How the ‘Mexican miracle’ kickstarted the modern US–Mexico drugs trade

Conflicts between rival drug cartels and government forces in Mexico have claimed hundreds of thousands of lives, leading to violent social breakdown across the country.

The flow of cheap and deadly fentanyl over the border into the US has also fuelled an opioid epidemic that has killed over 1 million Americans since 2000. The epidemic has prompted threats from the Republican presidential candidate, Donald Trump, to send troops into Mexico to battle the cartels if he wins the 2024 election.

But despite all this horror, the story of the Mexico–US drug trade is less a tale of cops and kingpins than it is a fable about the unintended consequences of government policies on both sides of the border.

My recent research shows that the emergence and expansion of the US–Mexican drug trade was inseparable from state-sponsored processes of social, political and economic modernisation. It is a dark side to the so-called “Mexican miracle” that transformed the country’s economy between the 1940s and 1970s.

Stimulated by the Mexican and US governments’ promotion of infrastructure improvements and mass migration, the drug trade fuelled further lawful economic development throughout the country. This makes it part of the very foundation of Mexico as we know it today.

Cops, cartels and cash crops

The state of Durango in northern Mexico provides a perfect example. Here, the violence of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920), combined with the economic shock of the Great Depression (1929), led to the closure of the gold, silver and lead mines that had once been the lifeblood of the economy.

Many of Durango’s battled-scarred and poverty-stricken former miners adapted to the national and global turbulence by turning to opium poppies, a profitable (and since 1920, illegal) cash crop. Sap from opium poppies provides the raw material for drugs like morphine and heroin.

Opium cultivation in Durango took off in the 1940s. The second world war cut off US drug dealers from their traditional suppliers in Europe and Asia, stimulating demand for heroin made in Mexico. In response, US officials like Harry J. Anslinger promoted a “crusade” against the drug trade on both sides of the border.

This involved sponsoring and supervising militarised campaigns in places like Durango. In 1944, a joint US–Mexican expedition uncovered the largest opium plantation ever discovered in Mexico: the size of 325 football pitches. It would have yielded four and a half tonnes of opium per harvest – enough to produce an amount of pure heroin worth more than US$27 million (£21.3 million) on today’s market.

However, local political bosses, police chiefs and military commanders protected, taxed and even directly invested in Durango’s opium trade, sabotaging the campaigns being waged against it. In so doing, they avoided conflict with their constituents and took a cut of the illicit profits for themselves. These profits boosted the local economy and eased its integration into Mexico’s mainstream.

Cold war Mexico

As the second world war gave way to the cold war, Latin American countries (often with US financial assistance) promoted urbanisation, industrialisation, infrastructural expansion, population growth and transnational economic integration. They did so to counter the perceived threat of homegrown communist subversion.

Between 1950 and 1970, Mexico’s one-party state invested massively in public services and industrial and agricultural development. This doubled the size of the economy and transformed a predominantly rural society into a modern, consumer-capitalist, majority-urban one.

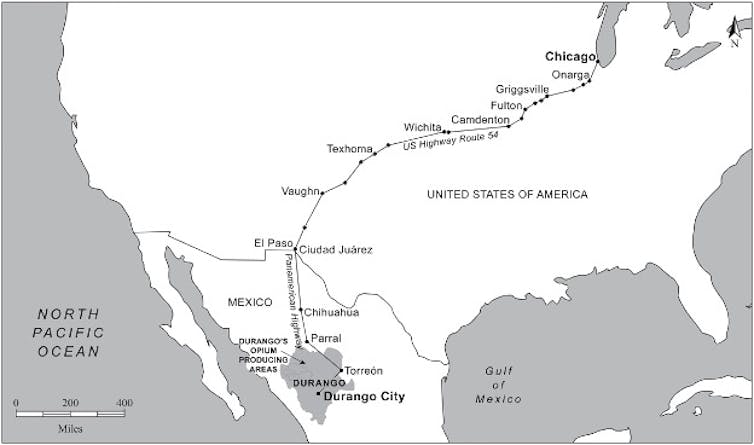

This Mexican miracle also transformed the drug trade. New roads were built to promote capitalist development, integrate the Mexican and US economies, and allow for easier military movements as part of a policy of “hemispheric defence” against the Soviets. But they helped connect the poppy fields of Durango to the rest of northern Mexico and the US border too.

These roads also facilitated the departure of thousands of people from rural Durango to the US as part of the “Bracero” temporary worker programme. This programme sought to resolve American labour shortages while also teaching Mexican workers new skills and techniques with which to “develop and modernise rural Mexico” when they got home.

However, many of these migrant workers never returned. Many Durango-born braceros ended up in Chicago, where they formed the core of a tight-knit community. By the mid-1960s, as heroin use surged in big cities across the US, members of this diaspora began to secure the drug from contacts back in Durango for distribution in their new home city.

Heroin from Durango-grown opium poppies was then hidden in cars and driven by mules up the Pan-American Highway to Chicago – a 50-hour journey along a route by now familiar to two generations of migrants.

The ‘heroin highway’

This new trafficking route soon became known as the “heroin highway”. It consolidated Durango’s importance as a Mexican drug-production centre and transformed Chicago into the biggest heroin-trafficking hub on the continent.

But it also contributed to the further development of Mexico itself. The cash that trafficking organisations earned wholesaling heroin in the US was reinvested locally in everything from cattle ranches to construction companies and even an airline.

In this sense, the birth, expansion and consolidation of drug production and trafficking in Durango was not due to the failure of state-led development. Instead, these were completely intertwined with the economic growth, infrastructure development and mass migration that characterised the Mexican miracle.

The story of the modern US–Mexican drug trade is not just about brutal violence and lives cut tragically short. It is also about transnational capitalist victories, built on the sweat and toil of the kinds of people US and Mexican policymakers want everyone to be: from the peasants in the mountains of Durango chasing the Mexican miracle, to the illicit entrepreneurs in Chicago trying to live the American dream.![]()

Nathaniel Morris, Honourary Lecturer, Department of History, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.