Fifty-one percent of Americans aged 18 to 24 believe the Hamas attacks of October 7 “can be justified by the grievances of the Palestinians.” That’s not how most Americans feel, and the disparity in sentiment is correlated with age.

This is not unique to the Hamas attack. The older you are, the more likely you are to be pro-Israel: In March 2022, 69% of Americans over 65 had a favorable view of Israel, while just 41% of those under 29 did. Worries about increasing antisemitism in the U.S. are similarly correlated: 85% of seniors say it’s growing; 52% of Gen Zers say it’s not.

Young people are resistant to the views of their elders. And that’s a good thing. As kids enter adolescence, they develop a healthy gag reflex triggered by anything associated with their parents. This helps them develop their own opinions and beliefs about the world, and it’s also good for the parents, because by the time kids are 18, they can be such assholes that everyone’s ready for them to leave the house.

But that doesn’t explain students at my employer (NYU) holding up protest signs reading “keep the world clean” with images of the Star of David in trash cans. I’d like to think this is a fringe view, but when 51% of their cohort believe the murder of 1,200 people is justified, something more serious is happening.

Young people’s attitudes about Israel have been hardening for some time: Months before October 7, a majority of Americans under 43 were more sympathetic to the Palestinians than the Israelis. Yet during that time, U.S. policy has remained staunchly pro-Israel, and American media generally favorable toward Israeli interests. That gap is widening into a gulf, between establishment views and those of young people. All of which made me think of … Dresden.

125,000

In 1945 the U.S. and British air forces rained 4,000 tons of high-explosive bombs on the German city of Dresden for 48 hours straight. The attack was militarily advantageous. It impeded German troop movement, destroyed a key city center, inflicted heavy German casualties, and, as the officers of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey put it, “left the German people with a solid lesson in the disadvantages of war.” It also destroyed acres of historical and culturally priceless art and architecture and killed 25,000 civilians.

The Allies considered it such a success that a month later the U.S. repeated the tactic at an even greater scale on the other side of the globe, destroying 16 square miles of central Tokyo and killing 100,000 civilians — making March 9, 1945, the deadliest night in human history. Four months after that, Truman ordered the atomic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Contemporary assessments and public opinion in the U.S. focused on the military advantage gained from these attacks, and little mention was made of the horrific human toll. It had no measured impact on U.S. support for the war or those prosecuting it.

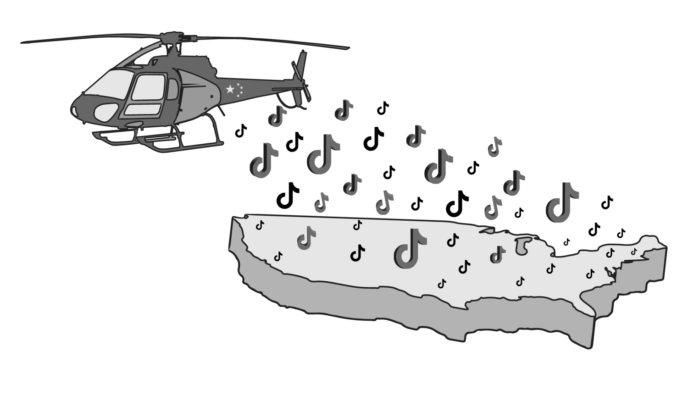

What would have happened if the people of Dresden had had TikTok? The same TikTok that is serving me dozens of videos from Gaza, epitomized by a couple taking cover with their innocent child from Israeli bombs. Around them only rubble. Heartbreaking. Heartbreaking enough to make you hate those behind the bombs, whatever their flag or justification.

Three Photos

For most of modern history, governments and elites have had outsized influence on the narrative, especially around foreign affairs. Outright, 1984-style control is unnecessary, when words, sounds, and images are only accessible through controlled channels. Corporate ownership of media, access journalism, and bias go a long way in choosing what stories to cover and how to frame them.

The exceptions prove the rule. When contrary evidence breaks into public awareness, the impact can be profound. Just three photos shifted U.S. public opinion against the Vietnam war more than thousands of dead American soldiers or lost battles: the 1968 image of a South Vietnamese General shooting a prisoner in the head, the 1970 picture of Mary Ann Vecchio kneeling over the body of a Kent State classmate, and the 1972 image of a naked girl fleeing napalm. If you are over 50, you likely can recall these images just by closing your eyes. If you are over 70, you don’t need to close your eyes. Regimes that lose control of the narrative lose power soon after. The shift in American opinion about Vietnam brought down LBJ. The Gulag Archipelago fatally undermined the Soviet Union’s historical and moral narrative. Ayatollah Khomeini’s taped sermons brought down the U.S.-backed Shah of Iran.

All governments seek to shape the narrative. Vietnam was called the “living room war” because media, especially television, brought it home in ways that newsreels never did during World War II or the Korean War. The lesson the U.S. military took from the experience was a simple one: It had to regain control of the narrative. It implemented a system of “embedding” journalists within military units, which, of course, meant what the journalists saw and how it was presented to them fell largely under government control. Embedding put the genie back in the bottle for a generation. But social media, especially the short-form video format popularized by TikTok, has shattered the bottle.

The Mobile Screen War

Young Americans spend at least 10% of their waking hours on TikTok, and 76% of 18- to 24-year-old Americans are TikTok users, compared to 7% of Americans 65 and older. That’s time they are not spending watching CNN or reading the Wall Street Journal. And on TikTok, the scale and reach of pro-Palestine content dramatically outweighs pro-Israel content. As of this week, videos tagged #StandWithPalestine have received more than 10 times the views of videos tagged #StandWithIsrael — 324 million vs. 3.4 billion. One TikTok user reported that his stream turned rabidly anti-Israel once he started engaging with such posts, and Jewish creators on the platform are reporting escalating harassment.

Cause / Effect

This is cause and effect. Young Americans (see above) are already drifting away from the attitudes of their parents’ generation (my generation) toward the conflict. Young Americans are more diverse than older Americans, and presumably more sympathetic to non-white groups such as Palestinians. And if mostly what you know about Israel-Palestine is Gaza post-2006 and bulldozed houses in the West Bank, your views are likely going to be different from those of someone whose frame of reference includes the Yom Kippur War and Munich. Young people are more prone to make pro-Palestinian content, more prone to consume it, and the wheel turns.

Accuracy Is Incidental

Access to more viewpoints and more sources of information is a good thing on balance. Despots should not be allowed to disappear their people any more than democracies should be able to firebomb someone else’s, and the unflinching testimony of a livestream can help stop them. But an unbounded information landscape is not an unalloyed good. Because social media does not favor accuracy or balance or diversity. It favors clicks. The more engaging and enraging the content, the more clicks it receives. Is the image I get of Gaza on TikTok more accurate or true than what I see on CNN? In some cases, yes. But on social media, accuracy is incidental. This presents, I believe, two profound risks.

Where We Spend Our Time

Sam Harris said you become where you spend your time. We were discussing Twitter on my podcast — I was addicted to it at the time, and I had noticed I’d become more curt, venal, and reactionary. Also, I was having thoughts in 140 characters (no joke). He pointed out that humans are more influenced by our environments than we’d like to think. If I spend 5% of my waking hours getting angry on Twitter, I become a 5% angrier individual. Same is true if I spend more time with my kids expressing and receiving love. We become where we spend our time. (Side note: I am no longer using Twitter.) (Another side note: still angry and curt.)

Just as my addiction to Twitter made me more like what I consumed there — sputtering angry hot takes — spending time on the TikTok of #standwith___ has a predictable effect. The conflict, generations old and woven into the fabric of global politics, is reduced to suffering, anger, and violence. There is a good side and a bad side. Instinctive tribalism kicks in, and young people walk through Washington Square Park with images of the Star of David in the trash, and a 6-year-old Muslim boy is stabbed by his landlord. Social media algorithms identify our politics and then shepherd us into a hermetically sealed bubble, framing our worldview through a window of rage and extremism.

CCP(roblem)

We know the first risk is real, and it’s playing out — you can see it on your phone and in the street. Our discourse is more coarse, our focus increasingly on what divides us. The second risk is more insidious, visible only in outline. But those outlines are coming into sharp relief. There is a nonzero probability that TikTok is being manipulated and leveraged by the CCP to sow division in America. That probability is high. It’s what we would do and have done. In the Cold War, both the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in a variety of covert actions aimed at fomenting internal strife. Radio Free Europe, a CIA-backed initiative, broadcast pro-democracy messaging into the Eastern Bloc to encourage dissent. During World War II, Nazi Germany dropped leaflets over American troops that highlighted racial injustices in the U.S., hoping to demoralize troops and incite racial tension. Every nation has done, or is doing, this … actively. The U.S. itself continues to pursue such tactics to this day. The U.S. Army’s 4th Psychological Operations Group describes itself as follows:

The CCP has control over the most powerful, yet elegant, weapon in the history of propaganda, and the default position is they (i.e., the CCP) are not using it? I have stated this view before. China cannot beat us kinetically or economically, but it can beat us by tearing us apart from the inside. TikTok, in my view, has the potential effect of several carrier strike forces. A 21st century Trojan Horse that also generates $100 billion in annual revenue. I was at the White House this week for an AI Summit. Government officials are not allowed to be on TikTok for security reasons. This comes at a cost, as I believe they’d be more alarmed at the skew of information.

It’s a common misconception that propaganda is like advertising: a barrage of messaging favoring one side or attacking another. Uncle Sam telling you to buy war bonds or black-and-white movies of Aryan youth saluting the swastika. That’s not how China would use (is using) TikTok. The more elegant strategy is to atomize the enemy (us). Find small differences of opinion and broaden them. Carve off slices of support for a long-time ally, one demographic group at a time. The Nazi propagandist Goebbels wrote that the purpose of propaganda is to generate “volcanic passions, outbreaks of rage, to set masses of people on the march, to organize hatred and despair with ice-cold calculation.”

Xi Jinping has described the Internet as “the main battlefield in the battle for public opinion,” and in 2013 he said, “online public opinion work should be taken as the top priority of propaganda and ideological work. Many people, especially young people, do not read mainstream media and get most of their information from the Internet. We must face up to this fact, increase investment, and seize the initiative on this battlefield of public opinion as soon as possible. [We must] become experts in using new means and methods of modern media.” ByteDance employees have confirmed the CCP has backdoor access to American TikTok user data, which it has used several times. In addition, the CCP has refused to let TikTok’s parent company ByteDance go public for national security reasons. FBI officials have themselves stated TikTok could be used as an “aggressive weapon” against the U.S. and China’s enemies at large. In sum, the CCP’s manipulation of TikTok is hiding in plain sight.

Oppenheimer Moment

The CCP’s Oppenheimer moment was the fusion of TikTok and October 7. Or maybe I’m being paranoid and am out of touch with a generation reacting to an Israel that has veered rightward. Maybe an increasingly non-white population has an easier time recognizing oppression. Or maybe we live in a social media era in which views are ushered to their most extreme on their own without interference from state actors.

Maybe.

Life is so rich,

![]()

P.S. This week on Prof G Markets we discussed Meta’s monster quarter and the U.S. deficit. Listen here. (Or watch.)

P.P.S. Section’s AI Mini-MBA is now open to all time zones. In four weeks, you’ll learn how to build an AI strategy for your business and understand the AI landscape. Register here and start in January.