and discretion are decisive.

Singer is also a major political donor. He contributed $5 million to Trump’s Super PAC, gave tens of millions of dollars to Republican congressional candidates aligned with Trump, helped fund Trump’s second presidential transition, and has met with Trump multiple times at the White House. After initially opposing Trump in 2016, Singer is now widely regarded as a fully aligned political ally.

That alignment matters because Trump’s actions toward Venezuela directly removed the constraints suppressing the value of Singer’s investment. Citgo’s refineries were purpose-built for Venezuelan heavy crude, but U.S. sanctions had blocked access to that oil, depressing profitability and valuation. Trump’s military removal of Nicolás Maduro and rapid relaxation of the oil embargo reversed that condition, restoring the very supply Citgo was designed to process. In effect, Trump’s policy choices did not merely shift geopolitics—they resolved the specific economic problem that had made Singer’s Citgo acquisition a distressed, bargain-priced deal.

3. The Citgo sale

Step 1: What bonds are we talking about?

Over many years, Venezuela issued both sovereign bonds and bonds through its state-owned oil company, PDVSA. These debts were sold to global investors, including pension funds, banks, and hedge funds. After Venezuela stopped paying, firms such as Elliott purchased large amounts of this debt at steep discounts.

Step 2: Venezuela defaulted

Beginning in 2017, Venezuela and PDVSA defaulted on billions of dollars in bond payments as the country’s economy collapsed amid mismanagement, declining oil production, and sanctions. A default is not merely financial stress; it is a formal failure to make required interest and principal payments. From that point forward, Venezuela made no comprehensive or voluntary effort to repay many of its creditors.

For investors like Elliott, this default transformed a financial investment into a legal claim. Bondholders became creditors and turned to U.S. courts and international arbitration to enforce judgments and seek compensation from Venezuelan-owned assets abroad.

Step 3: Why Citgo got pulled into this

Citgo is Venezuelan-owned but incorporated in the United States. As a result, its assets fall under U.S. jurisdiction and are reachable by U.S. courts. Creditors successfully argued that if Venezuela refused to pay its debts, Venezuelan-owned assets located in the United States could be seized to satisfy those claims.

Step 4: How the forced sale worked

A U.S. court approved a judicial auction of Citgo to convert the company into cash. The proceeds would then be distributed to creditors holding valid legal claims. Singer, through Amber Energy—an Elliott subsidiary—won the auction with a $5.9 billion bid.

Step 5: Did creditors get paid?

Yes—partially. The sale proceeds are earmarked to pay court-approved creditors according to a priority order set by the court. Not all creditors are treated equally, and most recover far less than the face value of their original bonds or arbitration awards. The sale converts a complex web of unpaid claims into a finite pool of cash, distributed after legal and administrative costs.

Elliott’s profit likely came from purchasing Venezuelan debt at deep discounts during default and then using litigation and court enforcement either to recover cash from the sale proceeds or to convert debt claims into ownership or control leverage over Citgo.

Crucially, Venezuela did not repay these debts voluntarily. No negotiated settlement occurred. The payments came from the seizure and forced sale of a Venezuelan-owned asset.

4. Why Trump’s actions supercharged Singer’s deal

Before the change in U.S. policy, Citgo’s business was structurally impaired. Although its refineries were engineered to process heavy Venezuelan crude, U.S. sanctions blocked access to that oil. Citgo was therefore forced to purchase heavier crude from alternative sources such as Canada and Colombia, which was more expensive and often less compatible with its infrastructure. That mismatch squeezed margins and depressed profitability, contributing to Citgo’s discounted sale price.

That dynamic shifted rapidly after Trump’s actions. By removing Maduro, loosening the Venezuelan oil embargo, and directing tens of millions of barrels of Venezuelan crude to U.S. ports, the administration restored the supply Citgo’s refineries were designed to handle. With access to cheaper, compatible crude, Citgo could operate as intended. The market response to similar refiners underscores the impact: companies like Valero, which also operate Gulf Coast refineries optimized for heavy crude, saw sharp valuation increases following the policy shift.

The implication is clear: Trump’s policy choices resolved the precise economic constraint that had made Citgo a distressed, bargain-priced asset.

5. Why critics see this as a conflict problem

A major Trump donor purchased a distressed Venezuelan asset. Trump then used military force and sanctions authority in ways that dramatically increased the asset’s value. The same donor stands to gain billions.

Even absent explicit coordination, critics argue this creates the appearance that U.S. military and foreign-policy power is enriching politically connected investors.

Bottom line

Paul Singer, a hedge fund billionaire and major Trump ally, acquired Citgo—Venezuela’s U.S.-based refining arm—at a steep discount after Venezuela defaulted on government and oil-company bonds. The forced sale occurred through U.S. courts, with proceeds flowing to creditors like Singer rather than to Venezuela itself. Citgo was cheap largely because U.S. sanctions blocked access to Venezuelan oil, crippling its refinery economics. Trump’s removal of Maduro and rapid reopening of Venezuelan oil flows reversed that constraint, sharply increasing Citgo’s value. The article argues that this sequence transformed Trump’s foreign policy into a financial windfall for a politically connected investor.