The Elimination of Risk

Courtesy of Michael Batnick

Courtesy of Michael Batnick

Earlier this week I moderated a session at Inside ETFs called “How to capture outperformance and manage risk.”

Before tackling the challenges of outperformance, I wanted to ask everybody how they think about the amorphous concept of risk. The responses ran the gamut from “the chance of permanent loss of capital” to “the chance of running out of money” and everything in between. Risk is a gargantuan force that can’t be wrestled into one sentence or even a singular idea, but if you’ll allow me to channel my inner Charlie Munger via Tren Griffin for a moment- I think risk is best thought of through the prism of inversion; Risk is the opposite of risk-free. Risk-free however is a bit or a misnomer because risk rules everything around us.

Corey Hoffstein often talks about risk and the two ways it manifests in a portfolio-you can fail quickly and you can fail slowly.

The risk of failing slowly occurs, paradoxically, when an investor does everything they can to insulate themselves from it. What they fail to realize is that absent a high savings rate and a very high income, the avoidance of risk only delays the inevitable fact that risk is ever present. It is these investors who will fail slowly by allocating too much into assets like cash and bonds. The stock market provides different risk characteristics and is a more fertile breeding ground for failure in the sense that it gives investors the ability to fail quickly and slowly.

In order to put some meat on this discussion, let’s go to the numbers. Take the risk averse investor who saved 15% of their salary for 40 years starting at age 25. Each year their salary grew with the pace of inflation, with the savings going into one-month treasury bills. At age 66, they turn on the 4% rule- withdrawing 4% of the final amount saved and increasing that each year with the pace of inflation. Their money remains invested in one-month treasury bills (all numbers are net of inflation).

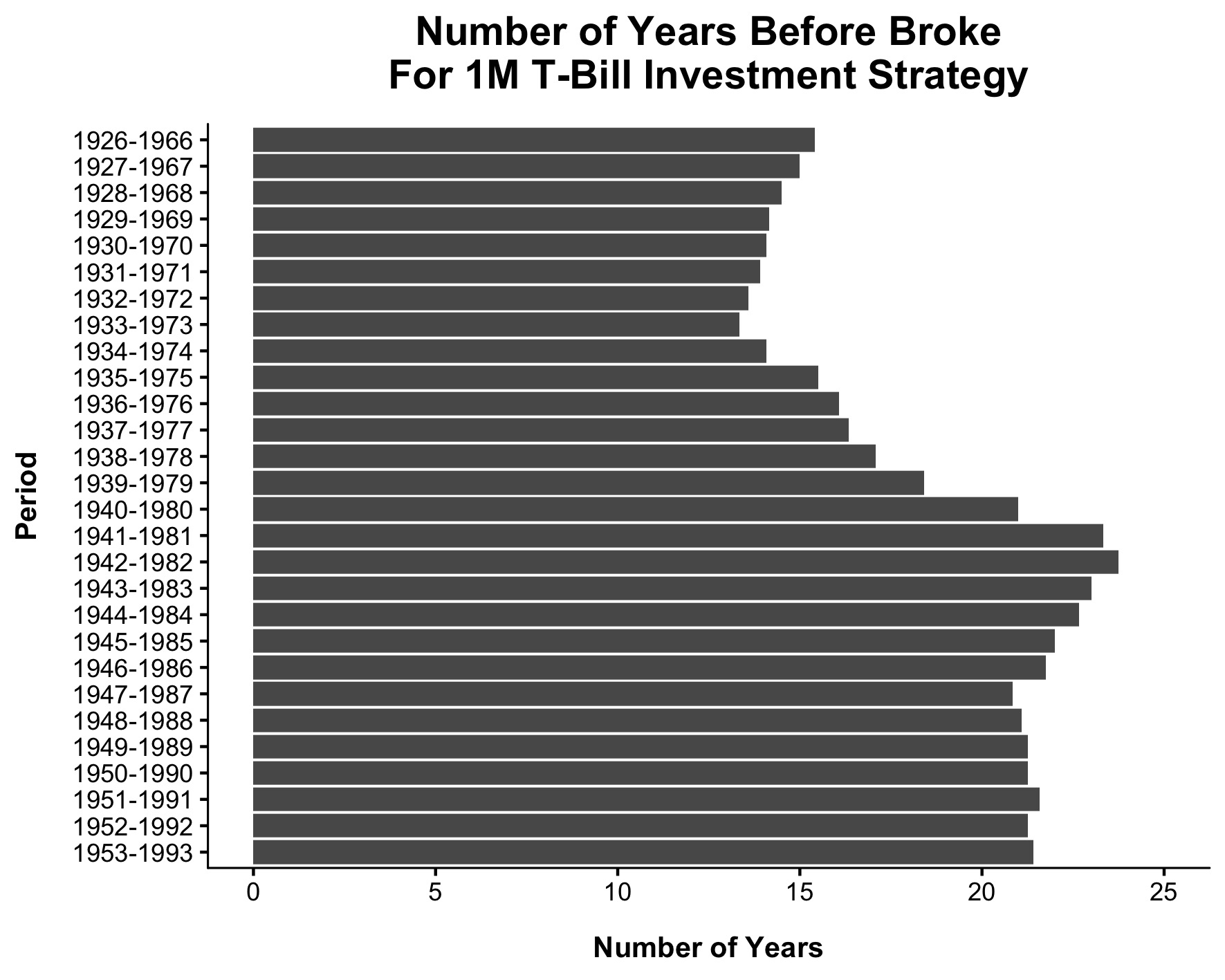

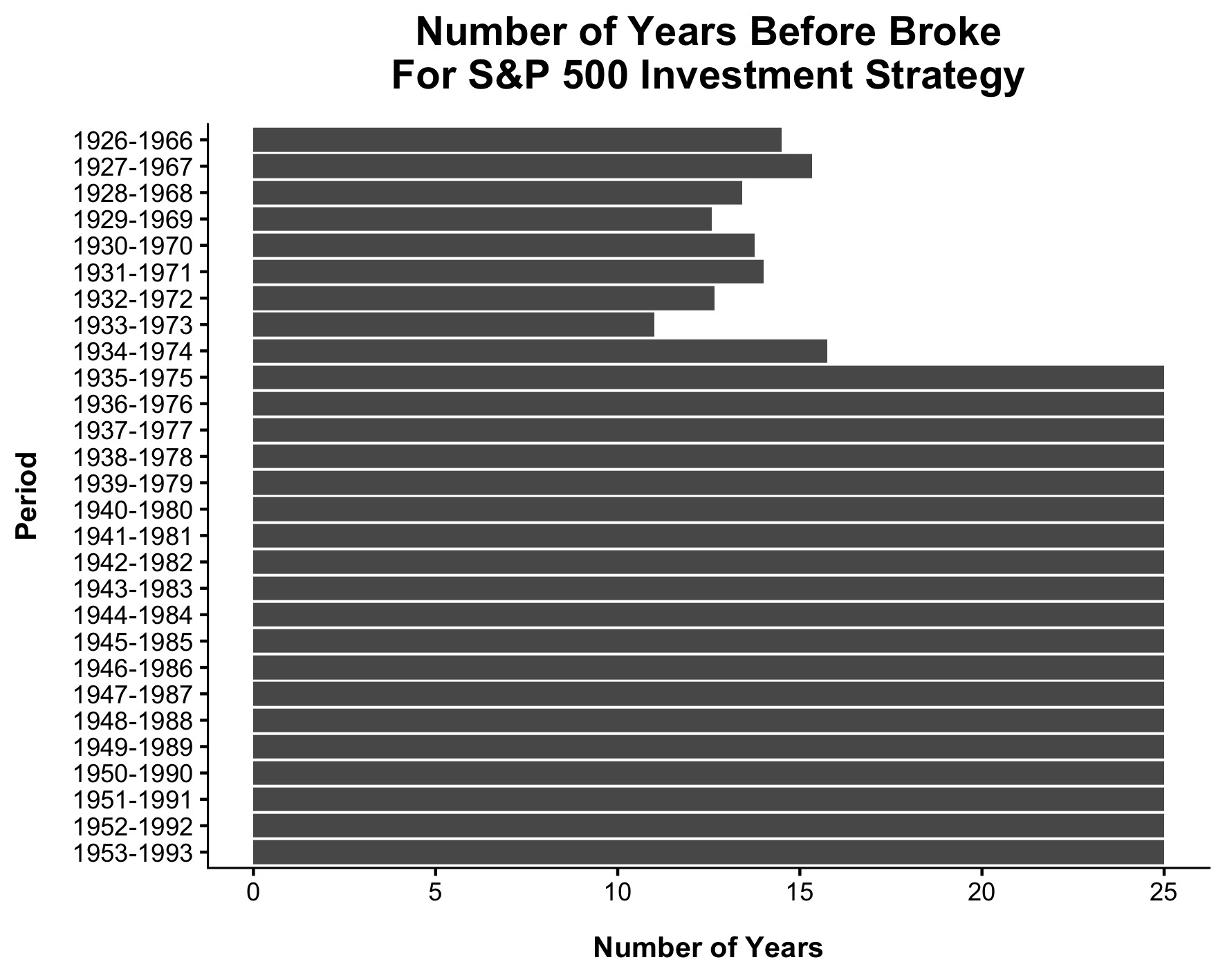

Starting in 1926, saving for 40 years, and then drawing down for 25 years only gives us 28 scenarios to measure. However, I think this is a fair representation of what sort of trouble the risk averse investor will run into. The chart below shows that the hypothetical risk averse investor would have run out of money in each of the 28 scenarios. The first column shows the investor who saved 15% of their salary every year from 1926-1966, and then used the 4% rule. On average, the first month spending would be 13% of your final monthly income. This is not enough to sustain oneself in retirement as this pile of money would run out on average after 15 years.

These numbers were made possible by the great Nick Maggiulli

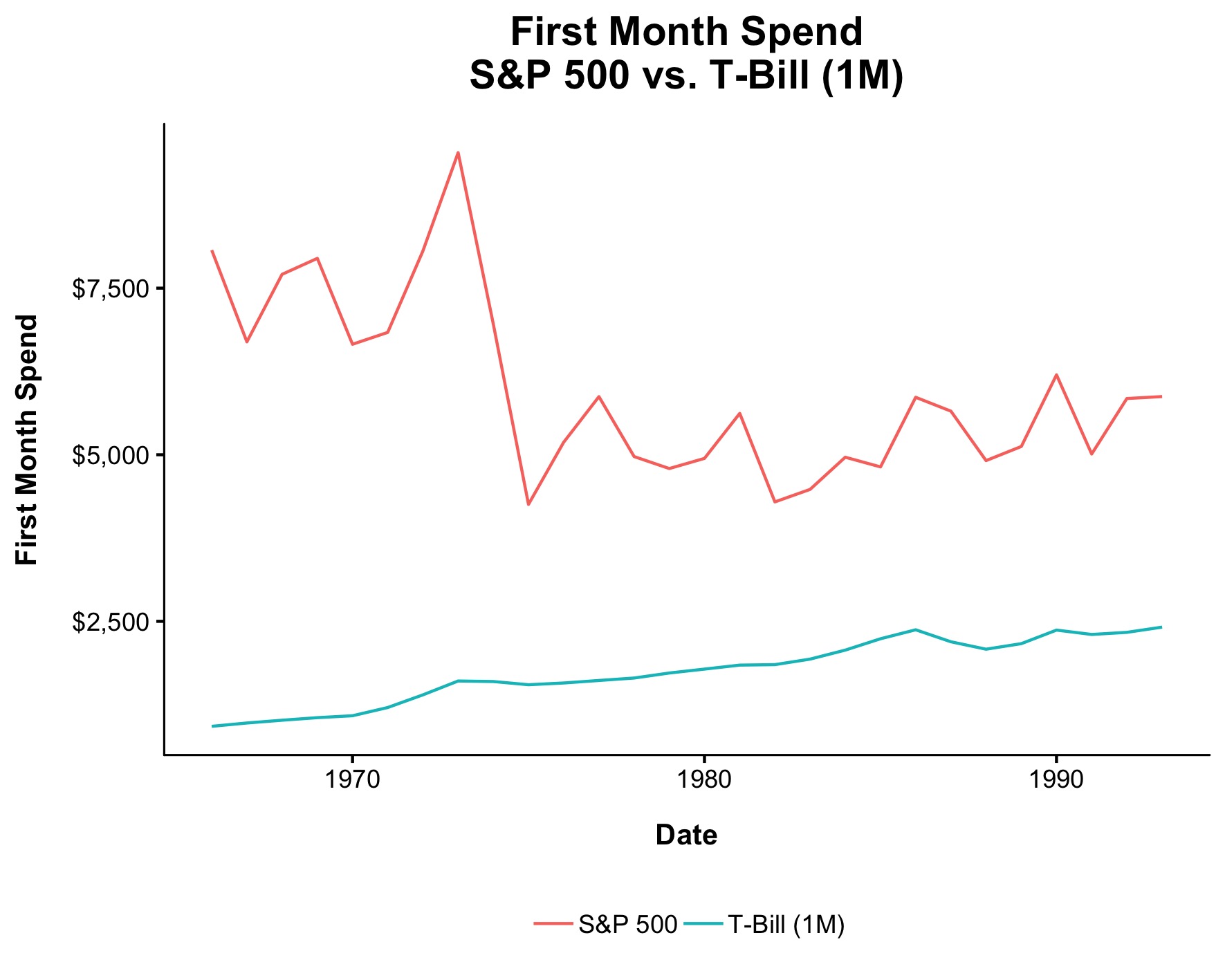

Not only does the risk averse investor run out of money, but this says nothing about the life they’d be able to live in retirement. The chart below shows how much an investor could have spent in their first month of retirement (after saving 15% for 40 years, and then turning on the 4% rule). The average amount withdrawn in the first month for t-bills is $1,750, or 13% of the average final monthly income. Had the investor gone the opposite direction and invested all of their money in the stock market, the average spending in the first month would be $6,000, or 52% of average final monthly income. As you can see in the chart below, stocks reward investors for the risk they took, and allowed for an average withdrawal in the first month that was four times larger than bonds.

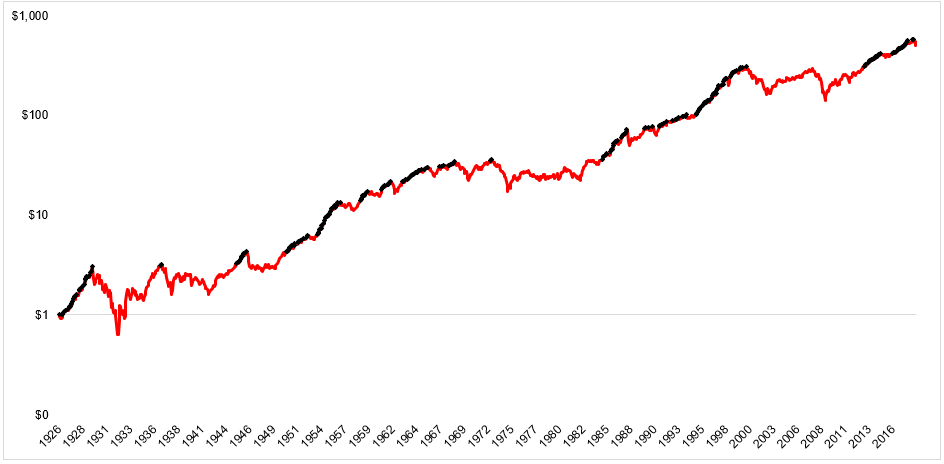

The stock market usually pays investors who bear risk, but it doesn’t always. The idea that you can see your wealth cut in half, stay the course, and still not be compensated is an uncomfortable reality that investors should come to grips with. You can eat your vegetables and still die prematurely. Even in the United States, one of the best places to invest over the last hundred years, there have been markets that were rife with risk and absent reward. The chart below shows S&P 500 adjusted for dividends and inflation. The all-time highs are in black, everything else is in red.

Had your retirement started in the throes of the 1973 red for example, you would have run out of money after only 12 years. Had your retirement started any year later than 1974, you were in the clear.

This whole exercise is hypothetical, of course. It assumes that index funds were around before they actually were, that there were no transaction costs, no taxes, and perfect behavior.

The point of this is not to convince you to forego the long-term risk in bonds for the short-term risk in stocks. As I already said, both are risky in their own ways. But rather, I hope this crystallizes one of the most critical concepts in investing. Risk cannot be eliminated. It can be measured and to some extent it can be managed, but it can never be eradicated. If the possibility of failure didn’t exist, there would be no risk. And if there were no, there would be no reward. Anyone who tells you differently is ignorant or deliberately lying.

The investor’s job is to figure out what risk means to them, how much they can stomach, and if necessary make changes along the way until their true ability to tolerate it is properly calibrated.