The Mother of All Pivots

Courtesy of Scott Galloway, No Mercy/No Malice, @profgalloway

-

Listen to This Newsletter

Audio Recording by George Hahn

The name of the podcast I co-host with Kara Swisher is “Pivot.” I don’t like the name, but I’ve had my hands on the wheel for so long at my own companies, I’m down with sitting in the backseat and occasionally asking, “Are we there yet?” Besides, Kara does most of the work and has a better feel for pods than me. But that’s not what this post is about.

A “pivot” is a strategic change in business model, direction, or target market. Think Netflix’s shift from DVDs to streaming, Adobe’s move to subscription, or Amazon’s launch of AWS. Sounds easy, but real transitions require a staggering investment and a leap of faith that make shareholders queasy. And, most of the time, they don’t work. Meta’s stock doubling in the last six months is a function of the market’s belief that The Zuck is waking up from his Big Gulp, Venti Grande Ayahuasca hallucination re a $20 billion-per-year investment in the metaverse. Meta’s earnings this week revealed Reality Labs (its opium den posing as a business unit) saw revenue decline to $350 million while losing $4 billion in the last 3 months. This means the birth control known as Oculus is pacing to lose the combined profits of Honda, BMW, and General Motors in ’23.

These bets are dwarfed by the greatest redirect in economic history: The Gulf States’ attempt to pivot from oil-based economies to something more sustainable.

Party’s Over

For the past century, the Gulf States have run on oil — and still do. State-owned oil giant Saudi Aramco is now more valuable than the next 10 largest energy companies combined, and last year it booked $161 billion in profits — likely the largest net income figure ever recorded.

Only, there’s a catch. The well is running dry. Regardless of the cadence of the move to renewables, the battery running the Gulf EV goes dead some time this century. Data re the oil remaining under the sand are closely guarded state secrets for the Gulf nations. But Bahrain is expected to run out within the decade, Oman in two decades, and the Kingdom by the end of the century, possibly sooner.

The plan to redirect this wealth into something else is unprecedented: building a next-generation civilization from scratch. Scratch, plus a few trillion dollars.

Its Own Moon

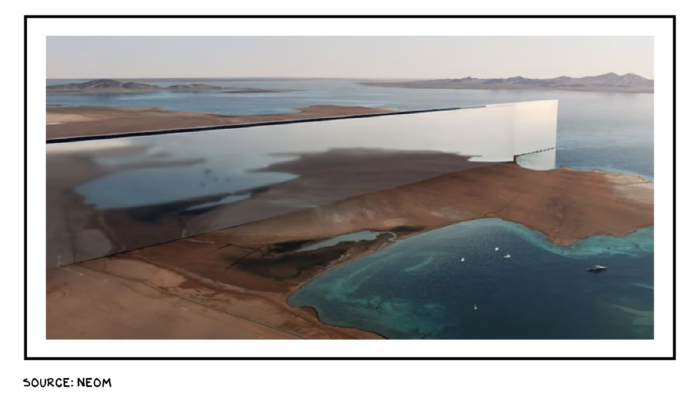

The scale and boldness of this bet is peerless. Let’s start with a 105-mile-long glass-domed mega-city in the desert to house 9 million people with no cars, staffed by robots, and powered entirely by wind and solar. Oh, and it will have a ski resort. And its own moon.

This sci-fi mega-city is the centerpiece of Saudi Arabia’s Neom project, budgeted at $500 billion. Keep in mind, that’s the budget — and 9 out of 10 mega-projects go over budget. Saudi Arabia is also building the Diriyah Gate, a $20 billion property development that will add 20,000 homes to the historic district of Diriyah, and the Red Sea Project, which will build 1,000 homes and 50 hotels across 22 small islands. Meanwhile, Qatar is building its own “city of the future” fit with a 90,000-capacity sports stadium, a dedicated entertainment district (“Entertainment City”), and the country’s first six-star hotel. No ski resort, though.

Bait

The secret sauce in the Gulf State pivot isn’t the oil money itself, however. That’s the bait. The prize is other people’s money. Specifically, rich people’s money. The plan, distilled, is to become the global headquarters for the mega-wealthy. This strategy increasingly makes sense as wealthy people continue to weaponize even democratic governments whose policies crowd more of the spoils into the top .01%.

The best way to attract the rich is to give them what they want. Which in 2023 means three things: luxury hospitality, world-class entertainment, and low taxes. The Gulf has gone all-in on all three.

The Saudis have launched their own ultra-luxury hotel brand, the Boutique Group, and Qatar owns The Plaza Hotel in New York and The Savoy in London. (Pro-tip: These weren’t property or even hotel acquisitions but brand acquisitions.) The United Arab Emirates built the iconic Burj Al Arab and has its own luxury hospitality university. Ever fly Emirates, Etihad, or Qatar airlines? (Think in-air shower spa.)

Middle Eastern interests now own many of the world’s most iconic football clubs, including Manchester City, Paris Saint-Germain, and Newcastle United. Qatar spent $220 billion on the FIFA World Cup (more than the last seven World Cups combined), and many critics accused it of “sportswashing” — using love of sports to distract from its human-rights record. And sportswash it did: The Qatar World Cup had the highest-ever attendance in the tournament’s history, as well as one-fifth of the world population watching the final. I attended, and the investment, sample size of four, had its intended effect.

Saudi Arabia operates a Formula One Grand Prix site and the LIV Golf tournament, which nabbed several high-profile golfers and offered Tiger Woods $800 million to join (he declined). They’ve also pledged billions of dollars toward finding the “Arab Damien Hirst.” The Emiratis are building a $27 billion culture center on Saadiyat Island featuring the Frank Gehry-designed Guggenheim Abu Dhabi and the Jean Nouvel-designed Louvre Abu Dhabi, and Qatar commissioned Nouvel to design its $434 million National Museum of Qatar.

Marketing for these mega-projects is multipronged and not always subtle. Last year, my 12-year-old emerged from a YouTube K-hole and said, “Dad, did you know you can stay in a hotel that’s in the biggest building in the world?” That didn’t sound that great to me, but it did to him — and sure enough, we stayed at the Armani Hotel in the Burj Khalifa, the tallest building in the world, on our World Cup tour of the region. We have been to the Gulf three times in the last six months.

The Middle East is a museum of superlative landmarks, the branding brash and effective. Dubai has the tallest Ferris wheel, Jeddah’s F1 track is the fastest, and after the race, your family of four can drop $2,200 on a lovely but unremarkable dinner at the world’s most expensive Greek restaurant (Nammos). My dad didn’t speak to me for two days when I ordered a $3.25 malt shake at the Lahaina Baskin & Robbins in 1977.

The final puzzle piece: taxes. Or lack thereof. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, and Qatar have some of the world’s lowest tax rates. Similar to what London did 30 years ago, Dubai is committed to deregulating its financial sector. The city is drawing in new firms with reduced licensing fees and capital requirements for hedge funds that domicile there. And the UAE is attracting wealthy Russians with its bold position on the war in Ukraine: neutral.

Hard Power

Speaking of … the only thing that bests soft power is hard power — the ability to deliver violence abroad known as military spending. The Kingdom’s military expenditures reached $75 billion last year, the fifth highest in the world, and more than any nation in Europe except Russia. Big military spenders either invade nations (Iraq, Ukraine) or have the world on tenterhooks guessing where they will invade (Taiwan). To believe Saudi won’t flex its power is naive.

Back to the big shiny stuff they’re building. …

The Elephant in the Private Zoo

What’s not to like about this plan? The sheer audacity is notable. But the Gulf nations have experience with massive projects — you don’t pump 13 million barrels a day without knowing how to build — and a deep appreciation for outside experts. They are recruiting, from the four corners of the Earth, people and small firms that range from banks to ad agencies, paying them multiples of what they can make at home, and asking them to build the future. It’s not without huge issues. Some of those Western experts have quit; according to the Wall Street Journal, Neom CEO Nadhmi al-Nasr is on tape telling underlings in a meeting, “I drive everybody like a slave. When they drop down dead, I celebrate.”

Western consultants being overworked is not what gives us pause about this vision. Al-Nasr’s reference to workers dropping dead was probably meant metaphorically, only it’s not just strong language — we don’t know how many migrant workers died building the World Cup venues in Qatar, but the Qataris have admitted to over 400. And there’s no escaping that the Gulf nations hold a different view of personal liberty than the West. On some levels, this is easy to address, and these envisioned cities will enjoy some additional liberties. Alcohol will be widely available, there won’t be dress codes, and there are signals of an increasing tolerance for people’s religious and sexual preferences that isn’t enjoyed elsewhere in most Gulf nations. We’ll see. The track record isn’t great.

The concerns become dystopian fast. Neom will be run by an operating system called Neos, and every resident will have a unique ID number, with 24/7 tracking. No need to carry keys, since Neos will know which doors you are supposed to be able to open. No need to carry money; Neos can put it on your tab. No need for Mohammed bin Salman’s security apparatus to hack your phone to listen in on all your conversations, either.

If You Build It, They Will Come

Will rich people want to live in a future built by the same people who murdered a journalist? The sober answer is yes. People care about human rights. However, most people, most of the time, care more about their prosperity even if it comes at the expense of others. Think Big Tech.

The early indications are that using money to attract money … works. The Gulf has become a premier destination for fundraising efforts. In just the past few weeks, venture firms including Andreessen Horowitz, Tiger Global, and IVP have held high-profile events in the Gulf. “The Four Seasons in Riyadh,” according to one prominent venture partner, “is basically Palo Alto.” An executive in the UAE’s investment company said, “We came to San Francisco looking for them in 2017. Now everyone is coming to us.”

Some are coming to stay. Ray Dalio is setting up a branch of his family office in Dubai, and big-name hedge funds, including Millennium, ExodusPoint, and BlueCrest, all have offices in the Gulf already. The UAE registered a net inflow of 4,000 millionaires in 2022, and in Dubai, $57 billion in real estate changed hands, up 80% from 2021, including 86,000 residential properties and 219 homes worth over $10 million.

There is merit to the suggestion that a decent strategy for success is to find the largest pile of money and stand as close to it as possible. The largest pile can now be seen from all continents, and millions will migrate. Does this represent a subjugation of Western values to money or the realization that capitalism’s self-interest is the premier force in a modern world? The answer is yes. Strategy is leveraging your strengths to do something that is really hard, ideally impossible for others. The Kingdom’s strengths are unprecedented capital and a willingness to play the long game. So, how does this impact you? Nothing draws human capital like capital. If you live in the West or South Asia, one of your kids may well end up in the Gulf. Is this good or bad? I don’t know. It just … is. We’re witnessing the mother of all pivots.

Life is so rich,

![]()

P. S. This week on the Prof G Pod I talk with Bill McKibbon about media shakeups and the state of climate change. Listen here.

P.P.S. I’m teaching Business Strategy and Brand Strategy back-to-back in May. If you haven’t signed up yet, you can check out lesson one for free.