There are a lot of “textbook” ideas that won’t survive coronavirus and this is one of them.

Courtesy of Joshua M Brown

Generations of investors had been taught that, in a bear market, the most gruesome casualties would be the highest-flying, most expensive stocks. This time, the experience has been the opposite. There are a lot of “textbook” ideas that won’t survive coronavirus and this is one of them.

Nothing has worked out better for investors than looking just like the index this year. The indexes have become dominated by the stocks most likely to survive and thrive in the pandemic. Seeing this coming in advance would have been nearly impossible, even if I had given you the exact date of the first White House press conference in advance this February – plus the infection rate – you could not have predicted the subsequent reaction in shares of Apple or Micron or Nvidia.

You didn’t need to see it coming. The S&P 500 index incorporated it, quickly, via the magic of market prices.

Here’s my colleague Ben Carlson on why the index approach worked so well recently:

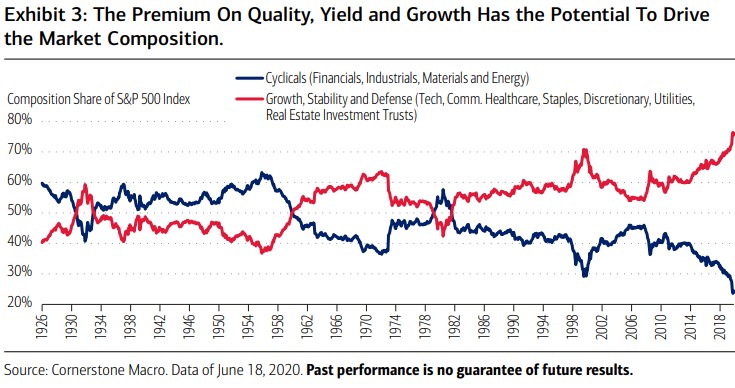

Cyclical stocks had their day in the 1940s, 1950s and early 1980s but the market is now dominated by growth, stability and defense stocks. Cyclicals are now at their lowest weighting in the index on record.

If you invested in a simple S&P 500 index fund you didn’t have to predict this sea change in advance. You didn’t have to make a bet on certain stocks, industries or sectors. The winner-takes-all nature of the S&P 500 itself did this for you.

The underperformance of cyclical stocks gets less relevant to the performance of the S&P 500 with every week of shrinking representation. It almost becomes a force that feeds upon itself.

Ben shares this breath-taking chart from Morgan Stanley:

There was a highly profitable period of time during the early part of the aught’s decade during which it paid off substantially if you built a portfolio that looked nothing like the indexes. The further away from index weights you were, the more toward small caps and value stocks, the smarter you looked after the bubble burst. In fact, many of the now-famous “names” in the hedge fund and mutual fund business had made their entire reputations during this period. They were out of the tech stock bubble and their results as that bubble fell by 90% looked incredible by contrast. Billions of dollars were redirected into their firms’ products and strategies. They stormed the podiums at investment conferences and their IR people told the story of this prescience among the family office and Wall Street wealth management hordes across the country.

That was then. It was a long time ago.

Almost none of those famed managers have been able to repeat that performance in the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis and its recovery period. And by now, their underperformance in recent years has become so substantial, that the benefit of having missed the tech wreck is no longer doing much for their historical performance versus the index. Which is partially contributing to the ongoing wave of retirement announcements.

In an era of fee compression, technological disruption and massive dispersion between winning growth stocks and losing value stocks, looking different from the S&P 500 has become almost completely intolerable for many asset managers. And while it’s always tempting to see these moments as a peak or a turning point, we’ve been living in this moment for almost seven years now. The moment itself has not only survived the onset of a global pandemic and recession, it’s actually fed upon it.

We’ve seen preexisting trends like ecommerce and cloud and virtual office adoption get pulled forward in increments of quarters and years. Amazon and Shopify and the ecommerce arms of Walmart and Target are now working on a penetration level that they may not have hit until 2022 or 2023. The adoption of online payments and billing have been shot out of a cannon into 2020, with an almost instantaneous cessation of the use of cash, in person, on the counter. Cash is dirty, cumbersome, slow, unaccountable and potentially hazardous to the carrier of too much of it. All of this was going to happen anyway. But Corporate America and Wall Street assumed it would play out over ten years, not ten weeks!

The virus and “work from home” orders accelerated all of this adoption and compressed its onset into a 90-day period that began with a jolt this March. The stock market has done its best to adjust to this overnight acceleration, and, of course, it has probably overshot it. That’s what stocks do.

Investors sitting in market-cap weighting index products didn’t have to see any of this coming. They didn’t even have to understand or accept it in real-time. All they had to do was accept the fact that there were forces in play they didn’t understand, and let the reality of this era gradually sink in for everyone else.

So when does the comeuppance happen for the crowd? When is the punishment meted out for the guys buying software and cloud stocks at 30 times sales? What is the catalyst that puts the top in for this sort of behavior, if it wasn’t the overnight loss of 22 million jobs and the threat of a million bankruptcies? Who will club the last buyer of Shopify over the head as an army of sellers takes control of the share price once and for all? What will embolden those sellers to believe there are no buyers left?

Previous versions of this cycle tell us two things: The first is that the top does not have to coincide with a readily identifiable, concurrent catalyst. Usually we have to wait until afterward to identify what it was.

The second thing we know is that a cataclysmic crash is not the only way investors get punished for overpaying. Sometimes it’s more like Chinese Water Torture.

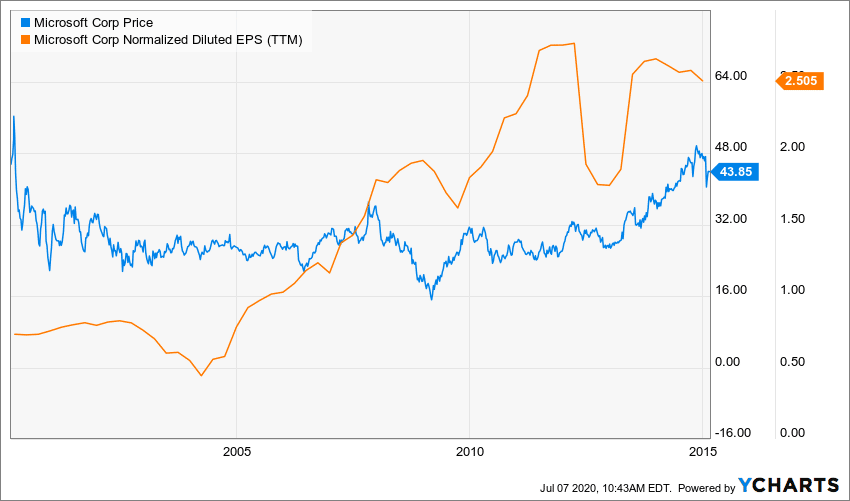

Microsoft’s earnings more tripled from 2000 through 2015 but its share price was stuck in neutral the entire time, because of its starting valuation. They call “correcting through time” rather than through price. Watch MSFT shareholders experience fifteen years of earnings growth (orange) with nothing to show for fifteen years of holding the stock as fully diluted EPS tripled:

Why did this horrible outcome befall shareholders of Microsoft who bought in circa the turn of the millennium? Well, they were paying 70 times trailing 12-months earnings for their favorite stock in January of 2000. Even Bill Gates was telling the press they were overpaying.

This could be the punishment rather than a 2000-esque 90% market meltdown. It will be more subtle and take years to be felt. That’s just one way things could play out. Indexers defaulting to market-cap weighting will feel the brunt of it, but very slowly.