Willem H. Buiter writes an excellent, philosophical article examining the tension between our fundamental rights as human beings and the power of government, which by its nature limits those rights. Finding that the cost of freedom is eternal vigilance against the power of the state, Willem concludes that, not unimportantly, the preservation of freedom may have more to do with government incompetence than with a well-built system of checks and balances. – Ilene

In praise of government incompetence

Courtesy of Willem H. Buiter, at the Financial Times’ ft.com/maverecon

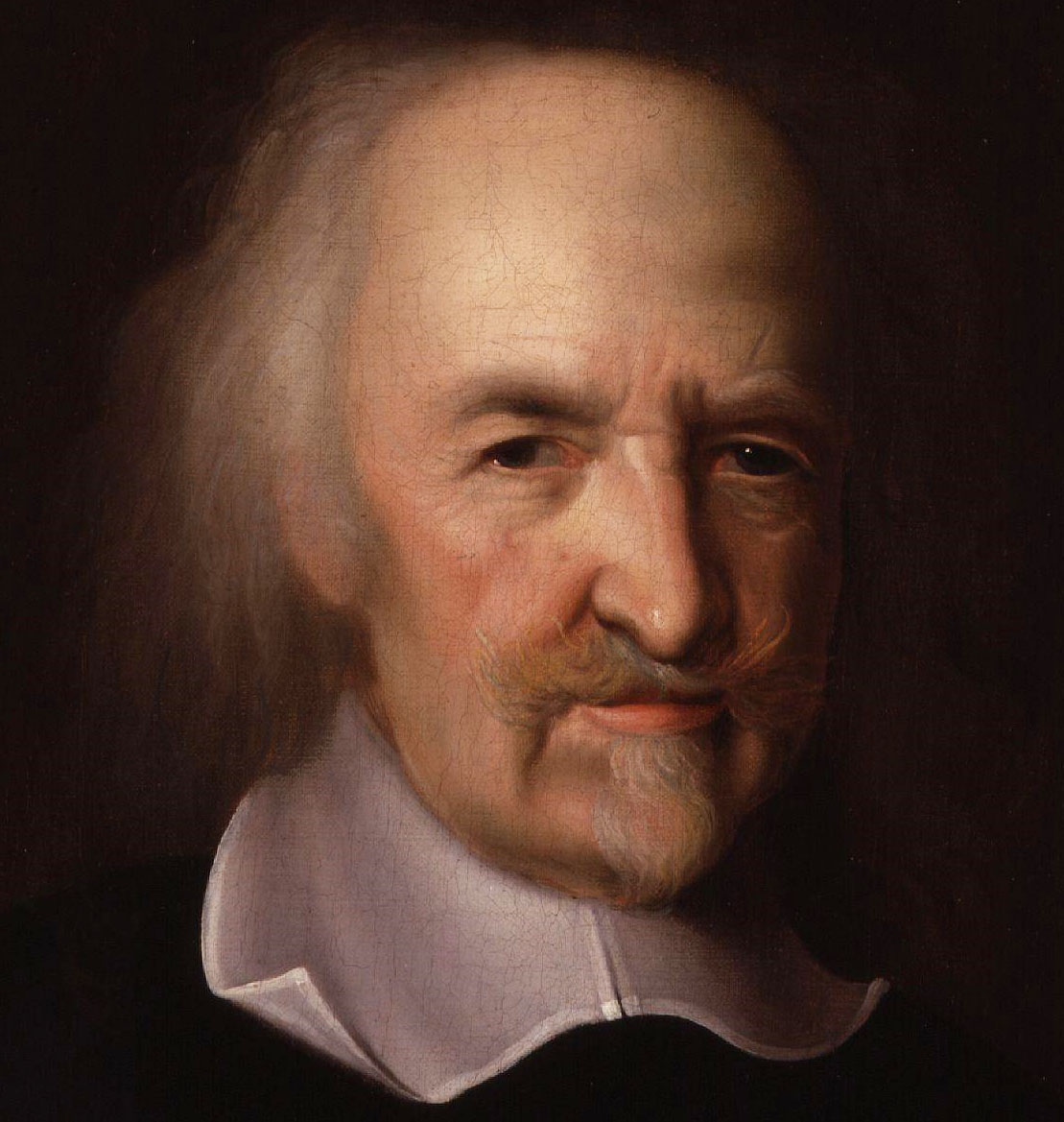

A monopoly is a bad thing. It invites abuse of the power it controls. Sometimes it is not the worst thing that could happen. Anarchy or the ’state of nature’, can be worse. I don’t know whether Thomas Hobbes was right for all time and places in asserting that man is not by nature a social animal and that society could not exist except by the power of the state – the wielder of the monopoly of legitimate coercive power.

There may have been some bucolic, idyllic communities that dispensed with the institution of the state, where the fundamental rights of people (life, health, liberty) and property rights could be enforced effectively by individual action or through acts of spontaneous cooperation without external, third-party enforcement. But once we get to communities exceeding a dozen or at most a gross of people, an institution endowed with the monopoly on the legitimate use of force against its own citizens appears to have evolved, to have been created or to have been imposed everywhere.

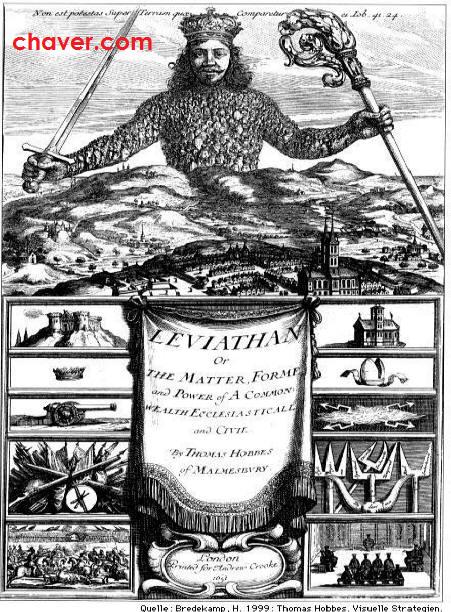

From Chapter 13 of The Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes’s rhetoric in making the case for the state in human affairs, is magnificent : “Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of war, where every man is enemy to every man, the same consequent to the time wherein men live without other security than what their own strength and their own invention shall furnish them withal. In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

As positive descriptions, that is, characterizations of what is likely to happen without a minimally effective state, rather than of what ought to happen, I much prefer Hobbes to Locke. However, as a normative characterisation of what ought to be in the state of nature, and of how the institution of government and the state can be made to serve the interests and rights of man, I’m with Locke.

According to Locke, “The state of Nature has a law of Nature to govern it”, and that law is Reason. Reason teaches that “no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty or possessions”. When attempts by individuals to prevent or punish transgressions of natural law are ineffective, a limited and restricted role for government emerges ‘naturally. Locke’s view of the state of nature is in part motivated from his Christian belief: the reason we may not harm another human being is that we are all God’s children, and therefore the possessions of God. We do not own ourselves.

The fact that we grant the state (and the government in charge of the instruments of the state) a normative raison d’être and acknowledge the universality of its presence in every historical organised human society, does not mean we should respect, let alone trust the state. The state is a necessary evil. It is necessary for the reasons outlined by Hobbes, Locke and many other worldly philosophers. It is evil because I know of no example of a state that has not abused its power over its citizens. Nor do I know of a society where the state does not try to extend its control over the lives of the citizens to domains that are none of its business and that are not material to the performance of the key tasks of the state. Every action, legislative initiative, executive order, legal ruling or administrative decision must therefore be scrutinised with the eyes of a hawk and with a deep and abiding mistrust of both the motivations and the likely consequences of any state action or initiative. The simple rule of thumb as regards both new and existing laws, rules and regulations should be: when in doubt, throw it out.

Every restriction on our liberties – our right to speak, write, criticize and offend as we please, to act and organize in opposition to the government of the day, to embarrass it and to show it up by forcing it to look into the mirror of its own leaked secrets – must be resisted. We cannot afford to believe any government’s protestations that it is acting in good faith and will safeguard the confidentiality of any information it extracts from us. Public safety and national security are never sufficient reasons for restricting the freedom of the citizens. The primary duty of the state is to safeguard our freedom against internal and external threats. The primary duty of an informed citizenry is to limit the domain of the state – to keep the government under control and to prevent it from becoming a threat to our liberties.

The threat posed by our own government to our liberty and fundamental rights is a constant one. Most of the time it is a much greater, direct and immediate threat than that posed by foreign states (through conquest or extortion) or by external non-government agents, the violent NGOs like Al Qaeda.

In a limited number of countries a fair degree of personal and political freedom has been achieved during the past three or four centuries. I have been fortunate to always have been a resident in this blessed corner of the universe – in the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Belgium, the United Kingdom and the United States. I have, however, visited many countries where these freedoms never took hold or took hold but briefly and have been whittled away again.

I have become convinced that the price of freedom is eternal vigilance against the encroachment by the powers of the state on the private domain. The better-intentioned a government professes to be, and the better-intentioned it truly is when it first gains office, the more it is to be distrusted.

After even the most liberal-minded, open-government-committed party takes hold of the reins of government, it takes never more than a single term of office, four years – five at the most – before paranoia takes over. Disagreement becomes dissent, dissent becomes disloyalty, disloyalty becomes betrayal and betrayal becomes treason. The public interest merges seamlessly with the private interest of the incumbents. The state bureaucracy, where it has not been taken over by government loyalists on day one of the new administration, is gradually transformed into an arm of the government. Some formal checks and balances often remain, parliament and the courts among them, but they too are often feeble to begin with and weaken further as the term office of the incumbent government lengthens.

I have watched this process at work in the UK since I returned here in 1994. It was breath-taking and depressing to observe the transformation of New Labour after 1997, from the party of open government, human rights and civil liberties into an increasingly paranoid group of power-hogging and repressive political control freaks, who have done more damage to fundamental human rights in the past 11 years than any other (sequence of) government(s) in any comparable-length stretch of time since the Glorious Revolution. Fortunately, despite their worst intentions, they have not been very competent – a more competent government could have done much more damage to our freedom and civil liberties.

The price of freedom may be a weaker and less efficient state than a conventional utilitarian cost-benefit analysis would dictate. That is not surprising, as utilitarianism leads to paternalism (possibly with a detour via libertarian paternalism – the latest political oxymoron), and paternalism leads to authoritarianism and ultimately to totalitarianism as surely as the statement: “I’m from the government and I am here to help you”, will before long be followed by “and I know what is good for you, and for society at large – so up against the wall, you ….”.

It is not possible, I believe, to have ’strong but limited’ government or ‘efficient and effective but restricted, bounded and confined’ government. The reason is that the same capabilities that make a government (as the manager of the state) strong, efficient and effective in the the pursuit of set tasks and objectives, will also drive that government to increase the scale and scope of its ambitions and the degree of control it exercises over every aspect of our lives.

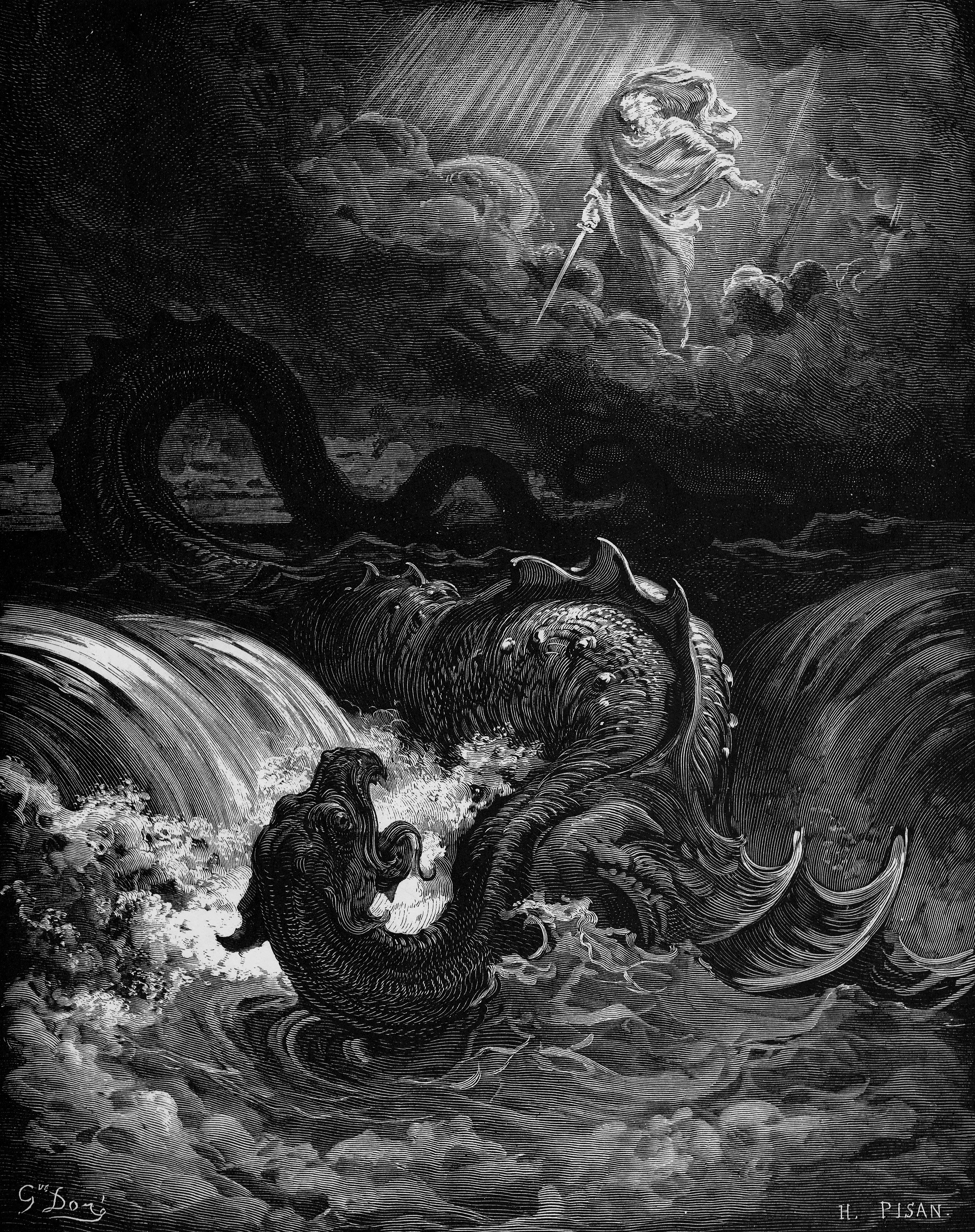

The historical-institutional processes that drive the evolution of the state are quite likely to result in an all-absorbing Leviathan. This is because the main actors competing for the control of the government and thus of the apparatus of the state are recruited by political processes that select for people with a hunger for power, ruthlessness, a belief that the ends justify the means and an unquestioned faith that the common good (as seen by the aspiring politico) always takes precedence over individual rights and liberties. We have to hobble this would-be Leviathan if we value what is left of our rights and liberties.

In the UK, restoring the power of parliament, badly eroded by the demise of the House of Lords as a serious upper chamber, would be a step towards restoring checks and balances, especially if the new upper chamber could be elected by proportional representation. Cleaning up the incomprehensible structure of the UK judiciary, with some members of the judiciary cropping up in parliament and others in the executive, is also long overdue. A written, modern Bill of Rights would also help to redress the balance of power between the overweening executive and the rest – the timid, gutless and toothless parliament, the emasculated judiciary and the disenfranchised electorate.

But I doubt whether any of this will be enough to safeguard our freedom. Fortunately we have one firm ally: government incompetence and ignorance.

So whenever I come across yet another egregious example of government inefficiency (be it waiting since 1989 for work on Cross Rail to start, another laptop with confidential information left on the train, interminable blockages of major access roads by non-synchronized excavations arranged by the electric power company, the gas company, the phone company, the cable TV company and the maintainer of the Greater London drains, or unsuccessful attempts to have a broken water mains repaired during a period when an Official Drought Order was in effect) I feel strangely uplifted. A government and a state apparatus that cannot punch their way out of a wet paper bag when it comes to so many important and useful things may not be able to mount much of a threat to our freedom and civil liberties after all.

The price of freedom is government inefficiency. An ignorant and uninformed state is the corner stone of liberty. Constitutional reform designed to limit the competence of the government and the quantity and quality of the information it has at its disposal should figure prominently in the next Queen’s Speech.

*******

About Willem H. Buiter: Professor of European Political Economy, London School of Economics and Political Science; former chief economist of the EBRD, former external member of the MPC; adviser to international organisations, governments, central banks and private financial institutions.