Courtesy of John Rubino.

It’s amazing what you can get used to if it just goes on long enough. Everyone with a family has experienced this personally, but it’s also true at the societal level, where one decade’s impossibility becomes the next’s normal. Not so long ago, for instance, interest rates signified the amount by which a bank CD or bond would increase your wealth each year. But today’s rates are so low that most fixed income instruments are now functionally the same as a checking account, simply a place to park your spare cash until you need it – not an investment that will grow with time. Zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) has created a depressing, in some cases impoverishing “new normal” for savers and retirees.

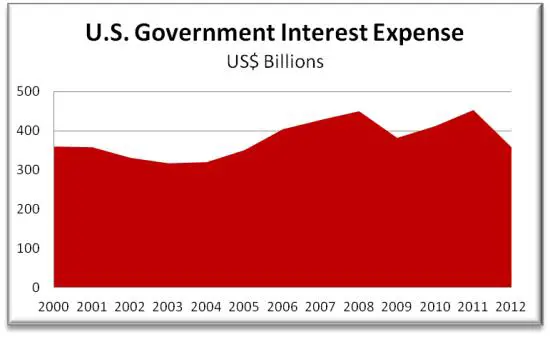

But the opposite is true for governments, for whom borrowing used to lead to higher interest expense, which in turn widened budget deficits. That’s no longer the case. In recent years, rolling over existing paper as rates have fallen has actually lowered the interest expense of investment-grade countries. Consider the following two charts. The first shows US government debt nearly tripling since 2000. The second shows how much its interest expense has risen: Not at all.

After a decade of massive deficits and rising debt, Washington’s interest expense remains modest because each new bond issue (and each rollover of existing paper) has been at lower rates. If you’re getting a Ponzi-like vibe, you’re right. This game can only go on as long as interest rates keep falling.

So how does it end? Possibly like this: First, US interest rates stabilize – which has to happen pretty soon because the average interest rate on new borrowing, at around 2%, is about as close to zero as it’s possible to get when 20 and 30-year bonds are in the mix. So this year’s $1 trillion-plus deficit will begin to add noticeably to interest expense, as will subsequent-year borrowings.

At some point, the markets will notice the new trend and seek a higher interest rate on new government bonds to compensate for rising risk. This will require the next few trillion of maturing debt to be rolled over at higher rates, which will kick interest cost expansion into overdrive. And that’s the end of the game.

Or the Fed will be forced to buy up all the bonds the government issues at below-market rates, which will, one has to believe, accelerate the dollar’s loss of purchasing power, with the same result: it gets harder and more expensive to borrow.

Unless Japan Blows Up First

But it won’t come to this because Japan is almost certain to enter a death spiral first. The short version of the story is that Japan responded to bursting real estate and stock market bubbles in the 1990s by borrowing huge amounts of money financed with domestic savings at minuscule rates, and has now accumulated government debt that dwarfs that of the US as a percent of GDP. Its economy is stagnant and debt continues to accumulate, so its newly-elected (and almost comically desperate) leader has demanded that the Bank of Japan create enough new yen to get inflation up to 2%. But here’s the catch: Japan’s current average interest rate is far lower than 2%, and if inflation picks up, so will interest rates, especially now that the country has used up all its domestic savings and has to borrow from foreign sources. According to hedge fund manager Kyle Bass’ calculations, if Japan’s average rate rises to just the US average of 2%, its interest cost will exceed the government’s total tax revenue. Here again, game over, and potentially in the next year or two, says Bass. See here and here.

…Or Derivatives

The idea that the world’s first and third biggest economies might soon enter a post-Ponzi debt crisis is scary enough. But it get worse. Turns out that of the $638 trillion notional value of derivatives now outstanding, $434 trillion, or 77%, are linked to interest rates. Let rates start rising, and tens of trillions of dollars of hedges will be activated, forcing the handful of big banks that are on the hook to…never mind. There’s no need to explain that the banks can’t meet those obligations so taxpayers, as in 2009 with credit default swaps, will be on the hook for another multi-trillion dollar bailout. Which will cause deficits and interest expense to go up. There really is no way out.

The only upside is that savers might finally start earning a decent return on their savings.

Visit John’s Dollar Collapse blog here >