The world's nuclear energy watchdogs: 4 questions answered

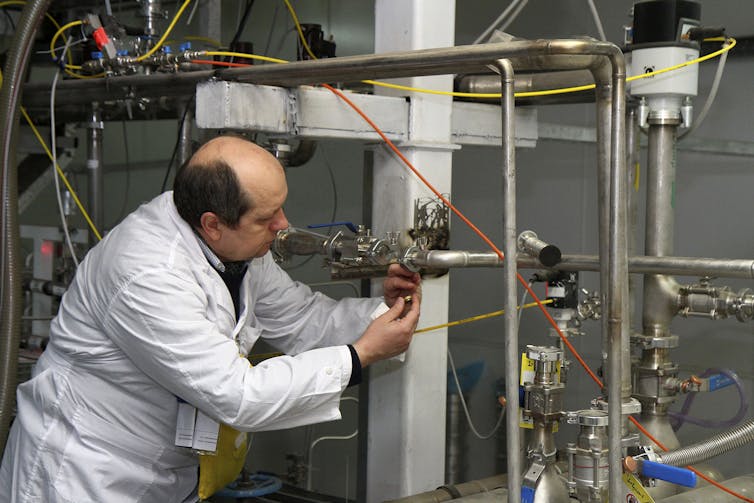

An International Atomic Energy Agency inspector at Iran’s Natanz facility, 2014. AP Photo/IRNA, Kazem Ghane

Courtesy of Scott L. Montgomery, University of Washington

North Korea has promised to get rid of its nuclear weapons, but how will the world know if it actually follows through?

There is only one international agency in the world that could verify their compliance, the International Atomic Energy Agency. However, North Korea canceled its membership to the organization in 1994. When the IAEA demanded to inspect certain facilities in North Korea, they backed out and eventually expelled all nuclear inspectors in 2009.

Since then, North Korea has remained outside the IAEA’s jurisdiction. While it isn’t clear whether the agency will be called upon if a deal on denuclearization is reached, IAEA Director General Yukiya Amano has said the agency is prepared to send a team of inspectors should a diplomatic agreement be reached.

So, with that possibility in mind, let’s look at how the agency operates and all the other nuclear energy challenges it faces beyond North Korea.

1. What is the International Atomic Energy Agency?

The IAEA was founded in 1957, inspired by U.S. President Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” speech promoting the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. From the beginning, its task has been to spread and monitor the application of nuclear technology for non-military uses and make sure that such technology is not diverted to build weapons.

Its creators had a mixture of pragmatic resignation and long-term hope about nuclear technology. They recognized that the Cold War meant that nuclear weapons would continue to exist. Yet the thinking was that their existence might be significantly curtailed if nations were drawn to other applications of the technology like medicine, agriculture, industry and power generation.

Headquartered in Vienna, Austria, the agency is a membership organization that reports annually to the United Nations, but is independent of it. Member nations must obey its rules and requirements in order to receive the knowledge and technology it provides.

Currently, 169 countries are members.

2. What are the agency’s main responsibilities?

The agency is best known for its work in two areas. The first is nuclear safety: protecting people and the environment from harmful radiation. The second is nuclear security, which focuses on preventing the spread of nuclear weapons, including threats of nuclear terrorism.

This watchdog role requires determining whether any member country might be developing nuclear weapons – specifically nations that have signed international treaties. For example, the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons is the world’s most important legally binding agreement for preventing the spread of nuclear weapons. At present, a total of 191 states have joined the treaty. Three nuclear weapons states – Israel, India and Pakistan – have not signed and North Korea withdrew from it in 2003.

The IAEA evaluates compliance with other treaties including those governing nuclear free zones and important safeguard agreements with as many as 181 nations.

In the past, some states like West Germany and Italy, and more recently Iran, have viewed the agency’s authority as unfairly restricting their sovereignty over their nuclear facilities. Yet support for the agency’s authority has grown strongly with time, due to its key role in difficult cases, like that of Iran itself.

3. How does the agency verify how nuclear material is being used?

Among the more than 2,500 people who staff the IAEA, only about 385 are inspectors. They come from 80 nations and mainly hold backgrounds in physics, chemistry and engineering.

Routine inspections involve verifying whether a member’s report about its nuclear facilities and material is accurate. Depending on the size of the facility, this might take a few hours for one or two people or two weeks for 10 inspectors. They do this in a number of ways, including the collecting of samples of nuclear material, measuring levels of radioactivity, checking plans and blueprints against actual construction, and interviewing officials, engineers and others involved in nuclear work.

Over time, the agency has had to make changes in its inspection processes. For example, before 1997, inspectors were limited to examining only facilities that member states had declared. After discovering that Iraq had lied about the true extent of its nuclear program, the IAEA board of governors approved a protocol to allow inspectors to access undeclared sites that might be involved in nuclear work.

Inspectors have also found themselves in the line of political fire. For example, between 2002 and 2003, the Bush administration wanted evidence that Iraqi President Saddam Hussein had an active nuclear weapons program. U.S. attempts to pressure the agency did not alter IAEA findings that such evidence could not be found.

Similarly, the agency has stood its ground in favor of the Iran nuclear deal and Iran’s compliance in the face of President Trump’s continued criticism of the agreement.

4. What are the main challenges facing the agency?

There are myriad challenges facing the IAEA.

Expanding demands on the agency have come from developing nations with growing economies such as Thailand and Chile that want to use nuclear science in medicine, agriculture and industry. Growth of nuclear power into new areas of the world is bringing concern about the development of weapons and terrorist groups acquiring nuclear material.

North Korea, whose weapons program may or may not be halted by talks with the U.S., has plutonium and uranium that could be sold without international approval or safeguards.

Then there is the Trump administration’s threat to abandon the Iran nuclear deal, a move that would dismiss years of effort by the IAEA to head off an arms race in the region. At the same time, any future need to verify that Iran is not building a weapon would almost certainly rely on IAEA inspectors. Similarly, it seems likely that a deal between the U.S. and North Korea would require the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea to rejoin the agency and have any denuclearization efforts confirmed by it as well.

Such realities only heighten the importance of the IAEA. No other organization exists to do its essential work. One of its most successful and farsighted efforts has been to work with nations individually in creating blueprints for safe nuclear science and nuclear power programs.

The most enduring difficulty facing the IAEA, however, lies with the U.S. and Russia. Despite reducing their nuclear arsenals hugely since the Cold War, both still possess around 7,000 weapons, immense numbers considering each one’s destructive power. Both nations, moreover, have recently and openly declared a new era of modernization and diversification for these arsenals.

In their very existence, these weapons are a rationale for other countries to want them. How else will they deter aggression from either nation? It remains a stark truth, a difficult one for the IAEA, that while it works to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons, the U.S. and Russia forge a path for weapons states in exactly the opposite direction.

Scott L. Montgomery, Lecturer, Jackson School of International Studies, University of Washington

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.