The Case Against Goldman Sachs

By Stephen Gandel, courtesy of TIME

The biggest bummer to arise from the allegations that the revered and feared Wall Street puppet master Goldman Sachs had played us all for patsies is this: the dial on the Wall Street capital-formation machine, the engine that was supposed to be the driving force of the greatest economic system on earth, was purposely set to junk — worthless, synthetic junk.

The civil fraud case the Securities and Exchange Commission filed in mid-April against Goldman is based on a single deal, called Abacus 2007-ac1. The investment bank created it so hedge funder John Paulson could line his pockets with cash when the value of American families’ most prized asset crashed. But on Wall Street in the late aughts, polyester financing was in fashion everywhere.

.png) Morgan Stanley had the so-called dead-Presidents deals, named Buchanan and Jackson. Another Morgan deal, one called Libertas, defrauded investors in the U.S. Virgin Islands, according to a lawsuit. JPMorgan Chase played procurer for Magnetar, a hedge fund so artful in profiting from the meltdown that Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management praised it last year in a case study. A firm run by Lewis Sachs, until recently a top Treasury Department adviser, and UBS, until recently a tax-cheat favorite, created junky bonds that investors who bought them now claim were going bad even before the deals were closed. Bank of America too is being sued for a deal that was set up by its Merrill Lynch subsidiary with a manager who is now under investigation by the SEC.

Morgan Stanley had the so-called dead-Presidents deals, named Buchanan and Jackson. Another Morgan deal, one called Libertas, defrauded investors in the U.S. Virgin Islands, according to a lawsuit. JPMorgan Chase played procurer for Magnetar, a hedge fund so artful in profiting from the meltdown that Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management praised it last year in a case study. A firm run by Lewis Sachs, until recently a top Treasury Department adviser, and UBS, until recently a tax-cheat favorite, created junky bonds that investors who bought them now claim were going bad even before the deals were closed. Bank of America too is being sued for a deal that was set up by its Merrill Lynch subsidiary with a manager who is now under investigation by the SEC.

In the end, it was in fact all one big scam predicated on rising housing prices. Certainly, greedy consumers played a minor role in feeding the frenzy. But the Street made sure that those of us who are not members of its elite club remained the suckers.

Why didn’t we find out about these deals sooner? Because they were encapsulated in one of Wall Street’s most opaque investment creations ever: synthetic collateralized debt obligations, or CDOs. Synthetic CDOs are derived from mortgage bonds — hence they are derivatives — but they don’t actually hold assets, although you can invest in them as you would in the real thing. And you can also short them, as you would a stock, using insurance contracts called credit-default swaps, or CDSs. In the Goldman case, the investment banks and hedge funds that concocted the CDOs allegedly loaded them with the equivalent of toxic bonds and then bought CDSs for themselves, figuring the CDOs would lose value. They did, which left the unsuspecting investors and counterparties who swallowed the CDOs — including supposedly sophisticated banks such as the Netherlands’ ABN Amro Bank and Germany’s IKB — wondering what happened to their money.

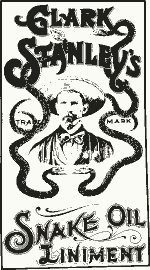

On the surface, these deals look complicated. They are. But the alleged fraud at the heart of the case against Goldman and its CDO dealings is one of the simplest and oldest forms of deception: lying. According to the SEC, Goldman told one group of investors they were buying a AAA-rated (by lapdog ratings agencies, but that’s another story) high-yield investment put together by an independent firm called ACA Management. But the SEC says the person really picking the collateral was Paulson, an investor whose only interest was: Paulson. What Goldman allegedly sold, like any good snake-oil salesman, was a worthless, well-packaged fake.

On the surface, these deals look complicated. They are. But the alleged fraud at the heart of the case against Goldman and its CDO dealings is one of the simplest and oldest forms of deception: lying. According to the SEC, Goldman told one group of investors they were buying a AAA-rated (by lapdog ratings agencies, but that’s another story) high-yield investment put together by an independent firm called ACA Management. But the SEC says the person really picking the collateral was Paulson, an investor whose only interest was: Paulson. What Goldman allegedly sold, like any good snake-oil salesman, was a worthless, well-packaged fake.

Only now, in the wake of the SEC suit against Goldman, are investors beginning to suspect they were hoodwinked. According to Thomson Reuters, Wall Street firms underwrote at least $119 billion worth of these deals as the housing market began to crumble, from 2006 until the music stopped. And this number could be low. Many of these deals never get counted, because they are private transactions and not traded on an exchange.

All the firms that set up these deals, and the hedge funds that bet against them, contend they did nothing wrong. A synthetic CDO is at its core a trade, meaning it has a long and short position, and grownup investors are free to take sides. In response to the SEC suit, Goldman says it didn’t set up investments to fail and it didn’t mislead its clients. It plans to fight the charges aggressively. Some have even argued that these synthetic deals were good for the economy, because they didn’t boost lending at a time when the housing market was already overheated. The reality is that Wall Street’s CDO synthesizer set one of the economy’s largest sectors off in the direction of creating nothing but waste — pure economic waste. These CDOs didn’t help anyone afford a house. No cars were purchased. No one got a loan to go to college. These CDOs were the last stop in a vast transfer of wealth from a large group of American mortgage holders to a much smaller group of already rich traders who profited as the CDOs failed.

Certainly, the folks who lied to get mortgages, and the banks who helped them, deserve what they get. Still, as most of us worked hard to cobble together a down payment for a house in an ever rising market or put money into our still-damaged-from-the-dotcom-bust investment accounts in order to send our kids to college or retire, we assumed the financial system was working its invisible magic to help make all that possible. In fact, just the opposite was going on. Wall Street was busy chartering buses to nowhere, so our jobs and savings could be driven right out of town.

How the Culture Changed

It is easy to think that Wall Street has always been the place for the corrupt and the greedy and that this is nothing new. But that’s not really accurate. Of all the causes of the financial crisis, one of the biggest was a power shift on Wall Street that left the traders in charge and the bankers who had traditionally run everything from Broad Street to Maiden Lane sidelined.

Years ago, the investment world and its professionals believed in long-term relationships. That meant nurturing the economy and the companies and people in it. Two decades of cheap money, though, helped turn the Street over to the traders. That led to a very different way of doing business. "With a trader, the goal of every minute of every day is to make money," says Philipp Meyer, who worked for UBS as a trader in the late 1990s and early 2000s before going on to write about his time there. "So if running the economy off the cliff makes you money, you will do it, and you will do it every day of every week."

Years ago, the investment world and its professionals believed in long-term relationships. That meant nurturing the economy and the companies and people in it. Two decades of cheap money, though, helped turn the Street over to the traders. That led to a very different way of doing business. "With a trader, the goal of every minute of every day is to make money," says Philipp Meyer, who worked for UBS as a trader in the late 1990s and early 2000s before going on to write about his time there. "So if running the economy off the cliff makes you money, you will do it, and you will do it every day of every week."

The question is, now that we know what we know about what has become of Wall Street, what do we do about it? The SEC case against Goldman shows that the agency plans to do more to combat fraud. That’s a big change. Under former commissioner Christopher Cox, Wall Street was basically self-regulating and the SEC hands-off, which helped enable the greatest Ponzi schemer of all time, Bernie Madoff.

By picking a fight with Goldman — the "great white whale" of Wall Street, as Eliot Spitzer put it on Monday — the SEC is signaling that it has now adopted a feistier approach. "Goldman got picked out because of its stature. When you take on the biggest kid on the block, you are sending a message to everyone on Wall Street that we’re not going to back down," says Peter Henning, a former SEC attorney and a professor at Wayne State University Law School. "It’s a very aggressive tactic, and in some ways it breaks with past practice."

So, in fact, does the way Goldman is being run. Perhaps the best illustration of the shift on the Street is the career of Goldman’s chief executive, Lloyd Blankfein. Back in 1982, when Blankfein, now 55, joined Goldman with a law degree from Harvard and a few years’ experience as a tax attorney, the firm was run by two investment bankers, John Whitehead and John Weinberg. Blankfein landed a job in the firm’s commodities-trading unit, which Goldman had acquired less than a year before.

Goldman was pretty typical of Wall Street in the 1980s. Investment bankers ran the business and brought in most of the bucks. Salesmen and brokers did pretty well too, buying and selling stocks for clients. Traders, who placed bets with the bank’s money, were generally the low men on the totem pole. The one exception was Salomon Brothers, where a band of traders led by Lewis Ranieri — who were raking in money trading Treasury and mortgage bonds — were quickly making Solly the beast on the Street. At Lehman Brothers too, trader Lewis Glucksman forced out investment banker Pete Peterson, who had been running the firm. But a scandal caused Salomon to flame out in the early 1990s. Trading losses at Lehman nearly bankrupted the firm and pushed it into the arms of American Express. Then Long-Term Capital Management nearly brought down the financial system in 1998 when some of its highly leveraged trades collapsed. After an all-hands rescue, the order of Wall Street was restored, temporarily.

At Goldman, Blankfein was rising rapidly by taking more and more risks in its commodities- and currency-trading businesses. In 1995, shortly after he was named head of the firm’s commodities business, he reportedly left a meeting of Goldman partners after complaining the firm was not taking enough risks and immediately bet multimillions of Goldman’s capital that the dollar would rise. It did, and Blankfein and Goldman made a bundle.

Yet during the 1990s, trading remained a side business for Wall Street. The cash cow was equities and, in particular, initial public offerings (IPOs), for which bankers were paid a sweet 7% of the deal for little more than ushering new companies into the market and at very little risk. In 1998, the year before Goldman went public, just 28% of its revenue came from trading and principal investments. By 2009, it was 76%.

The big change on Wall Street and at Goldman came with the collapse of the dotcom bubble in early 2000. The underwriting and mergers-advisory businesses on which the investment banks had minted money dried up completely. It would be years before the M&A market came back. IPOs never really did. Where was money being made? In trading. Low interest rates following the early-2000s recession made borrowing cheap. That pushed profits in trading, a capital-intensive business, to take off. Firms began shifting more capital to their trading desks. In the first half of the decade, Goldman’s so-called value at risk, which measured how much the firm was risking in the market each day, zoomed from an average of $28 million in 2000 to $70 million in 2005.

Traders, aided by a new generation of Ph.D.-type rocket scientists trained in the complex math of higher finance, began refocusing their firms on the products that would make them the most money. One of the most popular of the new bunch was the CDO. As with everything else on Wall Street, the rise of the CDO had to do with bonus checks. Traders’ pay was based not just on how much money they made for the firm but on the size of the bet. Turn in a $10 million gain on AAA Treasurys and you got paid a lot more than if you made the same amount trading lower-rated, much riskier junk bonds. The problem was that making big bucks in the well-established Treasury market was nearly impossible. It’s too transparent.

As a trader, what you needed was to take a market in which bonds were thinly traded and magically fill it with more-tradeable highly rated AAA material. By the magic of CDOs you could do just that. CDOs are often created out of the lowest-rated, seldom-traded portions of other bond offerings. And by the mid-2000s most of those bonds were backed by home loans to borrowers with poor credit ratings — toxic waste, in the parlance. Subprime-mortgage bonds went into the CDO blender BBB and came out AAA. All of a sudden, traders were making big money.

With the money came promotions. In 2005, bond salesman John Mack took the reins of Morgan Stanley, promising to boost the firm’s profits by allowing its traders to dial up risk. At Lehman Brothers, Dick Fuld, who had climbed that firm’s bond-trading ranks, was firmly in place as CEO. And in 2006, when Goldman’s CEO, Hank Paulson, a classic investment banker, was tapped by President Bush to be the Treasury Secretary, Blankfein was named as his replacement. The traders had won. "The industry became so heavily weighted toward risk, it just made sense to let the traders run things," says top Wall Street recruiter Gary Goldstein, who heads up the Whitney Group.

Or so it seemed. Traders got Wall Street firms deeper and deeper into more and more complicated products. Complexity, of course, can beget chicanery. Traders were too often in it to make a killing and an exit and cared little about the hazards they might be creating down the road. The term IBG, YBG became popular on the Street. It stands for "I’ll be gone, you’ll be gone"; someone else will have to clean up the mess.

Goldman boss Blankfein is an alpha dog in this pack. He hails from Wall Street’s roughest neighborhood, the commodities-trading market, which lacks insider-trading rules and many of the other investor protections of other markets. "In the commodities-trading market, when someone is stupid, that’s something to be taken advantage of," says Susan Webber, who under the name Yves Smith is the author of ECONned, a book about the financial crisis. "That’s the world Blankfein grew up in."

Goldman’s Alleged Duplicity

The idea that a 20-something trader with too much power could torpedo the biggest, most profitable firm in finance seems like a plot for a Wall Street parody. But it appears to be exactly what is happening to Goldman, and it is perhaps the logical end of a culture that anointed traders king. In late 2006, Fabrice Tourre, a then 27-year-old Frenchman who had graduated from Stanford’s business school in 2001 before joining the firm, got an assignment to help John Paulson place bets against the housing market.

Tourre, known to refer to himself as the "fabulous Fab," figured out how to structure an investment that was sure to suck the last bit of blood out of the few mortgage investors willing to buy into a market that he believed was due to crater. As Tourre was assembling Paulson’s CDO in January 2007, he wrote in an e-mail to a buddy: "The whole building is about to collapse anytime now … Only potential survivor, the fabulous Fab … standing in the middle of all these complex, highly leveraged, exotic trades he created without necessarily understanding all of the implications of those monstruosities [sic] !!!"

What Tourre did understand, according to the SEC, was how to trick investors. The SEC case against Tourre and Goldman hinges on the investment bank’s omission of the fact that Paulson was selecting most of the assets for Abacus. Tourre got the CDO manager, ACA Management, to claim in the offering statement that it had picked the assets for Abacus. ACA was getting paid to act as independent manager of the deal. The SEC alleges that while ACA understood that Paulson would have sway over asset selection, Tourre maneuvered ACA into thinking that Paulson planned to invest in Abacus, not bet against it. Paulson was never mentioned in the information sent to Abacus investors and Goldman’s counterparties, who ended up losing $1 billion on the deal.

For its part, Goldman vigorously denies the charges, arguing it did not structure the portfolio to lose money — in fact, the firm says it lost more than $90 million through its long position — nor did it misrepresent Paulson’s short position. "The SEC’s complaint accuses the firm of fraud because it didn’t disclose to one party of the transaction who was on the other side of that transaction," Goldman said in a press release. "As normal business practice, market makers do not disclose the identities of a buyer to a seller and vice versa. Goldman Sachs never represented to ACA that Paulson was going to be a long investor."

In a sense, Goldman is relying on the so-called big-boy defense: There are no victims on Wall Street, just fools. "This is no slam dunk for the SEC," says Henning. "We want every transaction to be fair, but these aren’t babes in the woods that got taken. These are two banks [that] invested in a very risky area and got very badly burned … That’s how free markets work. You take your chances."

Making the Case for Regulation

The Goldman case may be the opening salvo as a suddenly muscular SEC takes a gander at other Abacus-like deals. Like Goldman, Deutsche Bank struck deals with Paulson, according to the Wall Street Journal, that were structured to bet against the housing market. Magnetar and Tricadia are also in the spotlight, but even if the two hedge funds played their deals to fail, the investment banks that set them up at least disclosed the role of the hedge funds and the fact that they could take a short position.

Beyond any legal issues, the Goldman case has become the battering ram for financial-reform legislation that congressional Democrats have been looking for. Democrats say it underscores the need to reregulate an industry gone wild. Republicans retort that the reforms on the table would have done little to stop the Goldman trade. The latter point is probably right, at least in part. The bill sponsored by Democratic Senator Christopher Dodd would require transactions like Abacus to be traded on an exchange. Such transparency would give the SEC and other regulators more access to monitor these deals and potentially catch material misstatements. The SEC might have noticed earlier the obvious conflicts of interest inherent in the Abacus-like deals. But there still would have been no way for the SEC, without an investigation, to have known that Goldman was omitting any mention of Paulson’s involvement.

Nonetheless, the Goldman case does get the Obama Administration back on its best talking points for financial reform: The lack of regulation has morphed Wall Street into a place that regularly trades against our economy. It’s our jobs vs. their bonuses on every trade. And if you think Wall Street is going to protect your interests, then I’ve got a AAA-rated, subprime-mortgage-based CDO to sell you.

— With reporting by Alex Altman / Washington

Second and forth pictures from the top, courtesy of Jr. Deputy Accountant