Reminder: Pharmboy is available to chat with Members, comments are found below each post.

Could this be the year for a Canadian Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences?

Courtesy of John Bergeron, McGill University

In 2013, Kyoto University’s Shinya Yamanaka was awarded one of the first Breakthrough Prizes in Life Sciences for his discovery of “induced” stem cells that enabled researchers to convert adult cells back into stem cells.

The Breakthrough Prize is not to be sneezed at. Founded in 2013, the prize “honours transformative advances toward understanding living systems and extending human life.” It’s also the most financially attractive award in science, valued at US$3 million. And the winner is able to use the money as they wish.

That same year, Hans Clevers from the Hubrecht Institute in Utrecht was separately awarded a Breakthrough Prize for his discovery of tissue stem cells and cancer.

It was actually three talented Canadian scientists, however — Charles Leblond, Ernest McCulloch and James Till — who first discovered stem cells.

Indeed, several talented Canadian researchers are deserving of this lucrative prize. Yet in the six years of its life so far, no Canadian has received it in the life sciences.

As the April 30 deadline for this year’s Breakthrough Prize nominations approaches, we have to ask why.

Who discovered stem cells?

Clevers readily acknowledges that his discovery in 2007 of the stem cell in the small intestine confirmed the prior seminal discovery of the same cell — by McGill University’s Leblond decades earlier.

Leblond may be the scientist who first discovered stem cells as based on his breakthrough paper on the “stem cell renewal theory.”

The breakthrough was first published in 1953 and considered by many to be as important a discovery as that published by Watson and Crick for the double helix the same year.

The link between stem cells and cancer is also a Canadian discovery. University of Toronto researcher John Dick discovered the cancer stem cell in 1994. Dick’s breakthrough was based on his use of a stem cell assay to study leukemia.

The stem cell assay he used was in turn based on a prior breakthrough by Till and McCulloch. They have been widely acknowledged for their groundbreaking 1963 discovery of the stem cell in the bone marrow responsible for the formation of red blood cells, platelets and white blood cells.

Elegant techniques

The pioneering breakthroughs of Leblond, Till and McCulloch are due to the elegance and craftsmanship of their experimentation.

In 1953, Leblond and his student Yves Clermont deduced the primordial cell they called a stem cell. This cell gave rise to over 45 different recognizable cells whose lineage they could precisely map during the process known as “spermatogenesis.”

They devised an elegant chemical staining technique to distinguish cells as they became more adult, one that remains in use today. And their conclusions remain monumental:

“Thus, the main feature of the present hypothesis, which may be described as Stem Cell Renewal Theory, is the periodic appearance of a ‘stem cell’ which segregates itself from the spermatogonia dividing to produce spermatocytes, but which later divides to give rise to a new generation of spermatogonia and spermatocytes as well as to the ‘stem cell’ for the subsequent generation.”

The term “spermatogonia” is for an early cell in maturation whereas “spermatocyte” is a cell that is on its way to adulthood.

The key feature is that a stem cell would divide to make two cells — one being an identical stem cell, the other destined to become an adult cell. This is the fundamental basis of what a stem cell is defined as today.

Understanding bone marrow transplants

For Till and McCulloch in 1963, it was their experimental design that was key to their breakthrough.

They were testing the hypothesis that the success of bone marrow transplants was a consequence of a stem cell in the donor bone marrow that would give rise continuously to red blood cells, platelets and white blood cells.

If a host animal is irradiated severely, then the animal dies from being unable to make blood cells. Bone marrow transplantation cures the animal. After the transplant, colonies representing sites of formation of the blood cells can be readily seen in the spleen of the host animals.

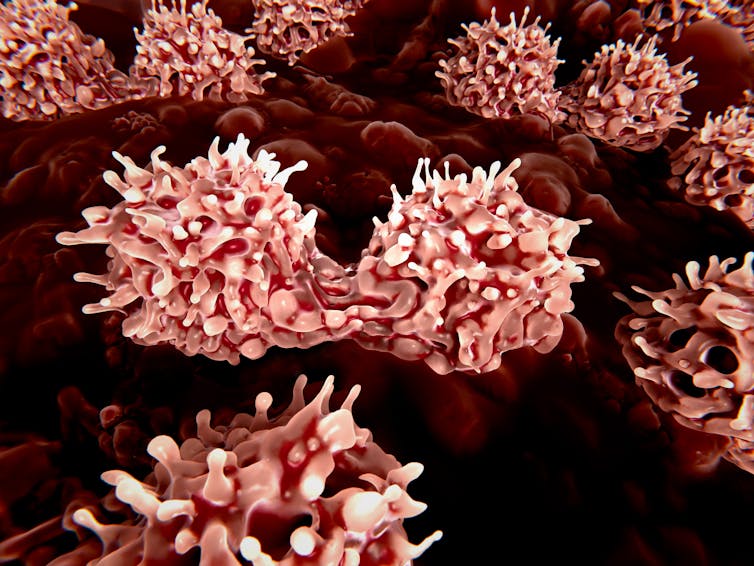

3-D rendering of stem cells in the bone marrow. (Shutterstock)

To test their hypothesis, Till and McCulloch used donor bone marrow cells that they could easily follow after transplantation. They generated these cells from mice given lower doses of radiation. This created a chromosomal abnormality in the cells that could be easily visualized by microscopy as the cells divided.

They transplanted these bone marrow cells into mice that had been severely radiated. Colonies making red blood cells, platelets and white blood cells were observed in the spleen of the recipient mice. Astonishingly in these colonies, blood cells were being formed, all with chromosomal abnormalities.

They were able to demonstrate that each colony arose from a single cell that today we call the stem cell. In the paper that reported their discovery, Till and McCulloch concluded: “The spleen colony procedure, may, therefore be regarded as an in vivo single cell technique….” They added “…it can be concluded that all the cells in these marked colonies were derived from a single cell in which a chromosome aberration was induced by radiation.”

How cancer can persist

Dick’s discovery of the cancer stem cell was based directly on the discovery of Till and McCulloch and followed a similar experimental strategy of using a mouse to test for the cancer stem cell. The challenge was enormous as he was studying leukemia in human beings.

Dick reasoned that if he could take bone marrow cells from patients with leukemia, he could test by transplantation into a mouse whether a human cancer stem cell could be deduced.

The strategy used a recipient mouse that was mutant and unable to make white blood cells, even normal ones. Dick then injected the leukemic cells he obtained from the bone marrow of patients into these mice. This led to an identical leukemia to that of humans in the mice.

The characteristics of the normal stem cell first discovered by Till and McCulloch were by now well understood. Dick then purified, from the human leukemia, the cells with the characteristics of what should have been the normal stem cell. This cell by itself when injected into the host mutant mice again recapitulated human leukemia in the mouse.

The breakthrough was based on the use of transplantation experiments similar to those of Till and McCulloch and based on their prior discovery.

Several different labs have reproduced this discovery of the cancer stem cell. This breakthrough provides an explanation as to why cancer can persist even after surgery or radiation treatment since the stem cell may not be located near the site of treatment.

On the shoulders of giants

Scientists are motivated by certainty that a genuine discovery will become part of our foundation of knowledge, enabling our understanding of life processes and helping to improve health and prevent disease. It is the legacy of a discovery that lives on.

Recognition for the creativity and beauty behind the scientific process that lead to genuine breakthroughs is sometimes overlooked.

Canada has made several such discoveries that are breakthroughs, especially the discovery of stem cells and the cancer stem cell. As stated by Newton: “If I have seen further it is by standing on ye sholders of Giants”.

The global giants in stem cell research are Canada’s Charles Leblond, Ernest McCulloch and James Till.

It is humans that choose to credit discoveries with awards such as the $3 million US Breakthrough Prize. Although several Canadian life scientists have made breakthroughs that are already rewarded by the legacy of their discoveries, a bonus of the actual Breakthrough Award may be worthy of consideration.

Could this year be any different?

John Bergeron gratefully acknowledges Kathleen Dickson as co-author.

John Bergeron, Emeritus Robert Reford Professor and Professor of Medicine at McGill, McGill University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.